Paul Rudolph’s organically curved floor plan for the dental office of Dr. Nathan Shore, in NYC—a work from the mid-1960’s. While Rudolph was known as a master of geometry and form (and their application to architecture, interiors, and furniture), this sinuous approach to planning was one to which he turned only occasionally. This “poche” version of the plan was used as a decorative graphic on the dental office receptionist station’s glass enclosure.

CREATION WITHIN A VARIETY OF SCALES AND TYPES: TRUE MASTERS WILL TAKE-ON ALL CHALLENGES

One of the signs of a master architect-designer is their ability to create interesting work at all scales. English architect Charles Ashbee, the Arts & Crafts era designer, is a strong example: designing everything from a typeface -to-furniture -to- houses -to- the renovation of a war-damaged city. His American contemporary, Bertram Goodhue, worked in a similarly broad range of scales: from his design of a typeface that is still in wide use (“Cheltenham”) -to- his Nebraska State Capitol, a building big enough to be seen from a distance of 20 miles.

Paul Rudolph indicated that he would be willing to take on even humble projects, and said:

“‘It makes no difference to me the size of the project. I’ve always said, ‘I would be happy to make a dog house for you, if you would let me make it a unique and very good dog house.’”

And, in fact, some famous architects have applied their architectural skills to dog house design: Frank Lloyd Wright (who called such a commission “an opportunity” in design), and Philip Johnson.

Young Jim Berger lived in a house designed by Frank Lloyd Wright for the Berger family in San Anselmo—and, at age 12, he asked Wright to design a doghouse for his pet labrador retriever. Wright sent a construction drawing and “Eddie’s House” was built. Here, in 2017, Mr. Berger is seen with a reconstruction of it, which was on display at the Wright-designed Marin County Civic Center.

Philp Johnson’s 1997 design: a “dog house” on the Glass House estate. According to the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s website: “This small structure was created by Johnson as a conceptual project for a classically-inspired tomb. However, when completed the small wooden object turned out to be just the right size for his and [David] Whitney’s new puppies to inhabit. . . .”

To our knowledge, Paul Rudolph never designed a dog house, but—across his half-century career, in which he engaged in hundreds of commissions—he was not above taking-on projects of a less-than-glamourous nature, or for clients with limited budgets.

One of the happy surprises we’ve encountered in the archives of the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation is an article from the Journal of the American Dental Association—and it’s about just such a project: Rudolph’s 1967 design for a dental office for Dr. Nathan Shore.

THE DENTIST GOES TO RUDOLPH

Rudolph’s client, Dr. Nathan Shore, was a dental pioneer in working on TMJ —and wrote this key book on the topic.

Dr. Nathan A. Shore (1914-1984), was a dental specialist and pioneer in correcting a jaw condition called temporomandibular joint syndrome—known more widely as TMJ—-a subject upon which he wrote numerous articles and a book (and for which he devised a test to determine whether the pain was medical or dental in origin.)

In he 1960’s, Dr. Shore asked Paul Rudolph to design his dental offices: they were to be located within a nearly windowless 1,830 square foot space on Central Park South, in the midtown section of Manhattan. Rudolph divided this area into 19 spaces:

four dental operatories

two hygienist operatories

two consultation rooms

an audiovisual room (for patient education)

a business office

a reception room

a kitchen for staff use

an X-ray room

two laboratories

two washrooms

all the above spaces connected by a continuous corridor

all remaining spaces, between the walls of the rooms, were utilized for storage.

Placing all these rooms and functions into the available square footage was an tour-de-force of space-planning efficiency. Although suite corridors were narrow, circular mirrors mounted on walls, and varied ceiling heights created an illusion of space.

Paul Rudolph’s floor plan for the Nathan Shore dental offices—probably the “presentation drawing” which was shown to the client (and/or other parties, such as the building management) to explain the design and obtain their approval. Each space in this quarter-inch scale plan is labeled; overall dimensions of the space are shown; and the entry is indicated by an arrow shown toward the bottom-center of the drawing.

A screen capture from the Museum of Modern Art’s website, showing a 1961 Jason Seley sculpture which is part of their collection: “Masculine Presence”. Like the sculpture that was in the Shore Dental office, this example is made from auto parts—Seley’s most frequent medium.

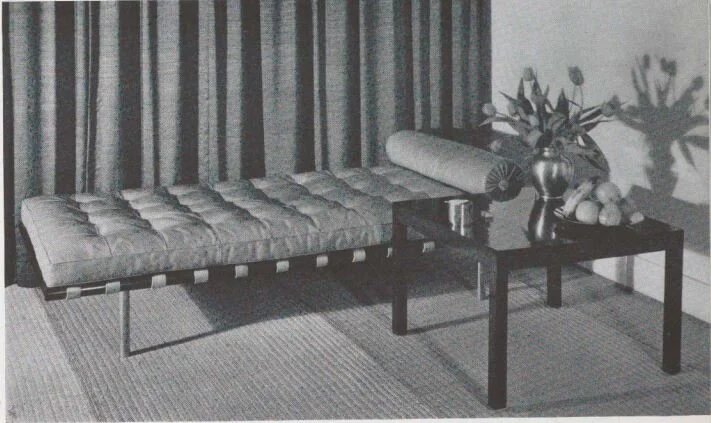

Furniture, in reception and some internal offices, included chairs by Charles and Ray Eames (from Herman Miller); and by Warren Platner (from Knoll International).

Desk lighting was provided by numerous “Lytegem” lamps (by Lightolier)—then and now, one of the most platonically pure lamp designs, made from a sphere and a cube—a composition strongly appealing to architects committed to the Modern aesthetic [This 1965 design, by Michael Lax, is in the collection of MoMA.]

The reception area contains a sculpture made of automobile hubcaps. It is by Jason Seley, a artist known for creating artworks from chromium steel automobile body parts.

The constructed design received coverage—perhaps the only article about it—in a 1971 issue of The Journal of the American Dental Association. The article, "Functional Design based on Pattern of Work in a Dental Suite", spoke of Rudolph’s design approach to meet the challenges involved in such a project, and included a description of the results, photos, and a floor plan. The article’s author, Eileen Farrell, had been an editorial supervisor at the American Dental Association, and some of her observations included:

"Dentistry in the round is one way to describe the unique dental suite designed for Dr. Nathan Allen Shore by architect Paul Rudolph of Yale. . . .The circular motif is repeated in various ways that add to the total effect. Lighting in the operatories, for instance, is diffused from a circular well in the ceiling across which the dental light slides on a track integrated with the ceiling diffusor. A curved Plexiglass screen divides the business office from the reception room, making each space seem larger. A circular rendition of aspects of the temporomandibular joint decorates the door leading to the operatories.”

"Besides creating an illusion of space, the design aims at quiet and a sense of privacy. To this end, circulation of patients and staff is kept to a minimum, and although there are eight staff members and a steady stream of patients, the suite never seems to be crowded. One reason is that the movement of traffic is in the round rather than back and forth. . . .When a patient arrives for his appointment, the secretary opens the door by remote control and admits him to the reception area."

"Doctor Shore finds that his staff is happy in the well-designed quarters. . . .Functional design, he says, seems well suited to a most progressive profession."

Above are small screen-captures of the pages of the article about the Rudolph-designed Nathan Shore dental office. At the lower-right is a slightly enlarged portion of one page, showing the reception area—and, at its right side, one can see that the suite’s floor plan has been incorporated into the reception desk’s window, as an intriguing ornamental pattern. The full article can be accessed through the JADA website, here.

RUDOLPH AND CURVILNEAR DESIGN

The work of Paul Rudolph presents difficulties for historians—at least for the ones who are uncomfortable with the great range of forms in his designs, and the multiple approaches Rudolph used when answering hundreds of architectural challenges. Attempts to pigeonhole a great creative force like Rudolph are doomed to futility—but some observations on his formal vocabulary are worthwhile, like our analysis of his use of crystalline shapes at Burroughs Wellcome.

But what about Rudolph’s use of curved forms? Rudolph could hardly be said to be afraid of curves: they show-up early in his practice: most notably in the Healy “Cocoon” house of 1950. But projects where “free form” or “biomorphic” curvilinear elements and planning dominate are not all-that-frequent in his career. Some notable exceptions are his sculptural handling of concrete in his Temple Street Parking Garage and the forms and spaces of the Boston Government Service Center. But even in Rudolph’s Endo Laboratories—one of his finest projects from the beginning of the 1960’s, which is well-known for its curved elements—or his Daiei Headquarters Building in Japan, most of the curves are carefully controlled portions of circles or ellipses. Thus when we do encounter designs in which Rudolph uses free and energetic organic lines (as in Dr. Shore’s offices), there is good reason to give such projects extra focus—and even to celebrate this branch of Rudolph’s creativity.

In the spirit of our start of this article—pointing-out that design masters can productively focus on projects of all scales—we end with an example at the smaller end of the range of objects which Paul Rudolph designed: a desk for Endo Laboratories. Thoughtfully designed for efficient function, and carefully drawn, detailed and specified (as the drawing shows)—it also fully embraces “free form” curvilinear design.

An “executive desk”, designed by Paul Rudolph for the offices of Endo Laboratories, his 1960 project in Garden City.

IMAGE CREDITS

NOTES:

The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation gratefully thanks all the individuals and organizations whose images are used in this non-profit scholarly and educational project.

The credits are shown when known to us, and are to the best of our knowledge, but the origin and connected rights of many images (especially vintage photos and other vintage materials) are often difficult determine. In all cases the materials are used in-good faith, and in fair use, in our non-profit, scholarly, and educational efforts. If any use, credits, or rights need to be amended or changed, please let us know.

When/If Wikimedia Commons links are provided, they are linked to the information page for that particular image. Information about the rights for the use of each of those images, as well as technical information on the images, can be found on those individual pages.

CREDITS:

Floor plans of the Nathan A. Shore dental office (both “poche” and linework versions), and the drawing of the desk for Endo Laboratories: © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation; Frank Lloyd Wright-designed doghouse: photo courtesy of Marin County Civic Center, as shown on the city’s website; Philip Johnson-designed doghouse: photo by and courtesy of Sean Sheer of Urban Dog; Jason Seley sculpture, within the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City: screen capture from a portion of the MoMA web page devoted to that sculpture; JADA article on the Nathan A. Shore dental office: screen captures from the 1971 issue, Volume 83, Issue 1; Cover of Dr. Shore’s book: from the Amazon page devoted to that book.

![Philp Johnson’s 1997 design: a “dog house” on the Glass House estate. According to the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s website: “This small structure was created by Johnson as a conceptual project for a classically-inspired tomb. However, when completed the small wooden object turned out to be just the right size for his and [David] Whitney’s new puppies to inhabit. . . .”](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a75ee0949fc2bc37b3ffb97/1631026468289-HZPCE6M866A7YQ4ZBZP2/Urban+dog+johnson+doghouse.jpg)