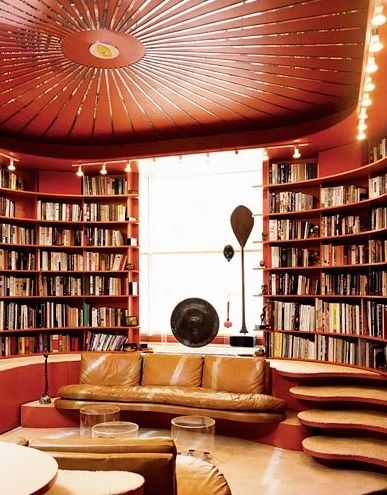

The cover of FDR: FLORIDA DESIGN REVIEW, showing the living room of Paul Rudolph’s multi-level apartment in New York City. That issue’s coverage was the most comprehensive (and best photographed) article to ever appear about this most personal of Rudolph’s architectural works. The magazine is now out-of-print, but copies are available through the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation’s “Shop” page.

FDR: FLORIDA DESIGN REVIEW was a magazine devoted to architecture, interior design, and the allied arts. Its large format and high-quality photography allowed readers to have a rich and immersive experience of the buildings and spaces upon which they focused.

The magazine didn’t just look at design in Florida. They showed projects in a variety of locations—and in their issue number two (2007), they featured Paul Rudolph’s own home in New York City.

We’re frequently asked about Rudolph’s famous apartment—a design which he experimented with and refined and revised over many years. It contained some of his most spectacular residential spaces, and was certainly his most “personal” project. It was a “quadruplex”—a magnificent four-story penthouse apartment, facing New York City’s East River. He used it as a “laboratory” for exploring ways to shape space and create dynamic experiences.

While Rudolph’s apartment was widely published, that issue of Florida Design Review is important, because it has an 18 page article on the quadruplex: the most comprehensive coverage ever published of this richly conceived & fascinating residence.

The author, Richard Geary, is himself a distinguished designer. The photographs in the article (often printed full-page) are by Ed Chappell. Also included in the article is a design sketch by Rudolph, as well as two of his famous section-perspective drawings of this multi-level apartment.

The bad news is that Florida Design Review is now out-of-print, and copies can be hard to find. But—

But the good news is that the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation has a number of copies of this issue available. It can be purchased through the PRHF’s website, on our “Shop” page (along with a number of other interesting Paul Rudolph publications and items.)