Steel, glass, and multi-level spaces: the Modulightor showcases Paul Rudolph's multilayered legacy. Not a museum, but a living organism that continues to engage with the city and the present.

Architectural Digest - Italia

Olivia Fincato - February 27, 2026

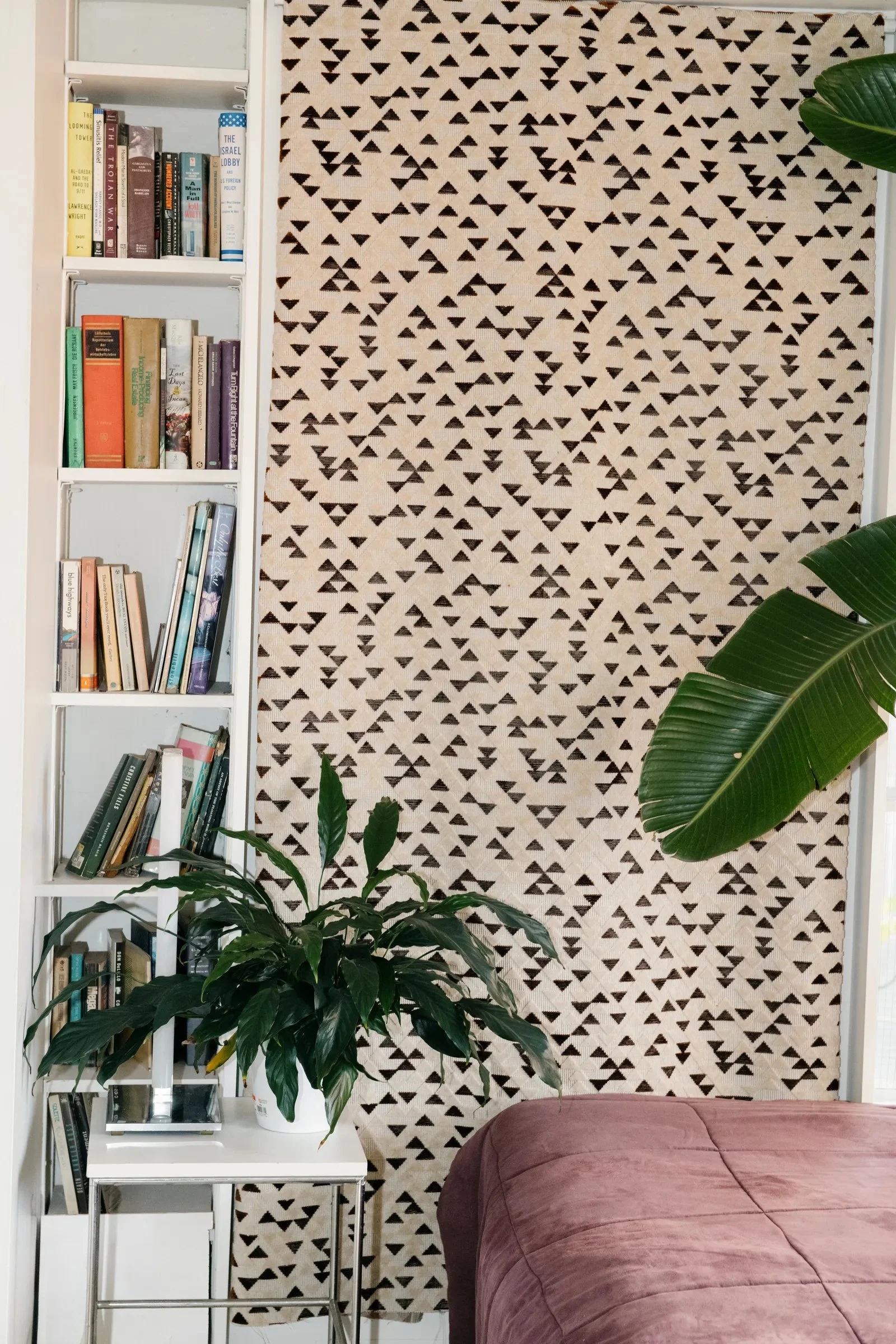

The living area of the apartment inside the Paul Rudolph Institute for Modern Architecture at Modulightor. Dedar updated the apartment's textiles. Photo by Adrianna Glaviano.

In the Modulightor Building in Manhattan, where the legacy of architect Paul Rudolph lives on.

Paul Rudolph Institute for Modern Architecture at Modulightor. Photo by Adrianna Glaviano.

“I keep Paul Rudolph's legacy alive by treating the Modulightor building as he did: an open, active, and always teaching living design laboratory.” These are the words of Kelvin Dickinson, New York architect and current president and CEO of the Paul Rudolph Institute for Modern Architecture, the institution that preserves and animates the last building designed by architect Paul Rudolph in Manhattan.

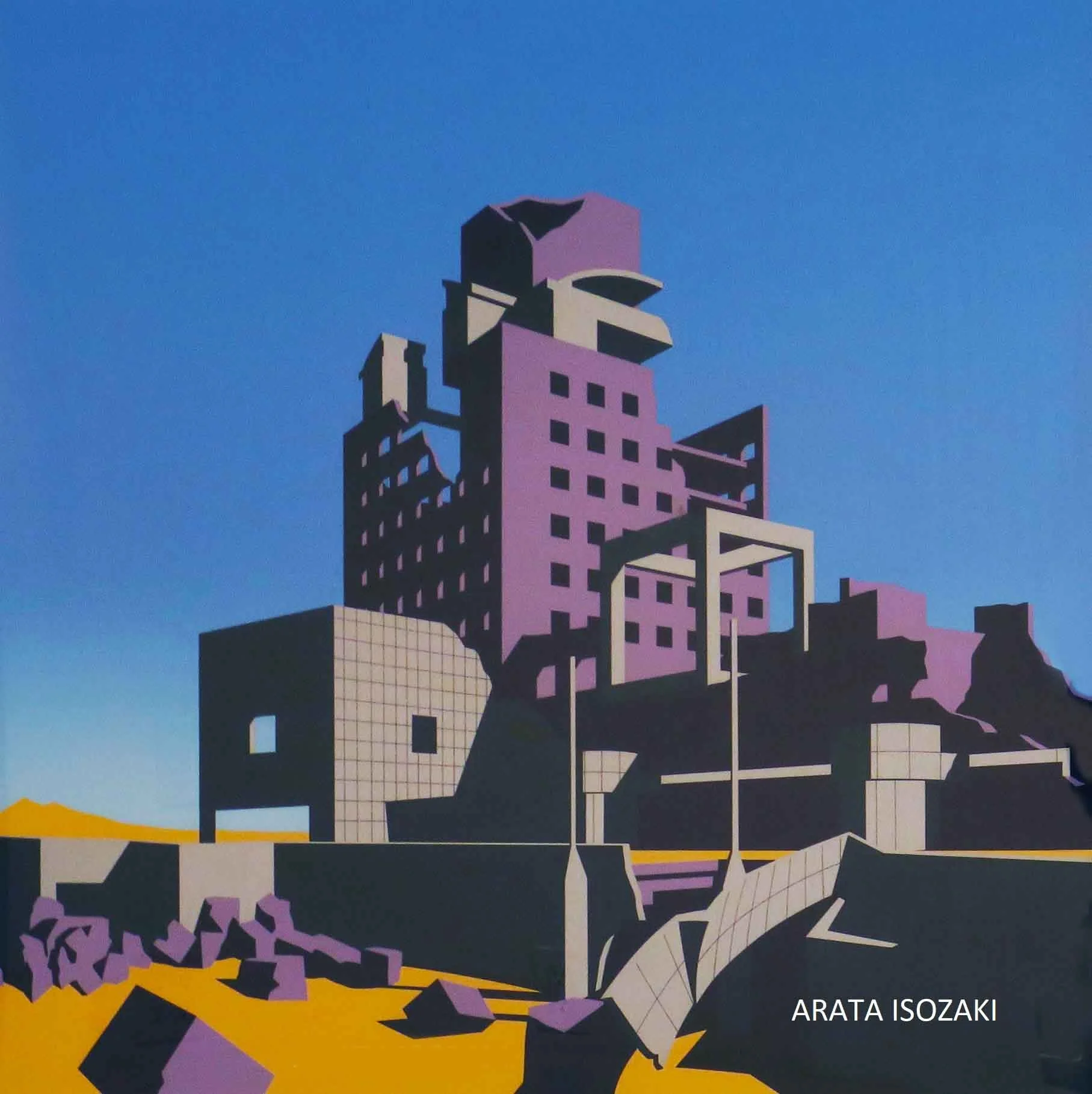

The Modulightor building, an active laboratory

Paul Rudolph isn't a household name like masters Ludwig Mies van der Rohe or Louis Kahn. Yet, in the 1960s, he was one of the central figures in American architecture. Born in 1918 and educated at Harvard under Walter Gropius, Paul Rudolph was among the most radical exponents of American modernism, known for his plastic, layered Brutalism, capable of transforming concrete into vibrant surfaces. At forty, he became dean of the Yale School of Architecture. Among his best-known works: the Yale Art & Architecture Building (now Paul Rudolph Hall), the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth campus, and the Boston Government Service Center. Then the climate changed. Many buildings were criticized, others demolished. His legacy remained fragile.

Multipurpose structure

The living area of the apartment inside the Paul Rudolph Institute for Modern Architecture at Modulightor. Dedar updated the apartment's textiles. Photo by Adrianna Glaviano.

This Manhattan building on 58th Street, however, is different. The Modulightor Building, designed in the architect's final decade, has received double protection: the façade was designated a New York City Landmark in December 2023 by the Landmarks Preservation Commission, and in May 2025, the interior duplex also received Interior Landmark status. This is a rare recognition for a 1980s building. The building was originally designed as a multipurpose facility: a production studio and showroom for the Modulightor lighting company, founded by Paul Rudolph in 1976 with his life and work partner Ernst Wagner; the second-floor studio and apartments above.

Interior of the Modulightor Building. Photo by Kate Owen.

“The Modulightor embodies Paul Rudolph's modernist vision, transforming a narrow New York lot into a complex environment and a conscious contribution to the urban fabric,” explains Dickinson. “The steel and glass façade with concrete panels hints at the internal complexity. Inside, the duplex is conceived as a sequence articulated across multiple levels, a composition of interconnected spaces, where variations in height and width generate continuous spatial movement and multiple viewpoints. The staircase also reinforces this idea: the cantilevered, 'suspended' steps function as sculptural elements that transform as one moves through the space.”

A habitable musical work

Interiors of the Paul Rudolph Institute for Modern Architecture at Modulightor. Dedar updated the textiles in the apartment. Photo by Kate Owen.

The building is not a simple superposition of planes, but a carefully orchestrated, habitable modern work. “Rudolph conceived of space as an experience,” Dickinson continues. “A dynamic, psychologically engaging sequence, never static.” He adds that complexity “was likened to music, a Bach fugue, where richness and layering are not a problem to be simplified, but the very substance of the composition.” The cantilevered, suspended steps transform the staircase into a sculptural element. Natural light activates surfaces and voids from ever-changing angles. “The space changes throughout the day,” Dickinson says. “Twenty years later, I still find myself taking out my phone to photograph it. It excites me as much as the first time. It always manages to surprise me.”

Paul Rudolph Institute for Modern Architecture at Modulightor. Photo by Kate Owen.

The simplicity of the materials is also surprising: steel and glass on the outside, painted plywood and plasterboard on the inside. “Many associate Rudolph with Brutalist concrete. But a good architect uses all materials. A good project doesn't require marble or expensive ornamental finishes.” There's one point that, for Dickinson, sums up the essence of the space: “A ledge on the north side of the upper floor. From there, you can see the suspended stairs and galleries diagonally. It's a view that encompasses everything.”

Interiors of the Paul Rudolph Institute for Modern Architecture at Modulightor. Photo by Adrianna Glaviano

Climbing plants are an integral part

The flower boxes are inserted into the recesses of the facade and, inside, overlook the voids between one level and another. Photo by Adrianna Glaviano.

But there's also a less obvious, often overlooked detail. “The planters,” he says. They're set into the recesses of the façade and, inside, overlook the voids between one level and the next. Rudolph imagined climbing plants trailing down from there, making the interior feel almost like an open-air space. “Nature is an integral part of the project.” It's not a decorative gesture. It's a way to blur the lines between structure and environment, between artificial and organic. Even in a building made of steel, glass, and industrial panels, the architecture is never closed in on itself.

Active space, in dialogue with the present

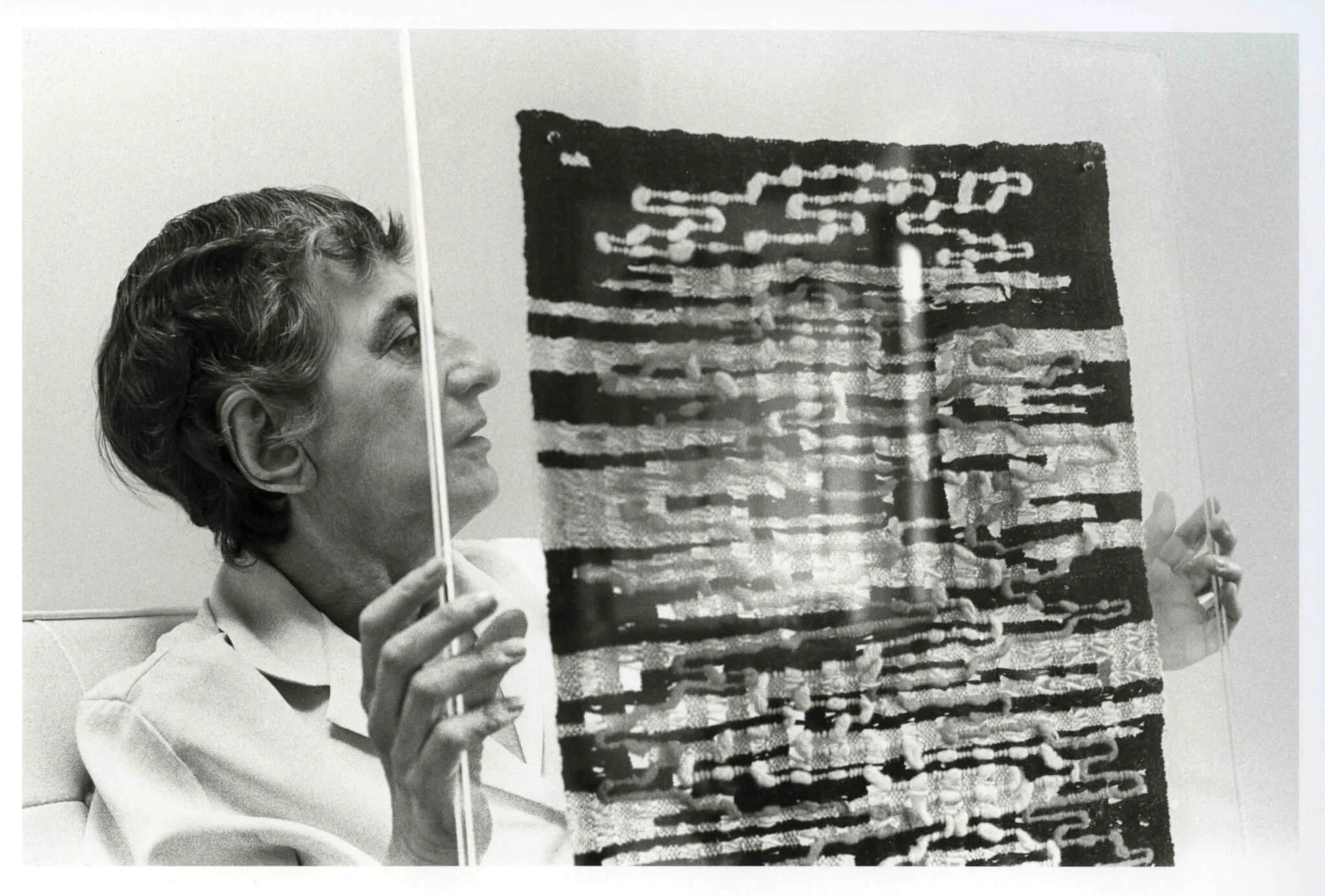

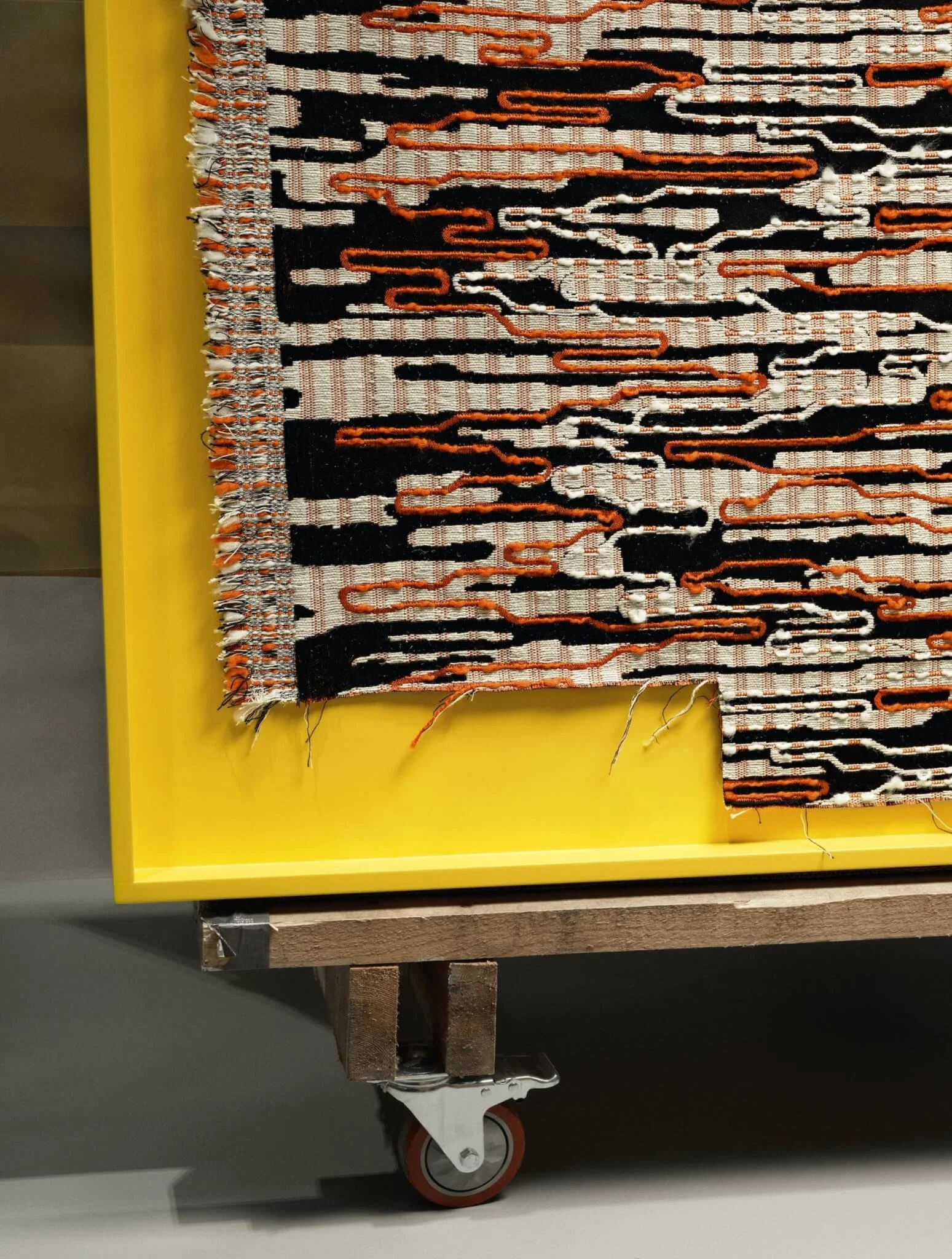

The Paul Rudolph Institute for Modern Architecture at Modulightor is a multifunctional active space. The Weaving Anni Albers exhibition recently concluded, and Dedar's intervention remains permanently integrated into the space. Photo by Adrianna Glaviano.

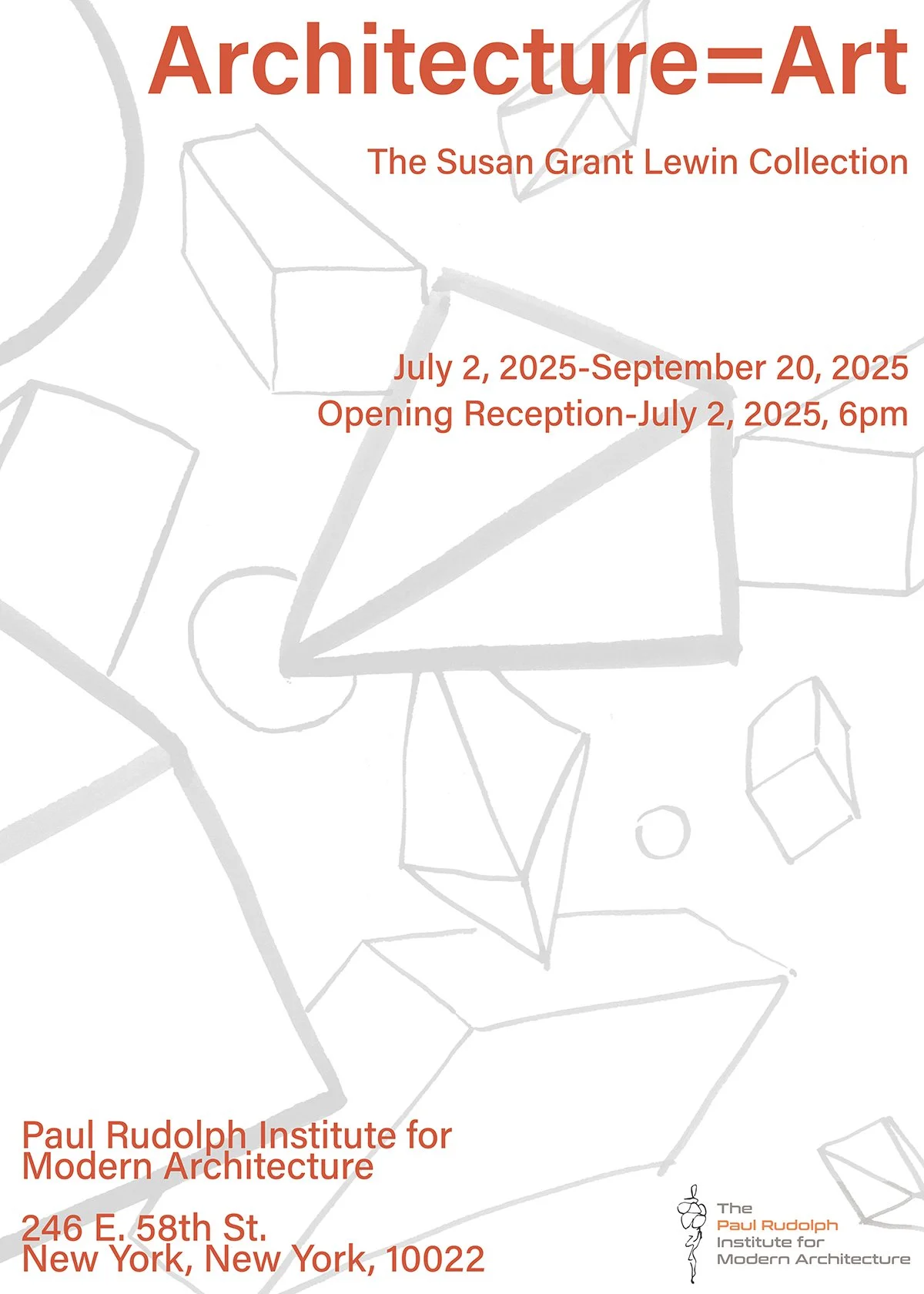

After Rudolph's death in 1997, Ernst Wagner lived in the duplex for over twenty-five years, opening it to the public in 2005. Upon his passing in December 2024, the building passed to the Paul Rudolph Institute. The goal is not to turn it into a museum, but to activate it. “We're preserving the original spatial concept,” Dickinson explains, “but keeping it current with open houses, talks, tours, and exhibitions that place Rudolph in dialogue with the present.”

Dedar textiles amplify the modernism of interiors

The collaboration with Dedar fits into this context. The textile house has permanently updated the apartment's textiles with a selection designed to engage with the luminous geometry of the architecture. Conceived in conjunction with the recent exhibition Weaving Anni Albers, the project remains permanently integrated into the space. Through material, rhythm, and structure, in which Albers's Bauhaus roots intertwine with those of the building, textures and colors have been reintroduced, amplifying the modernist clarity of the interiors.

Dedar has permanently updated the apartment's textiles, a collaboration that began in conjunction with the recent exhibition "Weaving Anni Albers." Albers' Bauhaus roots intertwine with those of the building, and textures and colors amplify the interior's modernist clarity. Photo by Adrianna Glaviano.

Inventive, experiential, engaging modernism

Interior of the Modulightor Building. Photo by Kate Owen.

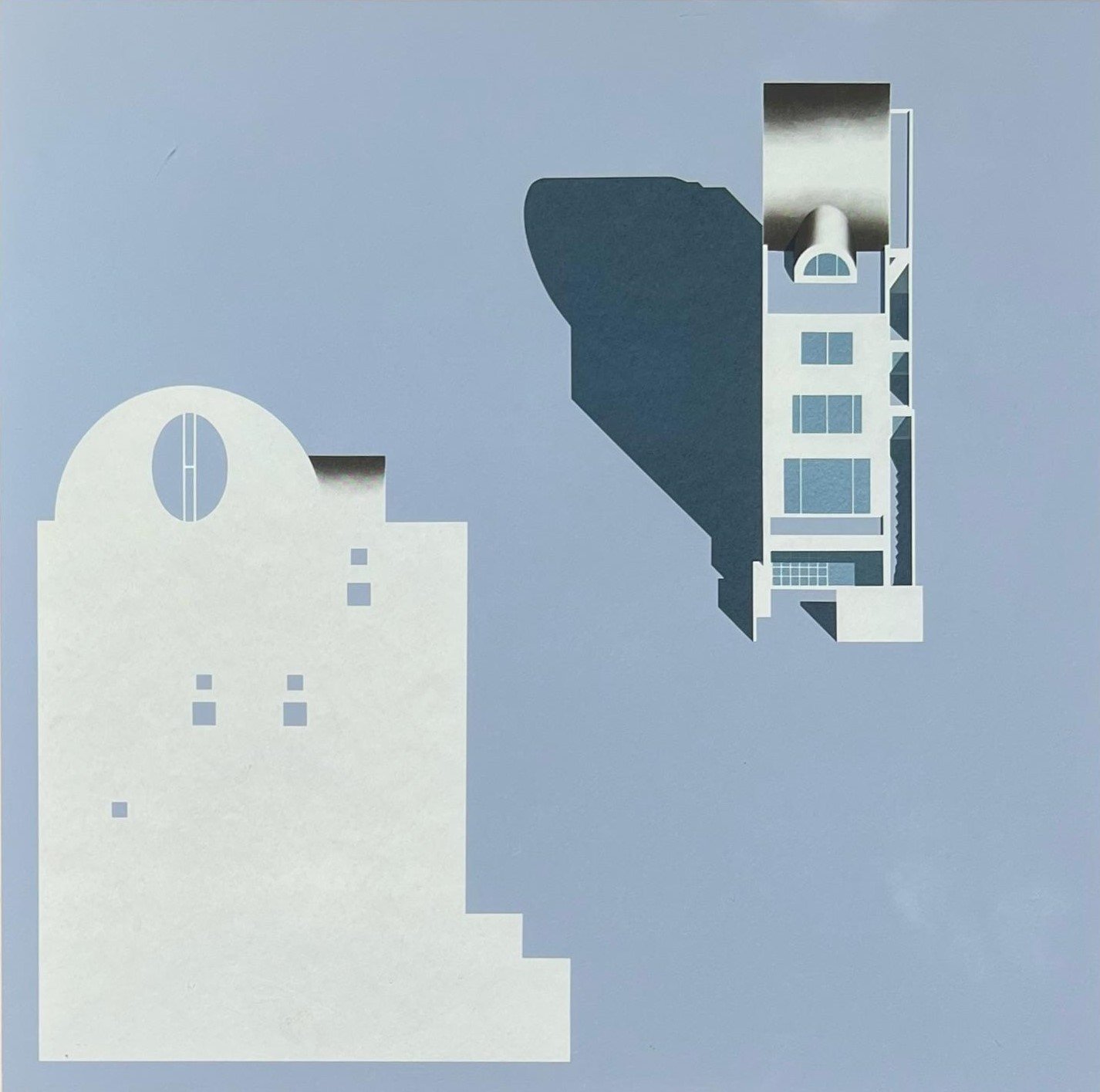

“We use the building as Rudolph envisioned it: as a special environment and a contribution to the city,” Dickinson concludes. “Paul Rudolph's architecture is still relevant because it proposes a version of Modernism that is inventive, experiential, and forward-thinking, not simply minimalist. First, he conceives space as an experience: interconnected sequences on multiple levels that make architecture dynamic, psychologically engaging, never static. Second, he anticipates the current interest in modular and economical systems. His complex compositions arise from simple forms, shifted, lifted, and repeated, consistent with his idea that architects should 'speak the language of modularity.' Finally, he is materially and technically inventive in a way that still feels contemporary today. His legacy continues through the architects he trained and mentored, such as Norman Foster and Richard Rogers.”

The bedroom inside the duplex at the Modulightor Building. Photo by Adrianna Glaviano.

In a time when many late twentieth-century buildings remain vulnerable, the Modulightor Building survives. Not as a static sanctuary, but as a working space where modern architecture continues to be experienced, discussed, and reinterpreted.

The Modulightor Building on 58th Street. The facade was designated a New York City Landmark in December 2023 by the Landmarks Preservation Commission, and the interior duplex also received Interior Landmark status in May 2025. Photo by Joe Polowczuk.

Go to the original article here.