When a pastor learned his childhood home might undergo a glow-up, he saw his beloved Brooklyn further receding — and took to a different kind of pulpit.

New York Times

Ginia Bellafante - January 15, 2026

The home in question, a modernist townhouse in Brooklyn Heights designed by Mary and Joseph Merz. Credit...James Estrin/The New York Times

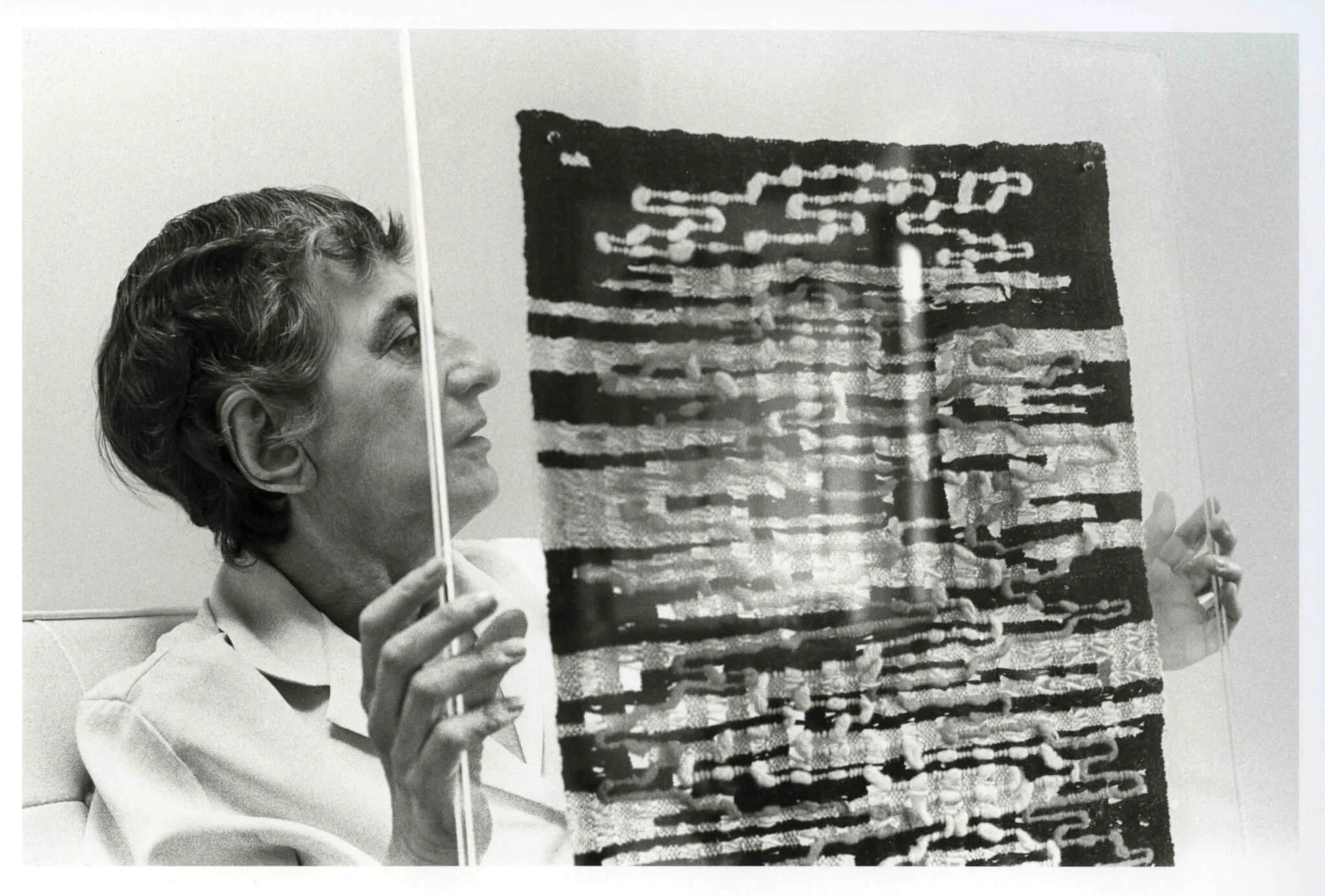

Late one night in November, John Merz got some news about his childhood home that left him unsettled. A friend had texted a link to an article on a site devoted to New York real estate, reporting that the house, a midcentury building designed by Merz’s parents, the celebrated architects Mary and Joseph Merz, was about to undergo a potentially dubious alteration.

It could seem like a small thing. John Merz, 60, has had many chapters since he last lived in the house almost 40 years ago — as a college student; a cabinet maker; a graduate of Yale Divinity School at 38; and, most recently, as the rector of the Episcopal Church of the Ascension in Brooklyn. More than an ordinary fondness for his old house, he felt an abiding commitment to honor the imprint his late parents had left on the fringes of Brooklyn Heights.

Brought up as Catholics, Mary and Joseph Merz made architecture their religion — the interplay of line, form and context the prevailing theology. “I knew enough about Louis Sullivan when I was 12 years old that I thought he was related to us,” John joked recently.

In the bedroom of the church rectory that night last fall, he clicked on the link and stared at a rendering of the proposed project. He was jolted toward distaste for what he described as a “birthday cake” — a square glass and steel addition, 14 feet wide and nine feet high, that would sit in the middle of the roof. Given the location of the house on a corner, the structure would be all too visible from the street. In Merz’s view, this would amount to “a civic cost to accommodate a private want.”

At that point, the identity of the new owners was unknown to him. They had acquired the house through a limited liability corporation, a common tool of the rich to ensure anonymity in real estate transactions. Through Department of Buildings filings and the Brooklyn grapevine, Merz learned that his childhood home now belonged to Andrew Beck and his partner, who had paid $10.6 million for it in 2024. Beck had been a managing director at the global investment firm DE Shaw before leaving Wall Street a decade ago.

Reverend John Merz at the Episcopal Church of the Ascension in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. Credit...James Estrin/The New York Times

Change in Brooklyn Heights, the city’s first historic district, is not easily negotiated. All but the most minor repairs to building facades are contingent on the approval of the Landmarks Preservation Commission. In recent years, though, the commission has faced criticism for acquiescing to the sorts of projects it might have previously rejected, and Merz could not assume it would veto Beck’s proposal. As he read about it, he decided he did not have the bandwidth to mount an opposition.

After waking up at 5:30 the next morning, he changed his mind. He made calls and had the recipients of those calls make more calls. Architects and preservationists joined his cause. He enlisted his sister Katie Merz, a public artist. She and her boyfriend posted signs around the Heights, equipped with a QR code linking to a petition that asked the community to “protect” the house. The effort gained more than 775 signatures.

This was how Beck learned about the hostility bubbling up around his proposal. “No one contacted us with concerns before going public with them,” he told me.

Merz, at the same time, wondered why Beck had not reached out to him. The previous owners of the townhouse, he said, had solicited feedback from the family about their renovation.

Beck had hired the architect Basil Walter to design the glass structure and roof garden. Walter’s firm, in turn, worked with a consultancy that advises on projects that go before the landmarks commission. Those involved with the plan said they considered it modest, unobtrusive.

“We were shocked by the campaign against our experts’ proposal,” Beck said.

When I asked Roberta Brandes Gratz, a landmarks commission appointee under Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg, what she thought of the plan, she said she found it “atrocious.”

Mary and Joseph Merz had built the house and two others like it in the early 1960s, on Willow Place, an intimate street one block long distinguished by a row of Greek Revival houses from the 1830s on one end and Gothic Revivals built later on the other.

A 1965 shot of the townhouse at night. Credit...Merz Family

The Merz houses, in a style often described as Brutalist, were praised in the design world from the outset, even among preservationists. It was their impression that new construction in the neighborhood ought to represent the best of contemporary architecture, rather than replicate 19th-century style and risk Disneyfication.

In 1969, the American Institute of Architects honored the Merz houses for their sensitivity to location. Over the decades, professors from Harvard, Columbia and Pratt Institute brought students to Willow Place to show them what the successful integration of a new stylistic language could look like within a traditional idiom.

To John Merz, Beck’s rooftop plan threatened his parents’ careful dovetailing of past and present. “I felt the voice of my parents and all those students groaning — a big historical groaning of Why?” he said.

At a meeting in early November, a subcommittee of the local community board approved Beck’s proposal, if certain modifications were made. Some in the neighborhood were indifferent to all the debate feeling that the houses were so ugly it didn’t matter what went up above them. The landmarks commission could take these opinions into account at a hearing scheduled for Nov. 25.

To comply with protocol, a full-size mock-up of the structure was up on the roof. Merz wanted a closer look. Theoretically, he could have gotten a glimpse from the roof next door, but the owner of that house lived in Sweden, and Merz hadn’t spoken with him in 48 years.

The mock-up of the proposed addition. Credit...Merz Family

His sister Katie mentioned the problem to a cinematographer friend, who offered the use of his DJI Mavic Air 2, a drone equipped with a camera. It flew above Willow Place for 15 minutes, delivering precise images. Whether this exercise was legal was unclear.

On a frigid morning in early December, Merz, who lives with his wife and two children a few miles up the Brooklyn waterfront, in Greenpoint, returned to his old neighborhood. We stood across the street from the three houses his parents had built on the contiguous lots they acquired in 1961 for $11,000.

Merz took a laser pointer from his pocket and directed it at the roof of the third house to reveal a glass rooftop addition, built 20 years ago. He did not find this problematic, because it was set far back enough that only a lip of about 12 inches was visible from the street. The landmarks commission had rejected an initial plan that would have made it more prominent. The visibility standard is taken very seriously, according to Brandes Gratz, who served on the commission at the time. “There are lots of landmarks issues that are debatable,” she said. “This is not one of them.”

The owner of that house was Martin Hale, who had bought it in 2013 with the appreciation of someone who had studied architectural history at Yale. Hale had inveighed against Beck’s rooftop proposal even before Merz’s campaign was underway. He had sent the landmarks commission a Google deck, 11 slides long, in which he argued that the structure would break the block’s skyline. He also referred to an instance in 1978 when the commission had rejected a similar proposal for the second Merz house.

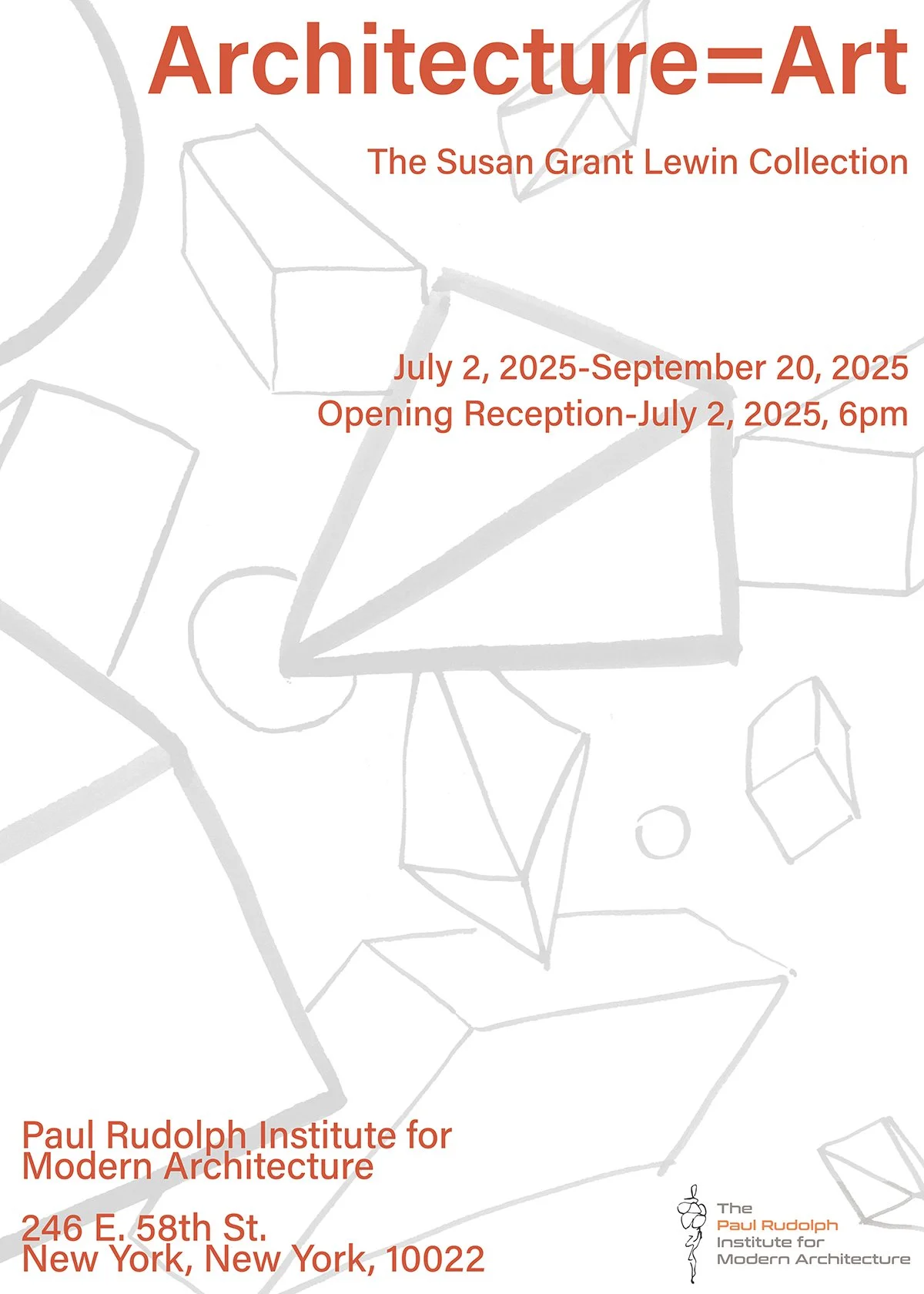

Katie Merz’s petition asked to uphold those precedents. As it circulated, the commission received 29 letters of opposition. One letter came from Kelvin Dickinson, the president of the Paul Rudolph Institute for Modern Architecture, who pointed out that the materials for the proposed addition, “weathered steel with a galvanized steel guardrail,” were incompatible with the building’s wood and concrete.

A vintage photograph of the architects Mary and Joseph Merz. Credit...Merz Family

Andrew Dolkart, a professor of historic preservation at Columbia, was among several experts who volunteered to speak at the hearing. “Each of those houses is very pure in its geometry,” he told me. “Putting something above them, well, why not just pop out a window?” Here, he was providing an example of the unthinkable.

What struck him, in particular, was that the Merzes built the three houses at a time when there were no rules to constrain them. They are “incredibly pioneering examples of contextual design before there was even a landmarks commission,” he said. The couple could have built higher, or done nearly anything. But they held back.

To the Merzes, Modernism was as much a call to social advancement as it was a means of aesthetic expression, and for that reason John Merz saw the houses both as monuments to a restrained use of proportion and the progressive values his parents shared. The Merzes could take months, even years, to settle on the right end table, their son told me. But their unyielding approach to design was countered by an expansive view of community, and they brought people into their orbit eclectically as they settled into a neighborhood in transition.

The area was rough by any measure. A drummer named Jimmy Rios got to know Joe Merz on a basketball court, one block over, on Columbia Place, where he still lives. In the 1970s, gangs ran wild, Rios said, pulling antennas off car hoods for street fights. The Merzes responded to the disorder by planting trees. They also designed a playground for the end of the block. When two bear sculptures were placed in it, Rios and his friends named them Joe and Mary.

Then and now: Construction begins on the corner townhouse more than 60 years ago above; and below, the same spot today. Credit...Merz Family

One of the Merz houses was built for Leonard Garment, a jazz saxophonist who played with Billie Holiday and eventually became Richard Nixon’s lawyer. An evening on the block might begin with cocktails at the Merzes’ and round out with dessert and more drinks at the Garment place, where Daniel Patrick Moynihan was a frequent guest.

Or it could take shape with Joe setting out a folding chair and a meal for Butchie White, who hung out across the street when he was not in prison. In the early ’70s, White was sentenced for attempting to set fire to a townhouse behind the Merzes’ by throwing a lit refrigerator box into a window because a friend of his had been evicted.

The owner of the house nearly lost to arson was another noted architect, Wids DeLaCour, a friend of the Merzes. In those days, DeLaCour told me, the city allowed owners to evict tenants with little difficulty, presuming you were moving into a building yourself. If Beck’s rooftop addition was going to exact “a civic cost,” as Merz had phrased it, the vision imposed by the gentrifiers of the 1960s and ’70s had levied their own. As well intentioned as the Merzes’ arboreal initiative had been, it annoyed kids on the block because it interfered with playing stickball, Rios told me.

Still, John Merz could not shake the sense that what was happening now was a defamation of his parents’ legacy. His parents understood their domestic space as a shared civic commodity. When they found out a dockworker who moonlit for them as a handyman was sleeping in his car, Katie Merz recalled, they invited him to live with them for a while and taught him how to read and write. In the front of their house, the Merzes enclosed their plantings with a ledge built at seat height, to invite congregation. The glass rooftop structure would not simply be an addition to a house, Merz maintained, but “a wholesale subtraction of a longstanding and valued architectural good.”

Mary and Joseph Merz with John. Credit...Merz Family

As a cleric who founded a mobile food network, North Brooklyn Angels, to deliver meals to people in need, Merz was all too aware that a dispute concerning a modification to a one-percenter’s townhouse might seem comically trivial. “The dissonance, I get it,” he said. “I can see people reading about all this and thinking, Who cares?” Still, to his mind, the proposed expansion spoke to something resonant, the erasure of “a coherent architectural statement for no compelling public reason.”

Contests between cultural privilege and enormous financial advantage often resolve with moneyed interests winning. The narrative turns in Brooklyn Heights were not so easily predicted.

In the Netflix version of the conflict, the owner of the Merz house would be a rapacious jerk. But Andrew Beck, known as Trey, had left finance to concentrate on philanthropy, working with organizations focused on child poverty. As one former colleague put it, “He was the only guy on Wall Street I had nothing bad to say about.”

A few days before the scheduled landmarks hearing, something unexpected happened: Beck pulled his application. “Trey is a very sensitive person and never wanted to offend anyone,” his architect, Basil Walter, said.

A rear view of the townhouse on a corner of Willow Place. Credit...Merz Family

What drove the antipathy seemed to extend, at least in part, beyond the matter of building height and perhaps even beyond a collective disgust over perceived entitlement, wealth disparity and the self-siloing of the very rich. It suggested a weariness with the chaos and desecration that mark so much of our common experience and a hope to gain some feeling of control from a winning campaign against a single luxury asset.

Is that how Merz felt? When renovations face backlash in New York, homeowners often remount their efforts with revised plans. Merz said that if that happened, he would involve himself again.

After Beck backed down, he received a text from a friend that read, “Victory.” Merz wasn’t so sure. “I know enough about church history,” he said, “to know that there is no such thing.”

Go to the original article here.