Architects Newspaper

Ilana Amselem - November 10, 2025

At the Paul Rudolph Institute, Weaving Anni Albers, reimagines the textile pioneer’s Bauhaus-era weavings within Rudolph’s modular masterpiece. (Adrianna Glaviano)

At the Paul Rudolph Institute for Modern Architecture in New York, Weaving Anni Albers, presented by Italian textile house Dedar in collaboration with The Josef & Anni Albers Foundation, reimagines the textile pioneer’s Bauhaus-era weavings within Rudolph’s modular masterpiece. Draped across steel frames in vivid primary hues, the jacquard fabrics transform the late modernist townhouse into a habitable loom where fabric and structure intertwine.

Curated by Stephanie Barth and Carina Frey, and spatially conceived by Akari Endo-Gaut, the exhibition works to align Anni Albers’s rigorous approach to weaving with Rudolph’s architectural rhythm. Both shared Bauhaus roots. Albers, who studied at the school in the 1920s, carried its experimental spirit into her weaving practice. Rudolph, trained at Harvard under Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius, inherited the school’s emphasis on structure and craft.

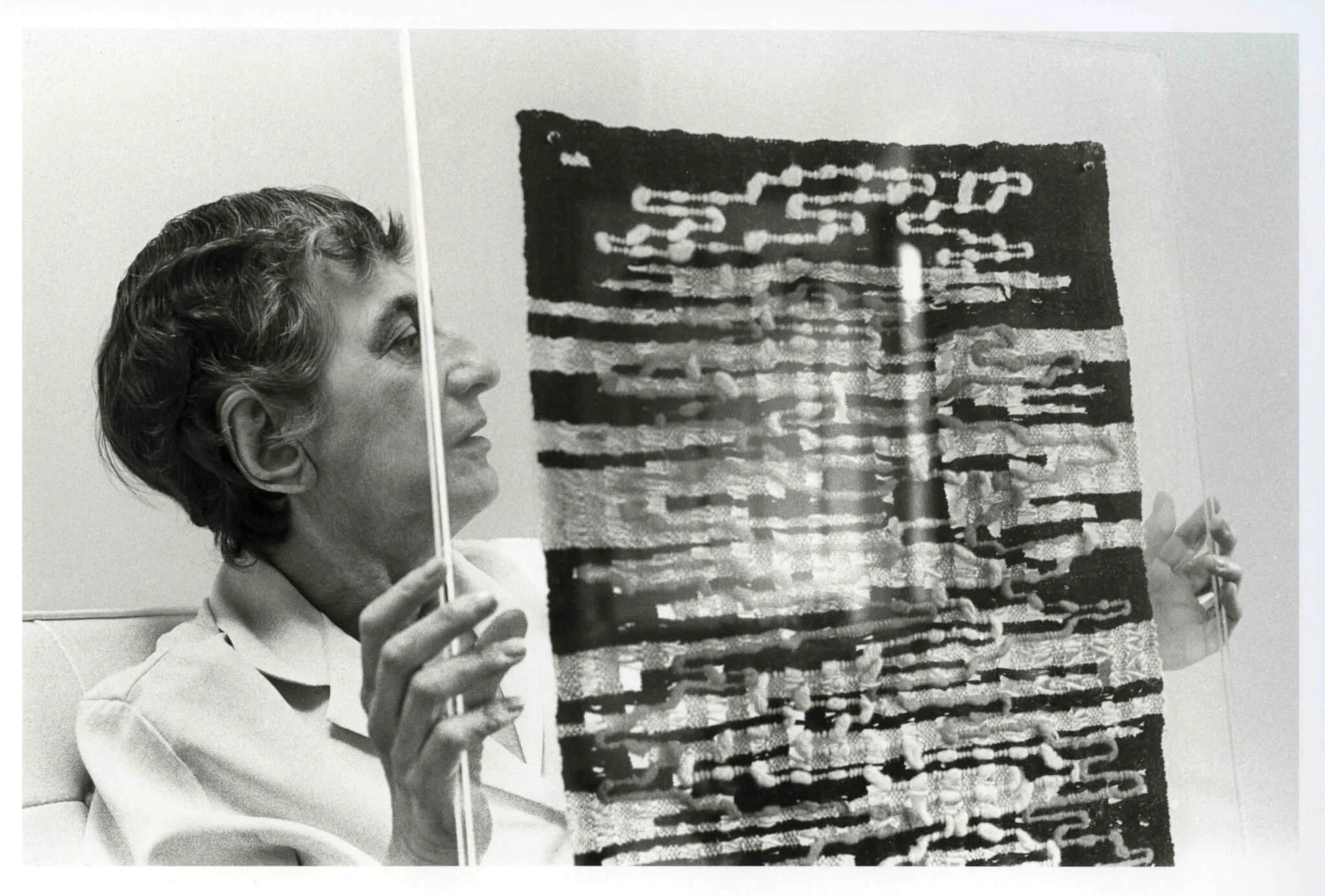

Anni Albers holding her weaving Under Way, New Haven, Connecticut, 1965 (John T. Hill/Courtesy the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation)

In the exhibition, Rudolph’s white lattice of stairs, mezzanines, and light wells becomes a scaffold for Albers’s tactile compositions. Endo-Gaut’s scenography treats color and structure as warp and weft. The Modulightor’s rectilinear volumes are recast as a loom through which the fabrics are threaded. Panels of intricate patterning create immersive corridors of texture.

“I envisioned visitors immersing themselves fully in the exhibition,” said Endo-Gaut. “I want them to see the colors, the intricate textures, and to experience not only the visual beauty but also the complex processes behind each textile.”

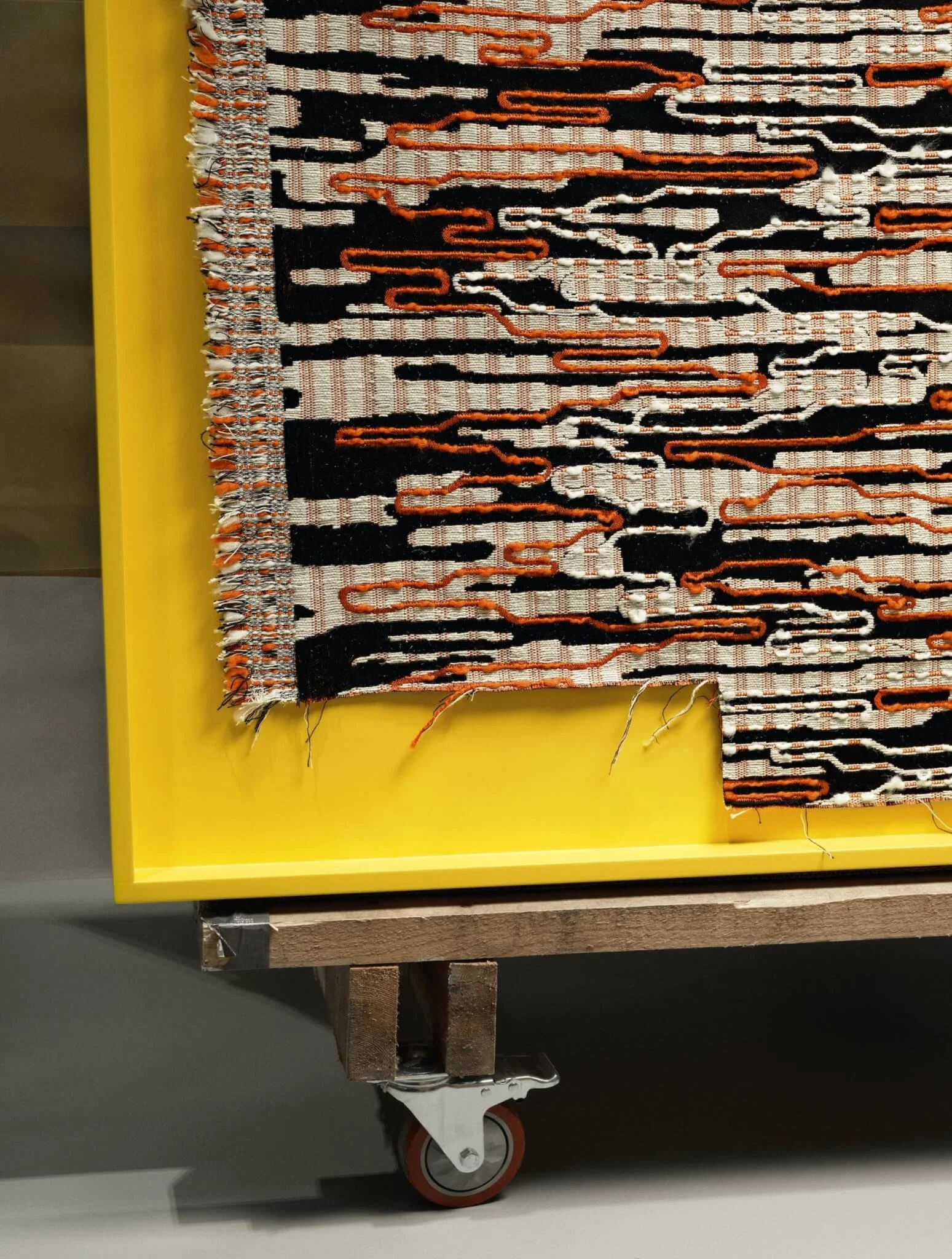

Under Way (1963) and En Route (1961–67), revive Albers’s meditations on the wandering line, a motif derived from Paul Klee’s invitation to “take a line for a walk.” (Courtesy the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation)

The five featured jacquards reinterpret Albers’s designs from 1936 to 1974 into contemporary production through Dedar’s technical mastery. Ancient Writing (1936) renders Zapotec-inspired geometries into ivory and charcoal, nodding to Albers’s fascination with Mesoamerican weaving traditions. Untitled (1948) translates the flicker of a nocturnal cityscape into a complex of wool, jute, and silk, while Drawing XVI (B) (1974) animates a field of irregular triangles in plush velvet. Other fabrics, like Under Way (1963) and En Route (1961–67), revive Albers’s meditations on the wandering line, a motif derived from Paul Klee’s invitation to “take a line for a walk.”

Weaving Anni Albers is open through November 11, 2025. The exhibition includes sound design by Paolo Tocci and a short film directed by Alessandro Del Vigna. (Adrianna Glaviano)

Both Albers and Rudolph sought to expand modernism’s vocabulary, she through the discipline of the loom, he through the rigor of structure. In Weaving Anni Albers, visitors pass from intimate domestic nooks to soaring double-height spaces. The experience is tactile and architectural, a meditation on the interdependence of surface and form.

In Weaving Anni Albers, visitors pass from intimate domestic nooks to soaring double-height spaces. (Adrianna Glaviano)

Weaving Anni Albers is on view through November 11. The exhibition includes sound design by Paolo Tocci and a short film directed by Alessandro Del Vigna.

Go to the original article here.