A home in Chester, NY that the owners claim was designed by Paul Rudolph. Image from a previous listing on Weichert Realtors.

When you represent the estate of an architect who has designed residential properties, you eventually receive word that they are going to be sold. At that point, in steps a real estate agent with the marketing vocabulary and poetic license to find a new owner.

As Christine Bartsch writes in her blog Writing Creative Real Estate Listing Descriptions: 3 Pro Tips (and a Warning!), “The better your listing description is, the better your chances are that buyers will come see your home in person. And the more showings you have, the higher your odds are to get multiple offers.”

It can sometimes be hard to find a new owner for a Rudolph-designed home. They can be of a certain age that they seem too small for today’s buyers (like the Cerritto Residence) or in a location that is no longer remote and in danger of being demolished for a bigger house (like the Walker Guest House) or they can be in a style that can make them hard to love (like the Micheels Residence).

In some cases the owners reach out to the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation and we work with them to find a new owner who will preserve the property. We list these properties on our website with instructions here.

As we state in our mission statement, one of our goals is to help provide connections between sellers of Rudolph properties with preservation-minded buyers and design-sensitive real estate professionals. In order to ensure the properties are preserved, it is important they are owned and maintained.

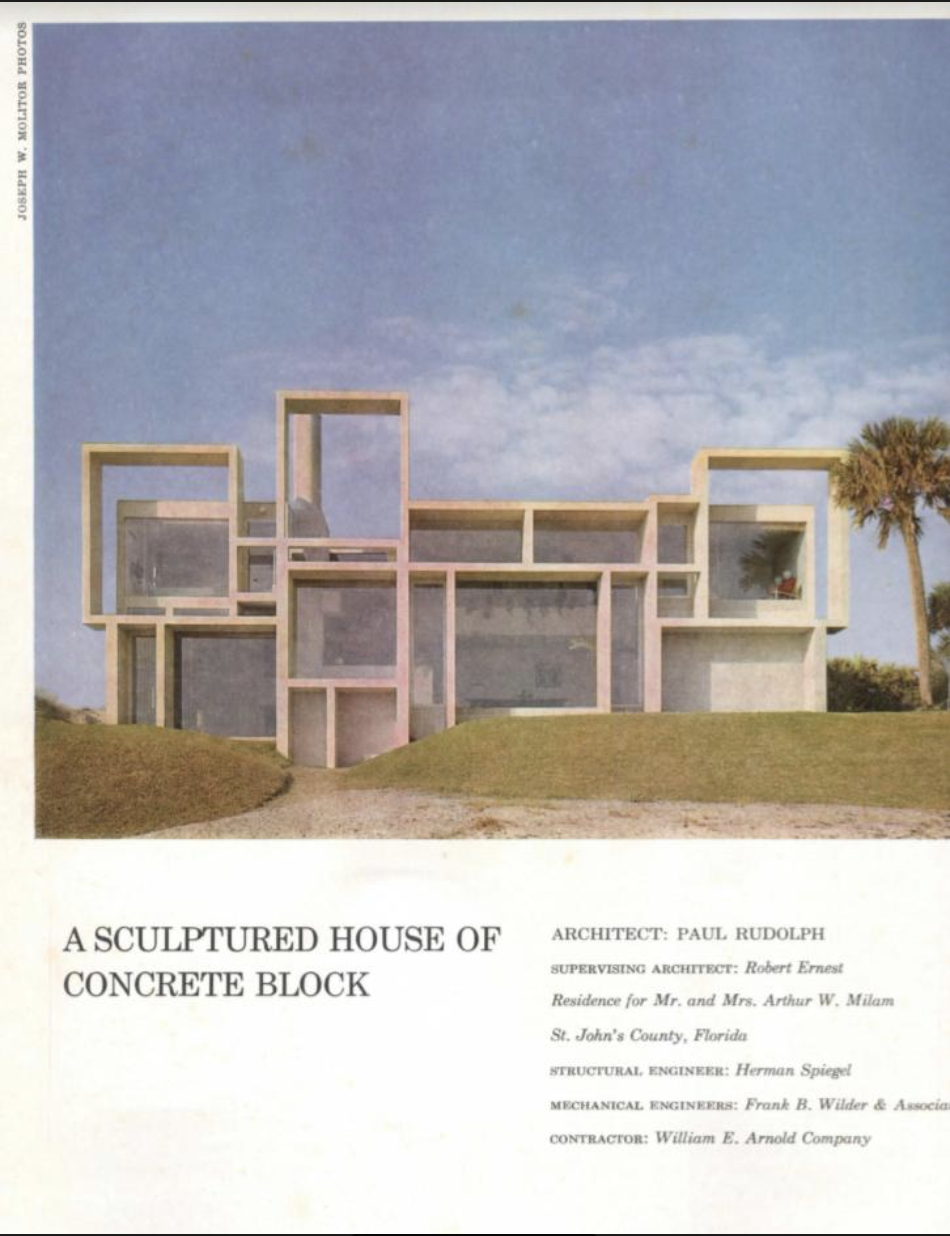

So its interesting that - while its already challenging to preserve original Rudolph designs - we come across properties that claim they are Rudolph designs when there is no evidence that they are.

Note: The following homes are not included in Rudolph’s project list and we have no evidence (in either drawings, photographs or written communication) that they are Rudolph designs. We are happy to update our archives if the owners contact us and can provide supporting documentation.

Let’s take a look at three of these homes:

904 Virginia Drive in Sarasota, Florida

The original house in 2007

The new house in 2020

According to the property’s listing:

This entertainer's dream home is located in the heart of Sarasota's Cultural District. This home was designed by renowned architects Ralph Twitchell and Paul Rudolph in 1940 with construction being completed in 1941. The home was remodeled and expanded in 2009, and refreshed in 2019. The design is a perfect blend of contemporary and mid-century modern.

As soon as we read the listing (sent from a Rudolph fan) we knew the Rudolph reference was mistaken because he joined Twitchell’s office in the Spring of 1941 - the same year construction was completed.

We reached out to several friends in Florida and learned the original address is indeed a Twitchell design, known as the ‘Second Lu Andrews residence’. Pictures of the home appear in John Howey’s 1997 book The Sarasota School of Architecture, 1941-1966.

We were provided a note by a previous owner in the 1990’s that explains a short history of the home. Below is an excerpt:

“There was a small piece in our paper yesterday in the real estate section about the Lu Andrew home in Tahiti Park. I was moved to give a brief history of her second home built in 1939, which my husband and I owned about six years ago. Both homes were built by her boss Ralph Twitchell.

When Pat and I started looking to buy our first home we were living on Hickory street and had both been living here and there in the IBSS neighborhood for years. It was our hope to find a house in the area, and we spent a year looking.

Walking our dogs we came upon 904 Virginia Drive, a for sale sign had just been erected and we immediately went back home to call our realtor to inquire about this charming modern house. We set up an appointment for the very next day, the price was a bit out of our range, but with the idea of negotiating we remained positive.

Meeting the realtor at 904 we knew right away that the outside of the property was a dream, and once the door opened we knew instantly that we had finally found our home. It was small, 900 square feet, perfect for two. It was important for us that the house we bought wasn't entirely bastardized.

Walking into 904 we were delighted by the original integrity, design and layout. Putting an offer in quickly, and dealing with owners that loved the house and yard, it was a given that it would all work out.

Once we occupied the Twitchell house we started to research it's previous owners and history. In the hopes of meeting it's original owner we went to see if Lu Andrews was home at her Tahiti Park address.

Arriving there, we knew from the looks of the house that it hadn't been lived in for quite some time. One of her neighbors saw us and we all started talking and she told us that Lu's son had put her into a nursing home just a few months ago. She knew a lot about the history and about Lu, and was kind enough to let us know where Lu was now living. We called the nursing home and made an appointment to meet with her.

We learned that Ralph built the home for Lu and her son, that Lu slept in the living room on built-in day beds (no longer there) that her son slept in the back bedroom and the front room was to rent out to someone so that it was affordable for Lu. Times ware tough in Sarasota in the 40's, the building boom declined rapidly and when the war broke out work was hard to get. Being a single parent with a son to raise, Lu moved to Washington DC to work as a secretary. She had lived in 904 for a short time, never to return. she moved back to Sarasota after the war and the Tahiti Park house was built for her by Ralph, but the materials used were more humble as the economy here was still tight. She was a dear lady, and her memory faded back and forth, but we were still able to extract this brief history.

Once our children arrived the house was becoming quite small, so we investigated adding on and hired the architect John Howey. We felt John would be perfect as he had just published a book on the Sarasota School of Architecture. Plans were drawn and during the process my neighbor across the street had decided to sell his home, and it was offered to us. Economically it was a wise decision, building the addition was expensive in comparison. We would be going from 900 s.f. into 2000 s.f. without the headache, but with the loss of our sweet Twitchell home.

Sometimes we make decisions with the hopes the what we decide will stay the same, unfortunately two years ago 904 was forever changed.

The beautiful 100 year old river cypress torn away from the walls - paneled throughout the ceilings and walls - piled high into dumpsters. When living at 904 while reading in bed my eyes could not help but to always delight in the beauty of the cypress grain, every bit worthy, of it's title, River Tide, as the grain looks like the water moving along the shore. As if the cypress tree is so ingrained into the life of the water from which it is born.

Twitchell often left a whimsical signature in the homes he built, stars cut out from the cypress, and the cut out itself, neatly imposed near entryways. As the demolition continued at 904, Pat was able to salvage the star paneling and many paneling boards.

On the back of some of the boards was a stamp from the lumber mill from which the cypress originated. In 1922 Cummer Sons Cypress Company was built on 100 acres in Pasco County, in the town of Lacoochee, Florida. The town of Lacoochee thrived for nearly 40 years, where Cummer Sons Cypress, a giant in the logging and lumber industry, made their last stand near the Withlacoochee river. It closed in 1959, and with its demise the town fell into hard times, as the mill was the main employer, providing jobs and housing mostly for African Americans.

I still dream about 904, mostly that I have forgotten a treasure, tucked away in the beautiful memory of a cypress tree.”

The home was modernized in the 2000’s and then later sold to a new owner who demolished 95% of the house and rebuilt it. As our source in Florida told us, “Twitchell at 904 Virginia Drive is long gone.”

On a side note - a wonderful SketchUp model of Lu Andrews’ 3rd house at Tahiti Park referenced in the note above can be found here.

1212 East Sierra Way in Palm Springs, California

A photograph of 1212 East Sierra Way from the property’s listing on Zillow.

The AirBNB listing for the 4,100 s.f. property states:

This iconic mid-century multi-level home in the prestigious Indian Canyons neighborhood was designed by renowned architect Paul Rudolph. Casa Colibri is a sprawling property with expansive rooms and an abundance of floor-to-ceiling windows that shed light on the spectacular, mid-century interior.

In this case, we were alerted by Docomomo - a non-profit organization dedicated to the documentation and conservation of buildings, sites and neighborhoods of the modern movement - asking for confirmation. The listing says the exact location will be provided after booking. A little digging and we discovered a similar listing for ‘Casa Colibri’ on Vrbo which also states, “this iconic mid-century multi-level home in the prestigious Indian Canyons neighborhood was designed by renowned architect Paul Rudolph.”

What caught our eye was the Vrbo listing headline - “3 bedroom 5 bath mid-century 4100 sq ft home featured in modernism week tours.” When members of the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation were in Palm Springs for Modernism Week in 2019 to see the Walker Guest House replica we had no idea we were only a 6 minute drive away. No one we spoke to mentioned a Rudolph-designed home was in town, and information about Rudolph at the replica’s installation made no reference to it.

A public records search of Palm Springs (along with a little flying around via Google Earth) and we learned that Casa Colibri is located at 1212 East Sierra Way. According to the property records, the residence was built in 1977. We also found a Zillow listing for a previous sale by Douglas Elliman in 2017 that states:

A house of pure architecture and one of Indian Canyon's most dramatic houses. The different levels recall the work of modernist architect Paul Rudolph and are part of what makes the sight lines so interesting. Extensively renovated by Solterra Construction in 2008 this home has comfortable yet contemporary style and lots of architectural drama.

Within a few years a house that ‘recalls’ Paul Rudolph has become ‘designed’ by him.

19 Greentree Lane in Chester, New York

Photo from the Property Description Report from the Orange County, NY Municipal website

The 7,202 sqft home - which sold for $285,000 in 1995 and then $238,000 in 1999 - jumped 1,034% in price to $2,700,000 in 2014. According to public property records, the home was originally built in 1986 and last modified in 2000-2001. The additions include a 240 s.f. carport, 650 s.f. attached garage and 80 s.f. covered porch. No date is available when the heliport was added on the property.

The residence was listed and delisted several times since 2013 and marketing mentions Paul Rudolph although you might miss it based on the spelling:

“The Hudson Villa is named after its historic origin. Created by the renowned architect Paul Rudolf, the estate is a masterpiece of design and craftsmanship featuring a private white-sand beach and a resort-like setting less than an hour away from New York City.” - Hudson Valley Style Magazine, 07/09/2020

On its own website, the property description states:

“Designed by the renowned American architect Paul Rudolph, the home pays homage to the lodge tradition - precise craftsmanship is evident in architectural accents including cathedral ceilings, light-flooding skylights, and warm stone elements. Security and privacy are front of mind in the design, layout, and features of the property.”

We encourage you to visit the website and judge Rudolph’s participation for yourself based upon the pictures of the home’s interior.

Or, you can check this listing from the Off The Mrkt blog in September 2018:

Reality TV personality and mentor on Scared Straight and MAURY, Dave Vitalli, is selling an aspen style safe house in Chester, New York for $3,088,000.

This safe house located at 19 Greentree Lane was originally built by Paul Rudolph, a renowned architect, in 1986. Rudolph spared no expense when it came to making sure the house would withstand the threats of the world outside.

The safe house is built of thick slabs of concrete and reinforced steel to help maintain the structure just in case something were to happen. It also has generators, wells, and septic systems in place to allow for comfortable off the grid living. This property has also been previously used as a retreat for diplomats, celebrities, and dignitaries through the years.

The site includes a link to Rudolph’s wikipedia page, because they wouldn’t be able to find a link for the home in our project archives.

Its also interesting to note that the home’s location - Chester, NY - is located in Orange County. Orange County is best known for several Rudolph-related preservation controversies including the destruction of the John W. Chorley Elementary school in Middletown and the partial destruction and insensitive addition to the Orange County Government Center. Could the controversy and Rudolph’s name in the local paper have inspired the marketing connection?

The USModernist organization - which follows and promotes the preservation of modernist homes - says the house was “for sale 2014-2018, advertised as a Paul Rudolph design, based on a claim by the owner. We found no evidence to support that claim whatsoever, and the owner declined to produce any.”

USModernist contacted the property’s real estate agent in 2017, who could not produce any documentation but that Rudolph’s authorship is something ‘the family told them.’ The agent also said the owners commissioned Rudolph to do the renovation. However, they bought the house in 1999 after Paul Rudolph had passed away in 1997.

After speaking with us, USModernist informed the sales agent and asked that the record be corrected. Instead, the house was delisted only to return yet again as a Rudolph in several relistings with different agents ever since.

Rudolph comes up a few times in the history of this property - either ‘sparing no expense’ in 1986 or renovating the property in 1999 from the afterlife. We note with irony that the renamed ‘Hudson Villa’ is trademarked on the listing’s current website, while taking liberty with the mention of Rudolph’s involvement in the ‘trademark’ design.

Why Now?

Several sales of Rudolph properties have been in the news lately, so we aren’t surprised that Rudolph’s name is being used as a marketing tool.

In 2019, two original Rudolph properties were sold. The 1952 Walker Guest House in Sanibel, Florida was sold at auction by Southebys-New York in December for $750,000 and, with auction house fees, the total came to $920,000. As we reported earlier this month, it is in the process of being moved to a location in California.

The other sale was Rudolph’s 1986 Triestman Residence which went through a subsequent interior modification by the new owner.

In 2020, Rudolph’s 1949 Bennett Residence was sold for $395,500 after being listed for just 3 days. We learned that the new owner purchased it sight unseen for the full asking price - even in the middle of a pandemic.

This year also saw the sale of the Walker Guest House Replica that was on display during Palm Springs Modernism Week (a short drive from the would-be Rudolph) by Heritage Auctions. Bidding began at $10,000 - the budget for the original home when it was first built.

So when we find sellers using Rudolph’s name as a way to get more attention, we take it as a sign of success in our efforts to keep Paul Rudolph’s work in the public’s consciousness.

None of this is meant to make a value judgement about the homes mentioned above, just that they are not Paul Rudolph designs. As is the case with art or architecture, its ‘buyer beware’ and in some cases definitely not ‘you get what you pay for.’