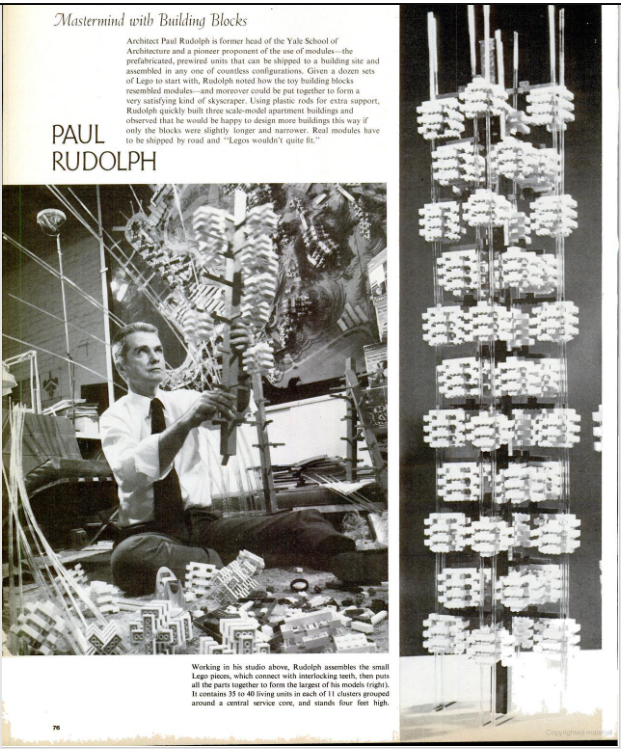

Paul Rudolph’s representation of the human figure used as the logo for the Paul Rudolph Institute for Modern Architecture.

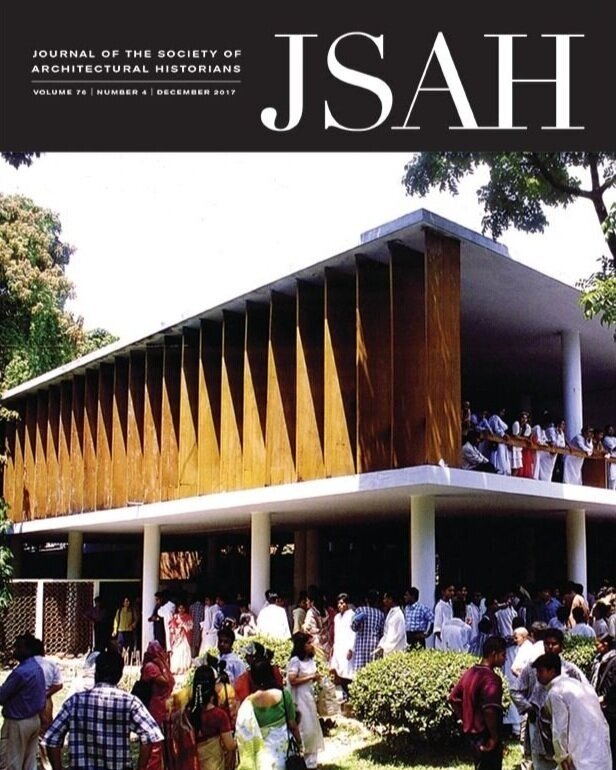

The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation and the Paul Rudolph Estate are excited to announce the launch of the Paul Rudolph Institute for Modern Architecture.

The Paul Rudolph Institute for Modern Architecture (PRIMA) will replace the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation and expand its mission to provide outreach and information to educators, students, design professionals and the broader public interested in learning about the design principles of modern architecture exemplified in Paul Rudolph’s architectural work and teachings.

“Principles are principles. Principles don’t change. Styles change; attitudes change. Things are in a constant state of flux. The only grasp one can have on the profession is to get a handle on great principles.” - Paul Rudolph

Rudolph referred to these principles as the ‘DNA’ of architecture and they include issues of site, function, space, structure/materials, scale and style (referred to as the spirit of the times). These principles are timeless and are not just found in Rudolph’s own buildings: they are not restricted to any one style of construction, location or material.

“Modern architecture’s range of expression is today from A to B. We build isolated buildings with no regard to the space between them, monotonous and endless streets, too many goldfish bowls, too few caves. We tend to build merely diagrams of buildings.”

”One can say that the present tendency to reduce everything to a system of rectangles, both in plan and elevation, is an outgrowth of the modular concept and machine processes. We accept this discipline but we still long innately for the old play of light and shadow, for something curved.” - Paul Rudolph

Rudolph realized that for architecture to be successful, it must solve modern problems and reflect modern times with a respect for a traditional way of seeing and feeling space.

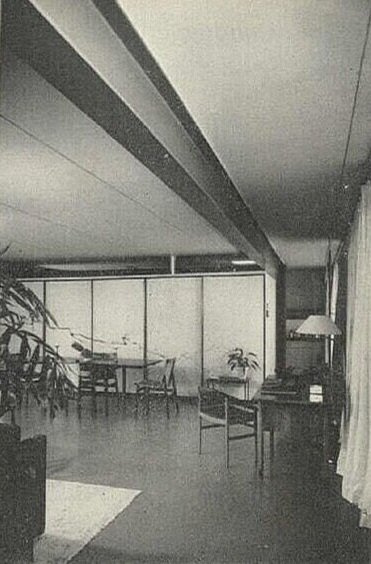

“People, if they think about architecture at all, usually think in terms of the materials. While that’s important, it’s not the thing that determines the psychology of the building. It’s really the compression and release of space, the lighting of that space—dark to light—and the progression of one space to another. Because one remembers in that sense.” - Paul Rudolph

As architecture and design adapt to the changing needs of our modern world - sustainability and climate change; urbanism; affordable housing to name a few - these principles can help us to design and build a better future that keeps and learns from the best of the past.

The New York City-based non-profit 501(c)3 organization was founded by Ernst Wagner, Paul Rudolph’s heir and executor of his estate, to fulfill Rudolph’s wish that an organization be created to preserve and educate others about his architectural legacy. The Institute will promote Rudolph’s design principles through preservation and advocacy efforts, educational programs, public events and maintaining and developing an archive of materials related to modern architecture.

The Institute’s logo is Rudolph’s representation of a human figure in the pen and ink drawings that made his work celebrated around the world. It represents Rudolph’s humanistic view of architecture that emphasizes the power of human beings to create, improve, and reshape their environment with the aid of scientific knowledge, technology and practical experimentation.

Rudolph described architecture as “used space formed to satisfy people’s psychological needs.” This definition places the user at the center of architectural experience and considers human beings as the starting point for any architectural philosophical inquiry.

The Paul Rudolph Institute for Modern Architecture will continue to act as the exclusive worldwide representative for The Estate of Paul Rudolph LLC with regard to licensing third parties for any and all uses of the intellectual property rights of the Works of Paul Rudolph.

If you are interested in becoming involved with the work of the Paul Rudolph Institute, or to find out more about our programs as they develop, please complete the “Contact Us” form and note your interest in this work so we may contact you.

![A chart from the Pew Research Center’s study of Public Trust in Government: 1958-2019 The overall downward trend, from 1964 to the present, is evident. [Note that the largest and steepest drop was in the wake of the mid-1970’s Watergate scandal.] Wh…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a75ee0949fc2bc37b3ffb97/1616438220772-C9X7PWXIHIW0L7MK9ZX1/trust%2Bin%2Bgovt.jpg)