The Nakagin Capsule Tower in Tokyo, designed by Kisho Kurokawa, and completed in 1972—a building of national (and international) importance in the history of Modern architecture.

AN ARCHITECTURE OF OPTIMISM

Looking at it today, Tokyo’s NAKAGIN CAPSULE TOWER—with its streaky surfaces, hanging cables, and patina of aging—the building may seem like it emerged from a dystopian Japanese anime series, the kind which shows a future world of high-tech slums. Several times, its immanent destruction has been announced—and now it seems to be edging closer to that fate—though a final decision may not have yet been made. Indeed, it has real problems that only a well-funded restoration program could fully solve. But such a program (however costly) would be worth it:

Because this building, above all, is about OPTIMISM

Tokyo, at the end of World War II, showing the devastated city. On a plain of destruction, only a few of the more substantially-constructed buildings remained (and even those were terribly damaged.)

A CONTEXT OF DESTRUCTION, REBIRTH—AND QUESTIONING

At the end of World War II, Japan was devastated: It had lost its empire of colonies and territories; it had nearly 3,000,000 dead (military personnel and civilians), its cities and industrial infrastructure were in ruins, and it had to face a history of war-crimes, and adjust to a vastly new form of government. Perhaps most difficult of all was to submit to having a subservient position in the world.

A combination of post-war policies and actions—economic, political, and diplomatic—brought forth the “Japanese Economic Miracle,” and by the mid-1950’s the economy had exceeded pre-war levels, and with that came the beginnings of a consumer economy. But destroyed urban areas had yet to recover, and widespread quality-of-life improvement for all was a long way off.

Kenzo Tange’s metal-covered Shizuoka Press and Broadcasting Tower, of 1966, looked like its cantilevered wings could start rotating at any movement.

METABOLISM

Even with its economic renewal, no country—and especially a highly-integrated, intensely hierarchal, and sophisticated civilization as Japan had been—could go through such trauma and change without being profoundly affected—to the point where the deepest assumptions about life were ripe for questioning and reevaluation. That is the historical context in which a major Japanese architectural movement, METABOLISM, came to exist.

While its birth involved a large number of influences and architects, meetings, conversations, and changes in personnel, what resulted—by the time of the proclamation of its existence in 1960—was a movement of immense creative vitality. Since the Metabolist Manifesto spoke in forward-looking generalities, there were no rigid rules about what building or urban design had to look like.

From the METABOLIST MANIFESTO:

“Metabolism is the name of the group, in which each member proposes further designs of our coming world through his concrete designs and illustrations. We regard human society as a vital process - a continuous development from atom to nebula. The reason why we use such a biological word, metabolism, is that we believe design and technology should be a denotation of human society. We are not going to accept metabolism as a natural process, but try to encourage active metabolic development of our society through our proposals”

Like the the BAUHAUS, the architectural works of the Metabolist architects were diverse in form. But—equally like the BAUHAUS—there’s a shared family resemblance among their designs. Their buildings embraced a characteristic frequently found in future-oriented projects: a machine-like vocabulary—even sometimes looking like giant machines. Also, their buildings had a module or “systems” look—as though constructed from a kit-of-parts, with the implication that such a modular approach would allow for ongoing change and growth. Finally, perceiving the titanic challenges involved in rebuilding the country, rising population growth, and the issues of land use, urban design, infrastructure, and re-industrialization, they “thought big”—and so came up with designs of “mega-structural” scale.

Kyoto International Conference Center by Sachio Otani

Aquapolis City, for the Okinawa Ocean Expo, by Kiyonori Kikutake

The Yamanashi Broadcasting and Press Centre, by Kenzo Tange

Beyond these formal qualities, what one discerners in Metabolist designs are HOPE, a sense of NEW OPPORTUNITES, OPTIMISM, and looking to A BETTER FUTURE—often through architectural expressions of the possibilities of technology. These are not trivial or side-effects of their designs: looking at the multitude of sketches, writings, proposals, drawings, and models they produced—and they were prolific!—one senses the JOY of CREATION.

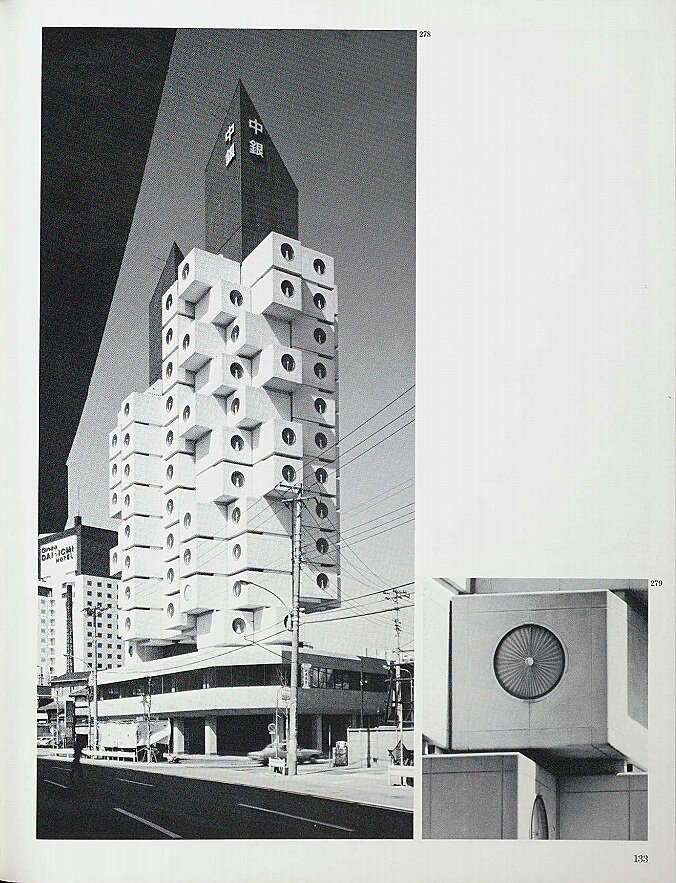

Arthur Drexler’s book, “Transformations in Modern Architecture” had a page that was devoted to the NAKAGIN CAPSULE TOWER. Shown when it was fresh and new—an a vision for the future of architecture.

NAKAGIN CAPSULE TOWER: INNOVATIVE IN CONCEPTION AND CONSTRUCTION

The NAKAGIN CAPSULE TOWER was designed by one of the leading Metabolist architects: Kisho Kurokawa (1934-2007). It was constructed between 1970 and 1972—and is considered one of the the prime examples of Metabolism (and one of the few of their many proposed designs to get built)

It is mixed-use, providing space for both residential and office use, and is composed of two concrete towers, to which are attached 140 self-contained prefabricated capsules. Each capsule is approximately 8 feet by 13 feet, with a circular window at one end, and each is connected to the main shafts only four high-strength steel bolts

As with such capsule-oriented designs, construction combined both on-site work (the reinforced concrete core towers and the main lines of the electrical and mechanical systems, as well as stairs and elevators) —and— off-site work (the prefabricated capsules, whose parts were fabricated and assembled in a factory.) The capsules are lightweight steel-truss boxes, clad in galvanized, rib-reinforced steel (which was coated with rust-preventative paint and finished with a sprayed-of glossy spray coat).

In our time, when factory-fabricated residential structures and hotels are an increasingly encountered fact, none of the above may seem exciting enough to gain our attention today—yet when NAKAGIN CAPSULE TOWER was created, the approach and technologies were new and hardly tried. Moreover, the form of the tower—which so directly expressed its modular construction—was fresh and powerful.

It was thought that the market for the apartment units would be Tokyo’s abundant population of white-collar bachelors, and each residential capsule included carefully designed, built-in kitchen appliances and cabinets (including a built-in bed, television set, and tape recorder, and a fold-out desk.) An ultra-compact bathroom unit, not much larger than the size of an airplane lavatory, uses part of the capsule space. A large, circular window—each of which originally had an inventive radial shade— is seen on-axis from the entry door.

The inside of the tower’s residential capsules were all fitted out with built-in cabinetry and equipment.

Inside a residential capsule, looking toward the circular window, showing built-in cabinetwork and bed.

An axonometric diagram, from a Japanese publication, showing the layout of a single capsule. The view is looking downward on the unit, and included in this drawing are: the single circular window (at the lower-right); the bed (the large, light rectangle under the window); the full bathroom (at upper-left): and the wall of built-in cabinets, including a fold-out desk, integral tape recorder and TV, and storage (all along the upper-right wall). Some indication of the unit’s connections to building services (power, telephone, plumbing) seems to be indicated by the pipes and conduits emerging at the top-center of the drawing. A marvel of compact, efficient (and delightful) planning, the Nakagin Capsule Tower is a monument of Modernism that is worth saving.

Included in the Museum of Modern Art’s comprehensive exhibit, Transformations in Modern Architecture and catalog, (shown above) were several other examples of the modular/capsule approach to building design.

PREDEDENTS, CONNECTIONS, AND CROSS-CURRENTS

METABOLISM—of which this building is a prime example—had connections to the thinking and works of architects (as well as movements and cultural trends) in other parts of the world. This could be seen in the major 1979 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, “TRANSFORMATIONS IN MODERN ARCHITECTURE” and its catalog-book (in both of which Paul Rudolph was also prominently included.) Not only did it prominently show the NAKAGIN CAPSULE TOWER, but it also included buildings—by other architects in France and Japan—with similar ideas and configurations.

Paul Rudolph, more than a decade before the NAKAGIN CAPSULE TOWER, had been thinking along these lines lines—as is shown in his 1959 project for a Trailer Apartment Tower. About this design, Rudolph said:

Rudolph’s 1959 design for a tower of prefabricated residential units, which would be mounted to a central shaft—not unlike the concept for NAKAGIN CAPSULE TOWER, which was built over a decade later in Japan.

“For a number of years now I have felt that one way around the housing impasse would be to utilize either mobile houses or truck vans placed in such a way that the roof of one unit provides the terrace for the one above. Of course the essence of this is to utilize existing three dimensional prefabricated units of light construction originally intended as moving units but adapted to fixed situations and transformed into architecturally acceptable living units. One approach would be to utilize vertical hollow tubes, probably rectangular in section, 40 or 50 stories in height to accommodate stairs, elevators and mechanical services and to form a support for cantilever trusses at the top. These cantilever trusses would give a ‘sky hook’ from which the three dimensional unit could be hoisted into place and plugged into its vertical mechanical core.”

In the following decades, Rudolph would continue to explore variations of this idea—part of his ongoing interest in modularity—at various scales and in a variety of projects (and you can read about those projects here. )

There are further verifiable connections and possible cross-influences: Rudolph had been aware of the basic tenets of the METABOLIST movement from its official founding. Along with fellow architects Alison and Peter Smithson and Louis Kahn (and other distinguished practitioners from around-the-world), he was present at the 1960 World Design Conference in Tokyo, where the ideas of the Metabolists were first announced. Rudolph even proposed to Arthur Drexler, then curator of the Museum of Modern Art’s Architecture and Design Department, that Kikutake’s Metabolist Marine City be included in the museum’s 1960 exhibition Visionary Architecture—the exhibition which introduced the ideas of the Metabolists to the United States.

Megastructures were a key part of METABOLIST thinking—and one could argue that the Nakagin tower is a “megastructure in miniature.” Like Paul Rudolph’s Graphic Arts Center (one of Rudolph’s megastructure designs), Kikutake’s Marine City is constructed of tower cores and plug-in residences set atop artificial landmasses—and the parallels shared by the works of the two architects are striking (and you can read more about these resonances here.)

LIFE Magazine’s December 15, 1972 Special Double Issue on the Joys of Christmas included an article showing Paul Rudolph exploring the potential of LEGO bricks to create architectural forms and configurations. Among the designs shown, for which he used the LEGO system, is a tower made of prefabricated residential units that would be mounted to vertical structural supports and service shafts—another clear manifestation of the idea that he first began to work with near the end of the 1950’s

Architectural historian Reyner Banham’s book, “Megastructure: Urban Futures Of The Recent Past” was his “first approximation” look at the history of this important international architectural movement—one to which METABOLISM contributed key thinking and iconic projects. The original edition was published in 1976, and is long out-of-print—but Monacelli Press has come out with a new edition (and, as before, Rudolph’s LOMEX project is featured on the cover.)

The streaked façade of the capsule tower.

DECADES OF USE AND SUCCESS—THEN DECLINE

Kelvin Dickinson has observed that “50 years is a dangerous age” for a building: it’s just about at that point in a building’s life when—

mechanical and electrical systems have worn-out, and need replacement and/or updating

significant repairs are probably needed to the building envelope

changing demographics or business practices may have made the original use of the building seem old-fashioned and less attractive to tenants—and so the building may need to be adapted for re-use

changing regulations can require upgrades or alterations (i.e.: for energy use; accessibility; containing toxic materials; fire safety; and earthquake or storm resistance)

And so a tough decision has to be made on whether to make the major investments needed to maintain and revivify a building -or- to demolish it and rebuild.

The NAKAGIN CAPSULE TOWER not only became world-famous as a work of architecture—but also had full occupancy (with a waiting-list). So it was a success, but—

But the building is approaching 50 years-of-age, and has accumulated numerous problems—ones that can’t be dismissed, and which will take large expenditures to fix. Also: it sits on land which can be more profitably utilized if a higher building is built on that site—and that always energizes the forces arguing for demolition.

Japan Forward’s recent article on the projected destiny of the NAKAGIN CAPSULE TOWER

CAN THE NAKAGIN CAPSULE TOWER BE SAVED?

The seemingly imminent destruction NAKAGIN CAPSULE TOWER is being protested by some residents, by the Japanese Institute of Architects, and by admirers world-wide—and there’s even a Facebook page for the SAVE NAKAGIN CAPSULE TOWER PROJECT

WANTED: VISION

It takes vision—being able to understand design greatness—to see the value of a work of architecture beyond immediate economic pressures.

The Facebook page for the SAVE NAKAGIN CAPSULE TOWER PROJECT

Of course, practical issues must be dealt with—but the motivation (to come up with creative solutions to those challenges) only emerges when there’s a clear sense that a building is worthy of the significant effort and investment needed to save it.

We’ve seen what happens when that energy does not come forth—because that’s recently happened with two of Paul Rudolph’s works: the Burroughs-Wellcome headquarters and research center in Durham North Carolina, and the Orange County Government Center in Goshen, NY: they were both demolished. These were two of the most significant buildings of Paul Rudolph’s career—high points showing how he could powerfully, beautifully, and practically integrate creative forms and space-making with corporate, scientific, and civil functions—and now they’re lost forever.

Great architecture is part of a country’s cultural heritage. The NAKAGIN CAPSULE TOWER is one of Japan’s national treasures (as were those Rudolph buildings for the US)—and they were as significant as each country’s most valued artworks, documents, and historic monuments.

Beyond their national significance, these are international treasures that transcend borders: they are part of the profound legacy given by great artists, architects, and thinkers and creators of all kinds.

We must not lose these gifts to us. Save the Nakagin Capsule Tower. Save Culture.

UPDATE — END OF AN ICON OF MODERN DESIGN?

Searching for “Nakagin Capsule Tower” on Amazon yields several items which testify—as this screen-capture shows—to the esteem with in the building is held: several books, a video, and even a face-mask.

The NAKAGIN CAPSULE TOWER is incontrovertibly a Modern architecture landmark—one of international fame and importance. Its design has inspired several books, a video, clothing (including a face-mask)—and even atmospheric music: “Sleepless in Nakagin Capsule Tower” from the album "E S P E R”—you can hear an excerpt from the song here. [Yet another example of the fascinating relationship between architecture and music, which we explored in another article.]

The moves to remove the tower began a number of years ago. There was push-back from the tenants and from the Japanese architect’s professional association; various counter-proposals were put forth; funding to save the building was sought; the 2008 recession put a break on things—and, most recently, the Covid shut-down also created a delay in moving ahead to demolition. But all that, it seems, has not been enough to save the building. According to a July 16, 2021 article by India Block, on the Dezeen website:

. . . .owners and residents of Nakagin Capsule Tower have decided to sell their homes and divvy up the capsules after attempts to find a buyer prepared to fund the restoration failed.

A module is already on display at Japan's Museum of Modern Art Saitama and the Centre Pompidou in Paris is reportedly keen to acquire one for its collection.

The owners are now crowdfunding to renovate the remaining 139 capsules so that they can be donated to institutions, or be relocated elsewhere in Tokyo and rented out to people who want to experience staying in one.

In 2007 the collective of owners announced they would sell to a developer who planned to demolish the building and build a new apartment block in its place.

However, the developer went bust in the 2008 recession, leaving the future of the tower uncertain.

In 2018 the owners started renting out the capsules on a monthly basis to architecture enthusiasts while the search for a buyer continued, until the coronavirus pandemic shut down negotiations.

A few days later, a July 19, 2021 article by Ryan Waddoups on the SURFACE website, reports:

The tower’s fate now appears to be sealed. Despite attempts to find a buyer who would fund its restoration, building owners have decided to disassemble the tower to make way for new development. “Aging has been a major issue in recent years,” Tatsuyuki Maeda, who owns 15 capsules, told a local magazine. “I was looking for a developer who would leave the building standing while repairing it. We think that it’s difficult for the management association to take measures against aging.”

The owners are currently crowdfunding to renovate the capsules so they can be donated to museums or relocated throughout Tokyo for short-term stays. One module is already on display at Japan’s Museum of Modern Art Saitama; the Centre Pompidou has also expressed interest in acquiring one for its permanent collection. Nicolai Ouroussoff, former architecture critic for the New York Times, wrote during one of the many demolition scares that the Nakagin Capsule Tower is “the crystallization of a far-reaching cultural ideal. Its existence also stands as a powerful reminder of paths not taken, of the possibility of worlds shaped by different sets of values.” And while losing one of the few examples of this rare architectural movement feels like an undoubtedly sad occurrence, it’s rare to see buildings physically preserved as art post-demolition.

Although one hopes for a last-minute reprieve from a far-sighted and wealthy architecture-loving patron—such things have happened in the history of preservation—at the moment the future of the NAKAGIN CAPSULE TOWER looks bleak. We’ve lost numerous masterworks of Modern Architecture—the recent demolition of Paul Rudolph’s BURROUGHS WELLCOME headquarters and research center being a particularly great and painful loss. Such short-sighted destruction of our national and international cultural treasures must stop.

The Nakagin Capsule Tower in Tokyo—an icon of Modern Architecture

IMAGE CREDITS

NOTES:

The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation gratefully thanks all the individuals and organizations whose images are used in this non-profit scholarly and educational project.

The credits are shown when known to us, and are to the best of our knowledge, but the origin and connected rights of many images (especially vintage photos and other vintage materials) are often difficult determine. In all cases the materials are used in-good faith, and in fair use, in our non-profit, scholarly, and educational efforts. If any use, credits, or rights need to be amended or changed, please let us know.

When/If Wikimedia Commons links are provided, they are linked to the information page for that particular image. Information about the rights for the use of each of those images, as well as technical information on the images, can be found on those individual pages.

CREDITS, FROM TOP-TO-BOTTOM and LEFT-TO-RIGHT:

Capsule Tower, general view: photo by Kakidai, via Wikimedia Commons; Capsule Tower, looking up to capsules; photo by scarletgreen, via Wikimedia Commons; Tokyo, at the end of World War II: photo by 米軍撮影 , via Wikimedia Commons; Shizuoka Press and Broadcasting Center in Tokyo: photo by Jonathan Savoie, via Wikimedia Commons; Kyoto International Conference Center: photo by Daderot, via Wikimedia Commons; Model of Aquapolis; photo via Wikimedia Commons; Page devoted to the Nakagin Capsule Tower, from the “Transformations In Modern Architecture” book, via the Museum of Modern Art on-line archive website; View of the Nakagin Capsule Tower: photo by marcinek, via Wikimedia Commons; View of the Nakagin Capsule Tower: photo by yusunkwon, via Wikimedia Commons; View of interior of a residential capsule, showing built-in cabinetwork and equipment: photo by Dick Johnson, via Wikimedia Commons; View of interior of a residential capsule, looking toward window and bed: photo by Chris 73, via Wikimedia Commons; Page devoted to projects similar to the idea of the Nakagin Capsule Tower, from the “Transformations In Modern Architecture” book, via the Museum of Modern Art on-line archive website; Paul Rudolph’s drawing of his 1959 design for a Trailer Apartment Tower, © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation; Cover of “Megastructure” book: screen capture from the Amazon web page for the book; View of the exterior of many capsules: photo by Michael, via Wikimedia Commons; Japan Forward’s article about the Nakagin Capsule Tower: screen capture of their page with the article; Save Nakagin Capsule Tower Project’s Facebook page: screen capture from Facebook; Nakakin Capsule Tower merchandise available from Amazon (books, video, facemask): screen-capture from Amazon web search; General exterior view of Nakagin Capsule Tower: photo by Jordy Meow, via Wikimedia Commons