I. M. Pei’s Dallas City Hall, completed in 1978. Of this project, he said: “When you do a city hall, it has to convey an image of the people, and this had to represent the people of Dallas. . . .The people I met—rich and poor, powerful and not so powerful—were all very proud of their city. They felt that Dallas was the greatest city there was, and I could not disappoint them.”

CELEBRATING I. M. PEI

I.M. Pei (1917 – 2019) as photographed in 2006.

IEOH MING PEI (April 26, 1917 – 16 May 16, 2019) lived a long and celebrated life. Well before his passing at age 102, he had received about every award and prize offered within in the profession of architecture.

While some of his projects had problems in their initial acceptance, usually they went on to be prized and a source of local pride—the Louvre Pyramid (part of the Grand Louvre project) being the prime example (and the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum being another.) Other projects were well appreciated from the start, like the Mesa Laboratory of the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Colorado, the East Building of the National Gallery in Washington, the Myerson Symphony Center in Dallas, the Dallas City Hall, and the OCBC Centre skyscraper in Singapore.

These are buildings whose ideas remain FRESH - one of the highest values to which a Modern architect could aspire - and one rarely achieved.

THE SPECIAL COMBINATION WHICH IS PEI’S ARCHITECTURE

Initially, it is not easy to identify what distinguishes Pei’s oeuvre from the other prominent architects working in his era—-the second-half of the 20th Century: firms which also received commissions of prominence, high cultural status, and significant budgets. One of the the terms that keeps coming up, when looking at Pei’s work, is “tailored”: his buildings are as carefully planned and crafted as a custom suit—and they have that quality of “Opulent Restraint”. Pei and his team focused upon every detail—not only the parts themselves, but also making them harmonious with the building-as-a-whole. Materials were chosen that both convey an investment in the present and also an eye to the future (they are substantial and wear well.) Craftsmanship is prized—and execution is carefully monitored. His buildings are much in-character with the I. M. Pei that most people encountered: a refined and charming gentleman—who was articulate and highly persuasive when “making the case” for his design decisions. But also he seemed to be someone that was personally reserved: a man whom you observe and listen-to with attention, and to whom you would not push too many questions—out of profound respect.

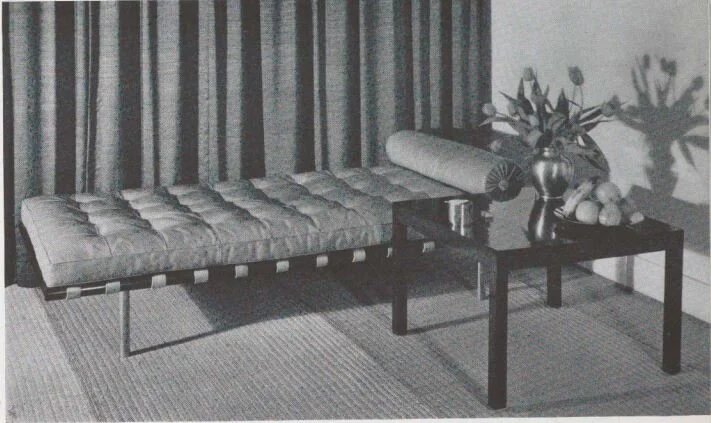

SOM’s Republic Newspaper Plant & Offices. As with Pei’s work, it exemplifies elegance in conception and execution..

Yet other architects, contemporary with Pei, could (and did) produce designs as refined and as “tailored.” The best of Skidmore Owings, and Merrill’s corporate office buildings—like their Lever House, or their Pepsi Cola Building on Manhattan’s Park Avenue, or One Liberty Plaza in downtown Manhattan, or their Republic Newspaper Plant & Offices in Columbus, Indiana—could rival Pei’s work in the thoughtful way that each structure solved problems, and the elegance of the detailing and execution. Other architects also worked in this direction—Craig Elwood, and the early work of Paul Rudolph, are examples. Since Pei has rivals in the domain of well-crafted Modernism, what raises his profile must be something in addition to those architectural values.

The other vital ingredient of what made a Pei building a “Pei” might be called The Grand Gesture. We are familiar with “grand gestures” in life: it might be a philanthropist donating a stunning sum to erect a needed facility (like a hospital or playground), or an employer granting an surprise bonus and holiday to her team—or even Oprah giving a car to every member of her studio audience. These “Grand Gestures” all share several characteristics:

they are Big (and vividly noticeable) in the expenditure of resources, effort, or time

they are Unexpected

they have emotional Impact

they Delight

and they are Beautiful in the way they lift the spirit

It is architectural Grand Gestures which Pei, in combination with the caring “tailored” quality of his work, used to make his work rise above just being “elegant”—and we see such gestures in every one of his most memorable buildings:

the inverted geometry of the Dallas City Hall

the timeless platonic power of the Louvre Pyramid

the relentless and striking angles of the National Gallery

the unexpected-form of his Macau Science Center

the collage of masses, emerging from the water, of his Rock & Roll Hall of Fame

the vertiginous space of the JFK Library

the curved glass “lens” floating upward from a rectilinear form, at the Myerson Symphony Center

the knife-edges of his Gateway towers in Singapore (even more famously used at the National Gallery)

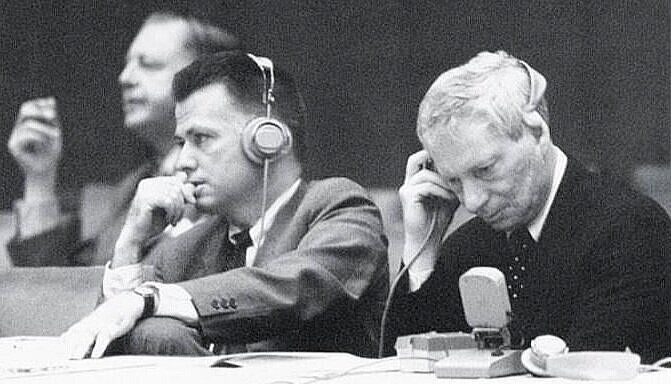

It is worth noting that Pei himself never identified this recipe as his modus operandi. In presenting his work—to clients, stakeholders, and the public—Pei consistently maintained that his forms and spaces were the logical outcome of a careful analysis of the programmatic challenges of each commission. His presentations were masterpieces of persuasiveness-through-clarity: when presenting, he took the clients step-by-step through the development of the designs, so that they saw (or believed they saw) the inevitableness of Pei’s architectural decision. While this too is a kind of showmanship, the clients evidently appreciated the pragmatic mode in which Pei communicated—and strongly supported him through some challenging building projects.

“The essence of architecture is form and space, and light is the essential element to the key to architectural design, probably more important than anything. Technology and materials are secondary.” — I. M. Pei

The most famous of I. M. Pei’s buildings—the ones referenced above—are well-known to most people. So we’d like to celebrate his birthday with some Pei designs that you might not be familiar with, or show some fresh views of well-known ones…

The William L. Slayton House is one of the very few residences that Pei designed, and an early project (being completed in 1960). Its signature system of roof vaults is evocative of one of Le Corbusier’s buildings: the Maisons Jaoul (a design from about a half-decade before the Slayton House)—with which Pei probably was familiar. The Slayton House is on the National Register of Historic Places, and you can see the full report on it (which includes drawings and photos) here.

The Louvre Pyramid—the main entry to the Louvre Museum—must be one of the most known images in Paris. What makes this photograph of it—sitting within the courtyard of the hundreds-of-years-old Louvre Palace—so striking is that it feels like a vintage engraving.

A comparison of the size and silhouettes of pyramids around-the-world—from ancient-to-modern. The smallest, on this chart, is the Louvre pyramid (the small, blue triangle at the bottom-center.) A larger, easier-to-read version of this chart can be seen here.

The Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, in Cleveland, was dedicated in 1995. Even though it is one of Pei’s most well-known late projects its striking collage of nearly clashing masses never ceases to startle - as can be seen in this photograph by Lance Anderson.

The Gateway is a commercial development in Singapore which was completed in 1990.. It consists of two towers that are trapezoidal in plan. Both of the towers are 37 storeys tall, and the wedge-shapes of their corners creates a striking effect..

The Macau Science Center is a science museum and planetarium not far from Hong Kong. The project—with its unusual forms, set by the water—began in 2001 and was opened in 2009.

A night-time view of the Macau Science Center.

Pei’s Bank of China Tower is famous for the the large diagonal geometry of its facades, almost always seen in distant views. But most people are not familiar with it close-up, and we thought it would be worth showing that aspect of the building—the one that impacts Hong Kong residents and the building’s users. Above is view of one of the building’s sides, near the bottom—showing the refinement of patterning and attention to material and detail which Pei brought to every project.

I. M. Pei’s Bank of China Tower (center-left) in Hong Kong, identifiable by its’ diagonal/triangular geometries, was completed in 1990. We thought it would be good to show it in proximity to one of the pair of towers of Paul Rudolph’s Bond [Lippo] Centre (center-right), which were completed a few years earlier in 1988.

IMAGE CREDITS

NOTES:

The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation gratefully thanks all the individuals and organizations whose images are used in this non-profit scholarly and educational project.

The credits are shown when known to us, and are to the best of our knowledge, but the origin and connected rights of many images (especially vintage photos and other vintage materials) are often difficult determine. In all cases the materials are used in-good faith, and in fair use, in our non-profit scholarly and educational efforts. If any use, credits, or rights need to be amended or changed, please let us know.

When/If Wikimedia Commons links are provided, they are linked to the information page for that particular image. Information about the rights for the use of each of those images, as well as technical information on the images, can be found on those individual pages.

CREDITS, FROM TOP-TO-BOTTOM:

Dallas City Hall: photo by Loadmaster (David R. Tribble), via Wikimedia Commons; Photo portrait of I. M. Pei: U.S. State Department photograph, via Wikimedia Commons; Republic Newspaper Plant & Offices, by SOM: photo by Don47203, via Wikimedia Commons; William L. Slayton House: photo by Smallbones, via Wikimedia Commons; Louvre Pyramid: photo by Christopher Michel, via Wikimedia Commons; Comparison of size of pyramids chart: by Cmglee, via Wikimedia Commons; Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum, photo by Lance Anderson, via Wikimedia Commons; The Gateway, Singapore: photo by Someformofhuman, via Wikimedia Commons; Macau Science Center: photo by AG0ST1NH0, via Wikimedia Commons; Macau Science Center-night view: photo by Diego Delso, delso.photo, License CC-BY-SA, via Wikimedia Commons; Base of Bank of China tower: photo by Emasmeso, via Wikimedia Commons; Bank of China tower and Bond Center tower: photo by Bernard Spragg. NZ, via Wikimedia Commons

![I. M. Pei’s Bank of China Tower (center-left) in Hong Kong, identifiable by its’ diagonal/triangular geometries, was completed in 1990. We thought it would be good to show it in proximity to one of the pair of towers of Paul Rudolph’s Bond [Lippo] C…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a75ee0949fc2bc37b3ffb97/1619472490202-HK5KFALLDMP84GSTEAMY/Bank+of+china+and+Rudolph+tower.jpg)