A compelling photo by G. E. Kidder Smith of Paul Rudolph’s Burroughs Wellcome US headquarters and research center, shown near the time of the building’s completion. Here, the photographer gives us an image which simultaneously captures the architecture’s play of volumes, structural and geometric adventurousness, aspects of its siting, and scale. Photo courtesy of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

PHOTOGRAPHIC POWER

What’s more important: a great building -or- a great photograph of it?

It’s an impossible question to answer—not because of its difficulty, but rather: because the question itself attempts to compare such different entities. The “actuality” of architecture—the way one would come to know a building, in-person, by entering and moving through it and experiencing the spaces sequentially (truly a four-dimensional phenomenon), and also through other senses (sound and touch)—is wholly different from the way that one takes-in the information embodied in a two-dimensional photograph.

Then how are architectural photographs important?

The answer: in their potential for influence.

ENDURING AND WIDESPREAD INFLUENCE

No matter how many people see a building in-person, an uncalculable greater number can see it in photographs—-and those viewings continue onward, even if the building ceases to exist.

Probably the most famous case is Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion. It was built for a 1929 international exposition, and—from the time of its inauguration-to- its demolition—it only existed for less than a year. Since then, it has been known from a handful of photographs and its plan.

Mies’ Barcelona Pavilion, was built in 1929 and demolished within the following year. Of the handful of photographs recording what it looked like when extant, this is probably the most famous image.

Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion of 1929 was built for an international exposition. It is preponderantly known only through a handful of photographs and two drawings (the plan, above, and a detail of a typical column.) Yet on the strength of this small group of images, it gained—and retains!—world-class status as one of the ultimate icons of architectural Modernism.

Of that small group of photographs, the most famous image is probably the one shown above. Those photos, combined with the plan drawing, have been included in countless books, articles, lectures, curricula—-and, even more important: they’ve become integrated into the thinking of every Modern architect. [We’ve written here about Rudolph’s own interest in the Barcelona Pavilion, and also here about his relationship to Mies’ work.] Now, coming-up on a century since it’s demolition, this iconic building continues to resonate through architectural education, scholarship, and practice— mainly because of photographs.

Further: try as we may to visit the great, iconic examples of architecture, they are just too dispersed. So even a devoted architectural traveler could spend decades just trying to see most of them. So, practically speaking, we have to experience and learn about most of of the world’s architecture from photographs.

THE GREAT PHOTOGRAPHERS OF MODERN ARCHIECTURE—CREATING THE ICONS WE REMEMBER

The 20th and early 21st centuries have been graced with architectural photographers that can be considered “artists-in-their-own-right”. That’s because they’ve not only been able to capture the formal essence of architectural works, but—like visual alchemists—they have also created images which (through their choices of point-of-view, lighting, focus, and composition) have virtually created the vital identities of those buildings.

Prime examples would be the powerful photo that Ezra Stoller took of Paul Rudolph’s Yale Art & Architecture Building—it’s the image we “have in our head” when we think of the building; Yukio Futagawa’s chroma-rich capturing of the interior of Rudolph’s Tuskegee Chapel; and Balthazar Korab’s photos of the soaring wings of Saarinen’s TWA “Flight Center” terminal at Kennedy Airport. To many of us, those images are the building.

Ezra Stoller’s photograph of the exterior of Paul Rudolph’s Yale Art & Architecture Building became the iconic image of it—and it’s included on the cover of his book on that famous building.

Each issue of Futagawa’s journal, GA (Global Architecture) focused on one or two buildings. This one is on Rudolph’s Tuskegee Chapel and Boston Govt. Service Center—and Tuskegee is on the cover.

Balthazar Korab photographed a number of designs by Eero Saarinen, including the TWA terminal for Kennedy airport. His photographic work on that project ranged from recording the Saarinen office’s working models, to construction photos (like the one above), to the finished building. Even in its construction stage, when it was only raw concrete, Korab was able to capture the drama of the building. Photo courtesy of the Balthazar Korab Photographic Archive, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

RUDOLPH AND HIS PHOTOGRAPHERS

Paul Rudolph worked with some of the century’s greatest architectural photographers—the ones who are celebrated for working with the leading figures in the world of architectural Modernism. While Rudolph might have been directly involved with some photographers—commissioning them, or requesting that they focus on certain aspects of a building—in other cases, even without Rudolph’s involvement, great photographers have been engaged (by others) to shoot his work; or have done so just out of their own interest in his oeuvre.

While not exhaustive, we’ll review a round-up of many of the photographers who have been focused on the work of Paul Rudolph—and we’ll do this in two parts:

PART ONE (this article) looks at the great architectural photographers of the early-to-late 20th Century, who have worked on Rudolph’s oeuvre.

PART TWO will look at photographers—most still very active—who have more recently focused on Rudolph’s work.

EZRA STOLLER

(1915-2004) When one thinks of architectural photography in America, the name—or rather: the images—of Ezra Stoller are what probably first come to mind. For decades, he photographed many of the 20th Century’s most significant new buildings in the US (by the country’s premier architects), thereby creating an archive of the achievements of Modern American Architecture. More than that, Stoller’s views are some of the most iconic images of that era.

STOLLER AND PAUL RUDOLPH: Of the several photographers that Rudolph worked with, Ezra Stoller is probably the one with which he had the most involvement and lasting relationship. Stoller photographed much of his residential work in Florida—including some of Rudolph’s greatest and most innovative houses like the Milam Residence (as seen on the over of Domin and King’s book on the Florida phase of Rudolph’s career—see image at right), the Walker Guest House, the Umbrella House, and the Healy “Cocoon” House—the Yale Art & Architecture Building in New Haven, Sarasota Senior High School, the Temple Street Parking Garage in New Haven, Endo Labs, the UMass Dartmouth campus, Tuskegee Chapel in Alabama, the Hirsch (later: “Halston”) townhouse in New York City , the Wallace House, Riverview High School in Florida, the Sanderling Beach Club in Florida, and numerous others—including the Burroughs Wellcome US headquarters and research center in North Carolina’s Research Triangle Park. One can access the extensive and fascinating archive of Ezra Stoller’s work (including the Rudolph projects that he photographed) here—and an extensive selection from throughout Stoller’s career (including numerous images of Rudolph’s work) can be viewed in the book “Ezra Stoller, Photographer” (see cover at right).

The first monograph on Rudolph which featured extensive color photography, all of which was done by Futagawa.

YUKIO FUTAGAWA

(1932-2015) The dean of architectural photography in Japan, and with a world-wide reputation, for over six decades Futagawa made magnificent and memorable photos of important buildings (new and traditional) around the world. Interestingly, he created his own “platform” to publish his work: he founded GA (“Global Architecture”), GH (“Global Houses”), and published other series and individual books. Those contained not only of photography, but also architectural drawings and full project documentation of distinguished works of architecture.

FUTAGAWA AND PAUL RUDOLPH: Futagawa traveled the US to make the photographs for the monograph, “Paul Rudolph” (part of the Library of Contemporary Architects series published by Simon and Schuster)—and the archives of the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation posseses a note by Rudolph, testifying to his appreciation of Futagawa’s work. In the GA series, he published one on the Tuskegee Chapel and the Boston Government Service Center. Futagawa extensively photographed the work of Frank Lloyd Wright and, as part of the GA series, he asked Rudolph to contribute the introductory essay to the issue on Wright’s Fallingwater. He also published the large monograph on Rudolph’s graphic works (copiously including his famous perspective drawings): Paul Rudolph: Architectural Drawings.

Kidder Smith’s two-volume “A Pictorial History of Architecture in America,” published in 1976, includes Rudolph’s work. Below: one of his photographs of the Niagara Falls Central Library, taken near the time of its completion. Photo courtesy of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

G. E. KIDDER SMITH

(1913-1997) Along with the other ultra-prominent names we’ve been mentioning, in the world of architectural photography, we must include G. E. (George Everard) Kidder Smith. Trained as an architect, Kidder Smith was not only a photographer of architecture, but also an historian-writer, exhibit designer, and preservationist (helping to save/preserve the Robie House and the Villa Savoye.) His numerous books are still important resources for anyone doing research on the architecture of America and Europe His series of “Build” books (“Brazil Builds” “Italy Builds” “Switzerland Builds” “Sweden Builds”) provide abundant images and information about the rise of Modern architecture in each of those countries.

KIDDER SMITH AND PAUL RUDOLPH: Kidder Smith’s “A Pictorial History of Architecture in America” is a 2-volume work that was published in 1976, and—utilizing the photographs that Kidder Smith had made—it covers all eras of American architectural history, region-by-region. Kidder Smith must have admired Paul Rudolph’s work, for it shows up throughout this major, encyclopedic work, and includes: Rudolph’s Boston Government Service Center, Tuskegee Chapel, Niagara Falls Central Library, UMass Dartmouth, the Orange County Government Center—and Burroughs Wellcome (whose double-page spread image is the photographic climax at the end of Volume One.). This set of buildings are of particular poignance and and meaning to us, as they include a major Rudolph building that has been altered/disfigured (Orange County); and three which are currently threatened (Boston, Niagara Falls, and Burroughs Wellcome.)—and we are using Kidder Smith’s images to help fight for their preservation.

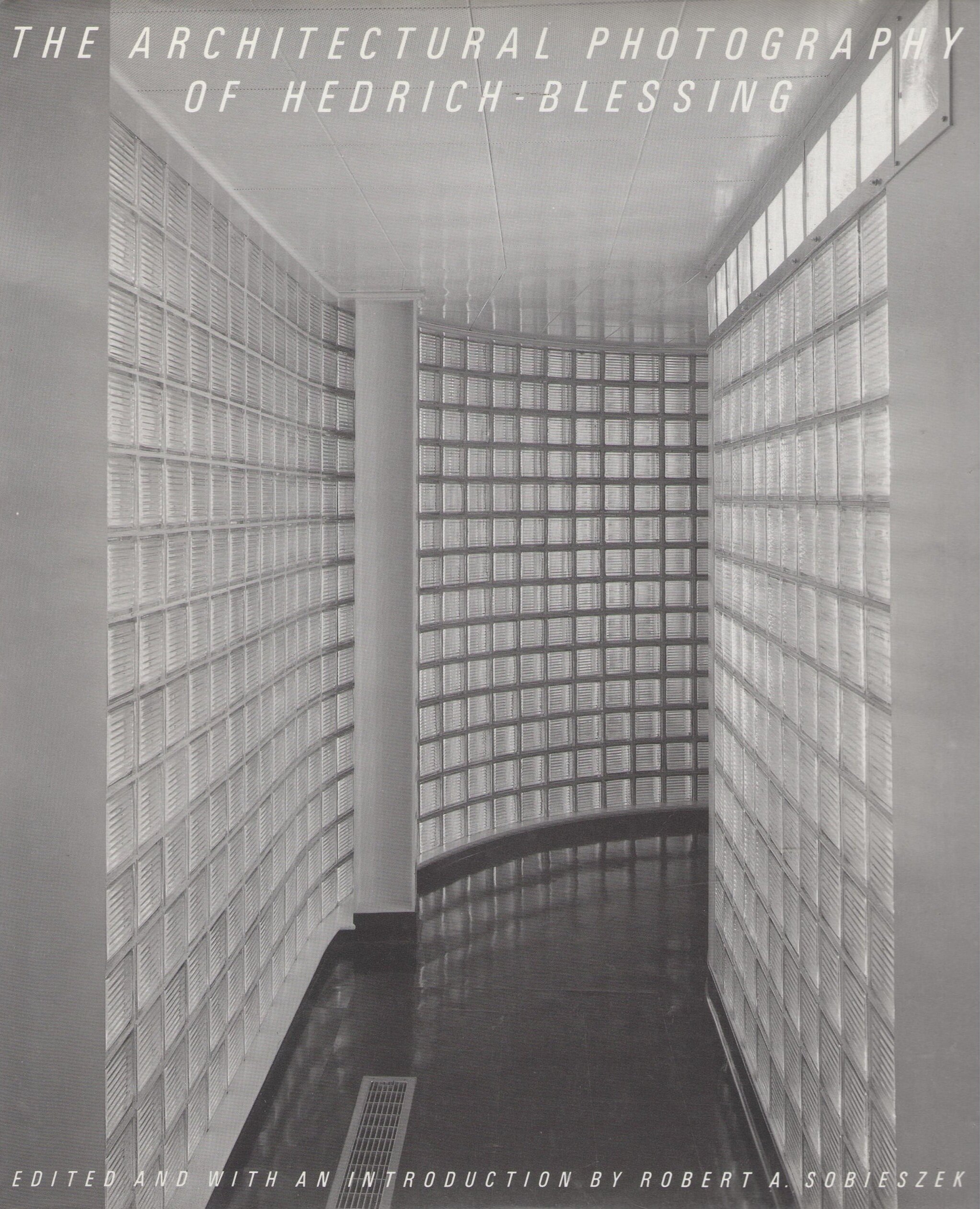

This monograph from 1984 shows work from the several generations of photographers who have worked for Hedrich-Blessing, and the book includes an image of Paul Rudolph’s Christian Science Student Center. An even larger monograph of Hedrich-Blessing’s work was published in 2000, which also included that photo of Rudolph’s building.

HEDRICH-BLESSING

(1929-Present) The other photographers of Rudolph’s work, mentioned in this article, were primarily based on or towards the US’ East Coast. But for the middle of the country, the kings of architectural photography were Hedrich-Blessing. The firm was founded in 1929 by Ken Hedrich and Henry Blessing and—though based in Chicago and famous for photographs of buildings in that region—they have done work all over. Among the distinguished architects, whose work they photographed, were: Wright, Mies, Raymond Hood, Keck and Keck, Albert Kahn, Adler & Sullivan, SOM, Harry Weese, Breuer, Saarinen, Gunnar Birkets, Yamasaki, and Alden Dow. Since its founding, the firm has employed several generations of photographers, and is still very much active today.

HEDRICH-BLESSING AND PAUL RUDOLPH: To our present knowledge, Hedrich-Blessing did not photograph many of Paul Rudolph’s buildings. [Perhaps because Rudolph did not build much in their part of the country. That may have been different had Rudolph become dean of IIT’s School of Architecture in Chicago—an offer he briefly considered.] We do know of at least one superb photo Hedrich-Blessing took of his Christian Science Student Center. This building, which Rudolph designed in 1962 near the University of Illinois Champaign-Urbana, was unfortunately demolished in the mid-1980’s. So it is important that we have Hedrich-Blessing’s photograph, which was taken by their staff photographer Bill Engdahl in 1966: it shows the building at night: dramatically shadowed on the outside, but enticingly glowing from within.

Above: Shulman’s extensive oeuvre is documented in a three-volume monograph published by Taschen. Below: One of Shulman’s photographs of Rudolph’s Temple Street Parking Garage. © J. Paul Getty Trust. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2004.R.10)

JULIUS SHULMAN

(1910-2009) Shulman was an almost exact contemporary of some of the other legendary architectural photographers on this list (i.e.: Stoller and Kidder Smith), and his professional career extended over 7 decades—from the 1930’s into the 2000’s. The body of work for which he is most well known is the large set of photographs he took of Modern architecture in California—centered in Los Angeles, but extending to cover buildings in other parts of the state. His clients included some of the most famous makers of Modern architecture: Pierre Koenig (for whom he took a night time photo of the Stalh House which became the iconic emblem of modern living in Southern California,) Neutra, Wright, Soriano, the Eames, and John Lautner. Christopher Hawthorne, of the Los Angeles Times, said of his work: “His famous black-and-white photographs. . . .were not just, as [Thomas] Hines noted, marked by clarity and high contrast. They were also carried aloft by a certain airiness of spirit, a lively confidence that announced that Los Angeles was the place where architecture was being sharpened and throwing off sparks from its daily contact with the cutting edge.” Shulman also had commissions in other parts of the country, as in: his photographs of Lever House in New York, a house by Paolo Soleri in Arizona, and work by Mies in Chicago—and he worked internationally, for example: photographing a residence by Lautner in Mexico. He authored 7 books, participated in 10 others, and his extensive archive is in the Getty Research Institute.

SHULMAN AND PAUL RUDOLPH: While Julius Shulman is identified with the photography of key examples of architectural Modernism in California, he also took assignments for other locations, and his images of Paul Rudolph’s works in New Haven are strong examples of Shulman’s image making. Several can be seen on the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation’s project pages for the Temple Street Parking Garage, and the Yale Married Students Housing. The photographs of the garage are intense with visual drama, highlighting its scale and sculptural qualities.

Above: Molitor’s photo of UMass Dartmouth. Below: Niagara Falls Central Library. Images courtesy of Columbia University, Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Joseph W. Molitor Photograph Collection

JOSEPH W. MOLITOR

(1907-1996) We are fortunate that the the Joseph W. Molitor Photograph Collection is now part of the Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, where it is made available to scholars, researchers, writers, and students. The Avery Library describes Molitor and his career: “Joseph Molitor, recognized as a peer of such leading 20th-century American architectural photographers as Hedrich-Blessing, Balthazar Korab, Julius Shulman, and Ezra Stoller, documented the work of regional and national architects for fifty years. Trained as an architect, he practiced for twelve years before briefly working in advertising. Molitor turned exclusively to architectural photography in the late 1940s, maintaining his studio in suburban Westchester County, New York. Working primarily in black and white, Molitor's images appeared in Architectural Record, The New York Times, House & Home, and other national and international publications.”

MOLITOR AND PAUL RUDOLPH: Avery’s text also mentions “His iconic photograph of a walkway at architect Paul Rudolph’s high school in Sarasota, Florida, won first place in the black and white section of the American Institute of Architects’ architectural photography awards in 1960.” You can find Joseph Molitor’s photographs on several of the project pages within the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation’s website, including the pages devoted to the Milam Residence in Florida, and the Niagara Falls Central Library—and his book, Architectural Photography, published in 1976, features an abundance of images of Rudolph’s work. Recently, the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation has been focused upon Molitor’s work because of the endlessly intriguing set of photographs he made of the Burroughs Wellcome building—showing them with a crispness and sense of drama that few other photographers have approached.

Above and Below: two of Henry L. Kamphoefner’s photographs of interiors within the Burroughs Wellcome building in North Carolina—both images displaying the striking geometries which Rudolph used in the design.

HENRY L. KAMPHOEFNER

(1907-1990) Unlike the above figures, Henry Leveke Kamphoefner is not primarily known as an architectural photographer—but he was well-known in the South as a champion of Modern architecture, especially in North Carolina. Graduating from the Univ. of Illinois with a BS degree in architecture in 1930, in the following years he received a MS in architecture from Columbia and a Certificate of Architecture from the Beaux Arts Institute of Design in New York. From 1932 until 1936, he practiced architecture privately, and one of his most well-known works is a municipal bandshell Sioux City (which was selected by the Royal Institute of British Architects as one of "America's Outstanding Buildings of the Post-War Period.") In 1936 and 1937, he worked as an associate architect for the Rural Resettlement Administration, and during summers after that he was was employed as an architect for the US Navy. He had an ongoing and significant involvement with architectural education: in 1937 he became a professor at the Univ. of Oklahoma and during 1947 was also a visiting professor at the Univ. of Michigan. In 1948 Kamphoefner became the first dean of the North Carolina State College School of Design, creating strict admissions policies and instituting a distinguished visitors program which brought in architects such as Frank Lloyd Wright. He remained dean until 1973, but continued teaching until 1979. From 1979 to 1981 he served as a distinguished visiting professor at Meredith College. Kamphoefner’s importance has been highlighted in a new book, Triangle Modern Architecture, by Victoria Ballard Bell.

KAMPHOEFNER AND PAUL RUDOLPH: The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation has included several of Kamphoefner’s photographs of the Burroughs Wellcome US headquarters and research center on its project page for that building. It is natural that, as a resident of North Carolina, and as an advocate for Modern architecture, that he would be focused on that building. His photographs of the interiors highlight the striking diagonal geometries that Paul Rudolph incorporated into the project. We have included his images of Burroughs Wellcome in several of our blog articles, as part of our fight to preserve this great work of architecture.

COMING SOON: PART TWO

Be sure to look for PART TWO of this study of Paul Rudolph And His Architectural Photographers. It which will look the more recently active photographers, each of whom have focused on the work of Paul Rudolph.