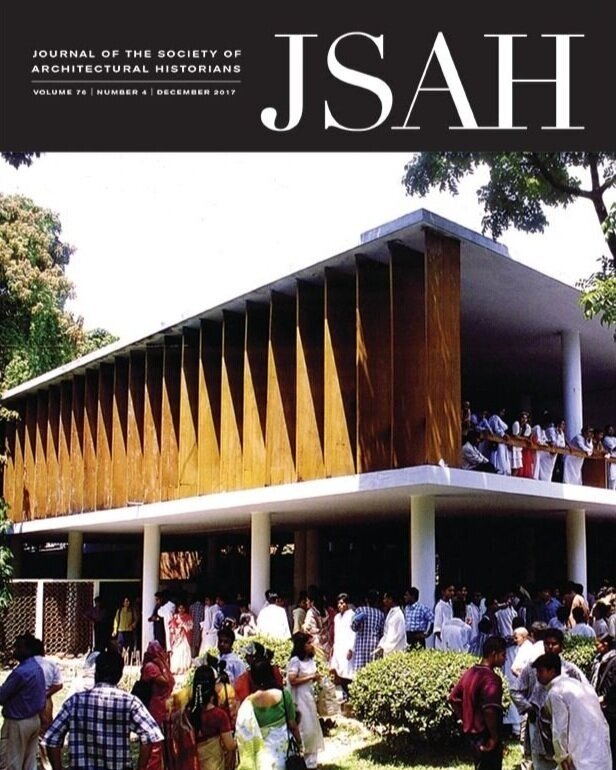

Inspiration can be found anywhere—and the designers of this new, concrete-encased expresso maker have expressed admiration for the work of Paul Rudolph. Like Rudolph’s Yale Art & Architecture building, their design uses contrasting materials & finishes—each of which helps enhance the presence of the others.

Rudolph’s Yale Art & Architecture Building is a design which can be characterized in many ways—and one of them is that the building is a celebration of concrete’s multiple potentials, both in form and texture.

NEW ADVENTURES IN CONCRETE

In recent years we’ve seen an outpouring of new uses for concrete—including for functions and places where it was never expected to go: jewelry, watches, desk accessories, toys, a prototype model for an airplane—and even in candles and cologne (both of which claim to integrate the spirit of concrete into their aromas.)

Concrete jewelry, and…

a concrete watch, and…

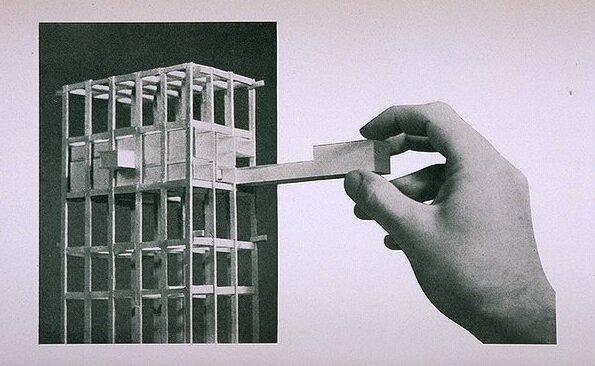

toy blocks, and…

a concrete candle!

But within Kitchens, other than for surfaces (countertops or floors), we’ve never seen concrete used in any way for food preparation. Until now—

AnZa is a small-but-enterprising, California-based company (founded by a designer.) They have an intriguing approach to the use of materials—and their unusual choices caught our eye in the form their prime product: an Espresso Maker.

Here are some photos of AnZa’s concrete incarnation of their expresso machine:

As you can see in this wonderful object, concrete has finally made it into the realm of food preparation. We are delighted that Anza has taken this unexpected plunge into bringing together what must—up-until-now—have seemed the most unlikely pairing of function and material.

AnZa’s designers—Per Selvaag and Andrew Smith—used a range of unexpected materials (for an espresso maker): concrete, Corian, porcelain, brass, and wood, and Anza’s stated aim is to “. . . .deliver a machine as functional as it is aesthetically innovative. A sculptural fixture on any countertop…”

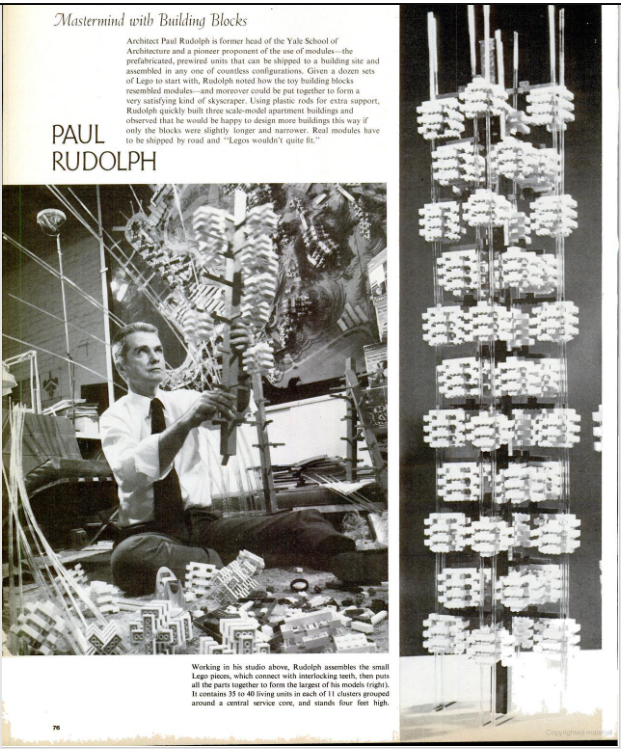

But let Andrew Smith speak tell us a bit more. When we asked him if he was aware of Rudolph’s work, he responded:

“This is amazing! Love Paul Rudolph’s work. . . .I have been aware of Rudolph since I studied design in the early 90s. I have a bit of fascination with concrete. Sverre Fehn + Lautner + Calatrava stand out for me.”

A MATERIAL VISION

He explained their design intent for using concrete:

“We wanted to provide a more human welcoming interaction than is available with a stainless steel / metal espresso machine. We want imperfection in the surface, we want the machine to emit a gentle heat when it's working, for it to have presence and the owners to admit they made a different choice to the pragmatic default.”

They further state about their choice of materials:

“AnZa Concrete is the opposite of bent stainless steel. It’s not shiny, precise, or smooth. It’s matte, rough, organic, and heavy. The precision of the ceramic steam knob and portafilter handle complement the concrete. You won’t find your usual black plastic knobs here.”

After offering the espresso maker in two versions—concrete -or- a smooth, white Corian—he also mentioned their surprise:

Anza’s alternative design for the espresso maker: it is beautifully made in smooth Corian, but—to their surprise—it was less popular than the concrete version.

“We made a machine out of white Corian as we thought no one would buy a concrete espresso machine. The Concrete machine has outsold the Corian machine especially in Europe, so maybe people are less pragmatic and more romantic than we thought?”

In case one is worried about this “more romantic” approach to the selection of materials—in this case, concrete—Anza gives supplementary data on its use and care. Included among the information they provide is the following point:

“The concrete shell has been treated with a sealer to protect the surface. Due to its rough and porous surface the concrete will naturally develop a patina over time which will be impossible to prevent or remove. Wiping down areas of the shell which are in contact with coffee grounds and water will reduce the build up of patina.”

Having coffee with Rudolph, or your favorite architectural aficionado? Or rather: something stronger—espresso! Then we can’t imagine a more appropriate way to obtain it than from this strikingly designed, concrete expresso maker.

IMAGE CREDITS

NOTES:

The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation gratefully thanks all the individuals and organizations whose images are used in this non-profit scholarly and educational project.

The credits are shown when known to us, and are to the best of our knowledge, but the origin and connected rights of many images (especially vintage photos and other vintage materials) are often difficult determine. In all cases the materials are used in-good faith, and in fair use, in our non-profit, scholarly, and educational efforts. If any use, credits, or rights need to be amended or changed, please let us know.

When/If Wikimedia Commons links are provided, they are linked to the information page for that particular image. Information about the rights for the use of each of those images, as well as technical information on the images, can be found on those individual pages.

CREDITS:

All images of the AnZa espresso machines: courtesy of AnZa; Yale Art & Architecture Building: photo by G. E. Kidder Smith, courtesy of and © the Massachusetts Institute of Technology; Images of concrete jewelry, watch, toy, and candle: see previous blog posts about alternative uses of concrete.

![A chart from the Pew Research Center’s study of Public Trust in Government: 1958-2019 The overall downward trend, from 1964 to the present, is evident. [Note that the largest and steepest drop was in the wake of the mid-1970’s Watergate scandal.] Wh…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a75ee0949fc2bc37b3ffb97/1616438220772-C9X7PWXIHIW0L7MK9ZX1/trust%2Bin%2Bgovt.jpg)