Saarinen’s “Tulip Chair”—part of the “Pedestal Group” of furniture which included designs for tables and other forms of seating. These designs—these objects—became icons of Modern design in the Mid-20th Century.

Saarinen’s St. Louis Gateway Arch—the winner of a design competition held in 1947. A feat of design, engineering, and construction, it is sheathed in stainless-steel and was completed in 1965, rising to 630 feet.

EERO SAARINEN (August 20. 1910 - September 1, 1961)

This week, we celebrate the birthday of a profound shaper of Modern Architecture:

EERO SAARINEN

EERO SAARINEN (Aug. 20. 1910 - Sept. 1, 1961) was a creator at every scale—an architect concerned with all aspects of a design, from the most subtle shaping of a mullion -to- the overall form of a national monument -to- the user experience of airline passengers -to- the planning of entire academic, research, and corporate campuses.

At one end of the scale: his furniture—as exemplified by the Tulip Chair (part of the “Pedestal Series”, shown above)—was not only practical and comfortable, but also became iconic in creating the Modern interior.

At the other end of the scale: he was unparalleled in his ability to create shapes that were meaningful and appropriate for each challenge—-often expressing the spirit of an energetic, optimistic, upward-bound, “can do” era of America. This is reflected in the Gateway Arch-Jefferson Expansion National Memorial (above), and his TWA Flight Center in New York and Washington Dulles International Airport (both below).

Eero Saarinen’s TWA Flight Center, the airline’s terminal at JFK Airport: even when under construction—as shown here—it shows the drama of it’s conception.

Dulles International Airport—the main airport for Washington. Here too, one can see his skill at creating forms and spaces which combine function and drama.

The skylit interior of the Chapel at MIT. The suspended metal screen behind the altar is by Harry Bertoia (1915-1978), a prominent artist and furniture designer.

Yet for projects that would be better served by a different level of formal and spatial energy, Saarinen was just as adept at creating environments of a quieter kind, evoking reverence and serenity—and his Chapel at MIT would be a prime example. Further—to the extent that research can be a contemplative activity—this could said to be true of the several corporate research centers designed for Bell Labs, General Motors, and IBM.

The buildings mentioned are among Eero Saarinen’s “greatest hits”—the ones for which he is most well-known (the quality of work whose character got him on the cover of TIME Magazine in 1956).

Eero Saarinen died unexpectedly young: he was only 51—and it is interesting to speculate what Saarinen would have produced if he’d been able to practice for two-or-three additional decades. Some architecture critics complained about his fluid and mutable approach to solving design challenges (a quality that is also manifest in the work of a number of creative architects, from John Nash -to- Bruce Goff -to- Paul Rudolph). But in essence what they said was true: Saarinen could never quite be pinned-down to a particular “style”. So we can’t say what he’d have produced—but, we could predict that (had he a another two-dozen years to work) he would have created many more memorable designs.

SAARINEN’S FINAL DESIGN ?

For Eero Saarinen, the project is an airport terminal—his final one: a large facility for Athens, Greece. He was already quite famous for his other airport designs—TWA and Dulles. Yet this project is one of his least-known—and that is strangely so, as it was a sizable building, on a prominent site, and one which was completed and in full use for several decades.

ELLINIKON INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT

Ellinikon (or Hellinikon) International Airport was originally built in 1938, and for 63 years served as the major airport of Athens (being later replaced by the the new Athens International Airport). It was a busy complex: just before the airport’s 2001 closure, it had recorded a 15.6% growth rate over its previous year, serving 13.5 million passengers per year and handled 57 airlines flying to 87 destinations.

An aerial view of the airport, with Mount Hymettus in background. Saarinen designed one of the airport’s two terminals.

The airport had two terminals: the West Terminal for Olympic Airways; and the East Terminal for all other carriers. The East Terminal building was designed by Eero Saarinen (just before his unexpected passing in 1961), and it opened in 1969.

SAARINEN: ON THE WAY TO A DESIGN

Saarinen’s proposed design was covered by major architectural magazines. But, before looking at Saarinen’s presentation model and drawings, it’s worth considering his thinking as revealed in his sketches. Below are several that are in the collection of the Canadian Centre for Architecture (the CCA), and they show some of the directions which Saarinen was exploring.

The Canadian Centre for Architecture (the CCA) has a collection of drawings by Saarinen and his office, illustrating the development of several of his projects. Above is a screen-grab from their web-page which shows some of their Saarinen drawings for the Athens Airport. At the lower-left is his sketch of the Parthenon—showing, we suspect, part of his process by which Saarinen was attempting to assimilate the spirit of the country’s most famous building. In the center (upper and lower) are drawings whose sectional profiles are reminiscent of the silhouette of Saarinen’s Dulles Airport—-though the Athens sections show an interior development that is different from the “one room” space of Dulles. The upper-left drawing and the ones at the right (upper and lower), and some of the sketches in the upper-center drawing, show a columnar rhythm that is resonant with the spirit of the Greek temple colonnades. Of this set of sketches, the top-most drawing, at the upper-left, is closest to the airport building’s final design.

A sketch by Eero Saarinen for the Athens airport terminal—done on yellow legal pad paper—a design is close to the final version of the building.

Architects are frequent owners of sketchbooks - but when an architect is suddenly inspired, or needs to quickly communicate their idea to another person, sometimes they’ll grab any paper at hand. [The archive of the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation has examples of Rudolph doing just that: we’ve found sketches on every kind of paper and document.].

In books on Eero Saarinen, it is interesting to come across his first sketch of the TWA terminal—drawn on a menu. The design sketch for Yale’s Ingalls Hockey Rink is even more well known: not only for its sweeping curved lines (which were carried-over to the building’s final design)—but also for the medium: it was sketched on a piece of yellow legal-pad paper. Perhaps that was one of Saarinen’s favorite mediums, for it also served for one of his sketches for the Athens airport terminal (shown at right)—and this sketch is very close to the design that was used for presentation drawings and models.

THE PREVALENCE OF A PARTI

Eero Saarinen was not alone in using this type of composition. Nor was he the only one to turn-to regularly-spaced rows of columns to give a building a sense of classical dignity. In the very same August 1962 issue of Architectural Record (in which Saarinen’s Athens terminal appeared) there was a news story about Minoru Yamasaki’s design for the Woodrow Wilson School building, to be built on the Princeton University campus.

The Woodrow Wilson School building (Robertson Hall) for Princeton University, by Minoru Yamasaki—as it appeared in a news story in the same issue of Architectural Record as the article on Saarinen’s Athens terminal design.

The similarities between the two building concepts are striking. This “Colonnade and Roof” (or “Colonnade and Attic”) combination was named, remarked upon, and illustrated in Arthur Drexler’s 1979 Museum of Modern Art exhibition and book: “Transformations In Modern Architecture.” Drexler showed two pages of examples, including the Wilson School (and you can find a copy the full catalog here.)

Both Saarinen and Yamasaki (and the others whose work Drexler showed) were turning to a classic parti which they knew had the power to express what they felt was appropriate to the building’s type and context. This composition’s use in Yamasaki’s project sought to evoke the dignity of government and be sensitive to the vintage campus setting; its use in Saarinen’s project resonated with Greece’s architectural heritage—and Saarinen specifically referenced that when describing his design.

THE DESIGN AS PRESENTED

The August 1962 issues of both Progressive Architecture and Architectural Record had articles about the design. Both articles described the building’s goals, strategies for handling practical aspects of this kind of project (especially circulation), key statistics, and the architect’s intentions—and were illustrated by images of the model, as well as plan, section and rendering drawings.

Progressive Architecture’s coverage of the Athens terminal design led-off with a photo of the model.

Architectural Record’s opening of their coverage included quotes from Eero Saarinen on his goals for the project.

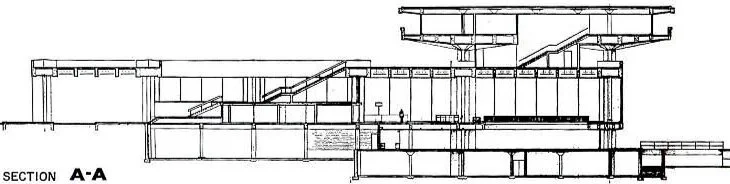

A longitudinal section through the building. From the land, passengers would arrive on the Left (driving through and stopping under a covered area.) The air field would be toward the Right. The large, cantilevered portion of the building (it’s slab-like “hat” volume, which provides protective shade for the areas below) is at the Upper-Right.

The following passages are from the two articles, and from the architect:

Two more views of the Athens terminal architectural model, produced by Saarinen’s team. TOP: The building as seen from the land side (roadways for arriving and departing cars are in the foreground). BOTTOM: a view of the building as seen from the airfield.

From Architectural Record:

The final design for the terminal building for Athens Airport was presented to the Greek Government by Eero Saarinen in May 1961, less than four months before his death on September 1, and was accepted. . . .

In form, the terminal building is essentially two boxes, directly expressing the interior volumes ; the lower one (260 ft long by 240 ft wide by 20 ft high) contains all functions concerned with arrivals and departures and passenger handling; the upper one (250 ft long by 120 ft wide by 10 ft high) cantilevers out above the main block 22 ft in three directions and contains public and transit passenger restaurants ·and airline and government offices.

And from Progressive Architecture:

A third dramatic air terminal will be added to the late Eero Saarinen's collection, which already includes TWA Terminal in New York and Dulles Terminal in Washington. At the time he died, Saarinen was working on a new airport for Athens, which, he said, gave him "the challenge of creating a building which would belong proudly to the 20th Century, but would simultaneously respect and reflect the glorious tradition of Greek architecture."

The terminal will be a stately building of concrete with pantellic marble aggregate, recalling the white buildings of an earlier Greece. . . .

Structurally, hollow beams will hang from cruciform-shaped columns. They will also serve for air circulation. The columns will penetrate the slab and their capitals will return to pick up the beam. The columns on the field side extend up and branch out to carry the cantilevered section.

And from Eero Saarinen himself:

“In contrast to many airports in which the high façade and monumental entrance face the city, this building faces the field. The majority of arriving visitors will approach it along beautifully landscaped terraces, instead of in enclosed fingers-an advantage due to the special, virtually rainless climate of Greece.”

”The form of the building grows out of its site. Whereas the site slopes grandly down from Mount Hymettus to the Bay of Saronikos, the dominant form of the building is a dramatic counter-thrust upward. Thus, the deep cantilevers over the sheer walls on the field side (cantilevers which, incidentally, will also make a huge shadow to help protect the windows of the field façade from the afternoon sun).”

”Post and lintel construction is characteristic of ancient marble buildings of Greece; this post and beam construction developed into long spans with daring cantilevers is natural to concrete and to our time. Built of concrete with Pentelic marble aggregate, which becomes a very beautiful material, the building will have the shimmering white texture which looks so magnificent in the Greek landscape.”

An interior perspective rendering—probably in ink, watercolor, and gouache—of the Second Floor. Passengers and visitors could promenade around a large opening in the floor, which looked down upon the Ground Floor waiting area. A large stair (the top of which is shown at the lower-right) allows travel between the two levels. The promenade was to have views of the airfield (which is primarily to the right) though large windows on three sides. [Floor plans, showing the relationship between these two levels of the terminal building, are below.]

The Ground Floor Plan of the main part Saarinen’s Ellinikon International Airport building. The waiting area is at the bottom-center of the drawing, and the airfield would be below that. The upper two-thirds of the drawing show accommodation for other facilities necessary to terminal operations.

The Second Floor Plan of the main part of the terminal. The promenade is toward the bottom of the drawing, and the opening in the floor (which looks-down upon the Ground Floor seating area) is the white rectangle in the bottom-center). At the left side of that opening is the stairway between the two levels.

BUILT—AND ACTIVE

Completion was originally projected for 1964, but took a half-decade more before the terminal opened in 1969. The airport was busy—and, over more than three-decades, multiple-millions of passengers flowed through its facilities.

Eero Saarinen’s airport terminal for Athens: it is worth comparing this as-built view with Saarinen’s early design sketches, as well as the presentation drawings (shown earlier in this article).

A view of the land side of the terminal, at which passengers would arrive and depart by automobile. The airfield is on the other side of the building.

The busy interior of the Ground Floor’s waiting area. At the rear is the grand stair which connects this level to the Second Floor’s promenade area above.

ABANDONMENT—AND POSSIBLE FUTURES

Ellinikon International Airport was closed in 2001—and the terminal buildings were largely abandoned, presenting sad views of architecture that was un-cared for. There were several plans for using the site, and one of them is Hellenikon Metropolitan Park. That development would encompass a park, luxury homes, hotels, a casino, a marina, shops, offices and would include Greece's tallest buildings.

By contrast, there are counter-proposals for a less commercially-focused use of the site and surrounding urban areas, and planning based on alternative ecological, economic, and social models. An organization, Recentering Periphery, has a web page on Ellinikon airport which shows its abandoned state (including the below view of Saarinen’s terminal building), and then offers information leading to re-imagining a different future for area.

The airport closed in 2001, and the facilities were largely abandoned. This view shows the terminal in it’s un-used state.

The un-used terminal—this view showing the interior from Second Floor promenade, looking down to the Ground Floor waiting area. [The airfield would be on the right.]. This is the same view as the shown in the rendering, earlier in this article—and, even in this abandoned state, one can sense the grandeur of the space. Some plans for the site speak of adaptive=reuse and renovation of the building—and one can imagine the possibilities for this dynamic space.

The works of all architects—no matter their level of fame, or their high valuation in architectural history—are subject to danger. Eero Saarinen’s only skyscraper, the CBS Building in New York—a refined example of Modern high-rise building design—has just been sold. Will the new owners be good stewards of this celebrated work of architecture? What will be it’s future?

The same questions apply in Athens—and, allegedly, some plans for the site include renovation and adaptive reuse of the Saarinen-designed terminal building.

AS WE CELEBRATE SAARINEN’S BIRTHDAY, WE HOPE THAT THIS PROJECT—ONE OF HIS LAST DESIGNS, AND A LANDMARK OF MODERN ARCHITECTURE IN GREECE—WILL BE PRESERVED.

IMAGE CREDITS

NOTES:

The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation gratefully thanks all the individuals and organizations whose images are used in this non-profit scholarly and educational project.

The credits are shown when known to us, and are to the best of our knowledge, but the origin and connected rights of many images (especially vintage photos and other vintage materials) are often difficult determine. In all cases the materials are used in-good faith, and in fair use, in our non-profit, scholarly, and educational efforts. If any use, credits, or rights need to be amended or changed, please let us know.

When/If Wikimedia Commons links are provided, they are linked to the information page for that particular image. Information about the rights for the use of each of those images, as well as technical information on the images, can be found on those individual pages.

CREDITS, FROM LEFT-TO-RIGHT and TOP-TO-BOTTOM:

Tulip Chair, designed by Saarinen: photo from Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal, via Wikimedia Commons; Gateway Arch, designed by Saarinen: photo by Chris English, via Wikimedia Commons; Photo portrait of Eero Saarinen: photo by Balthazar Korab, via Wikimedia Commons; TWA Flight Center, designed by Saarinen: photo by Balthazar Korab, via Wikimedia Commons; Dulles Airport, designed by Saarinen: photo by Carol M. Highsmith, via Wikimedia Commons; MIT Chapel interior, designed by Saarinen: photo by Daderot, via Wikimedia Commons; Aerial view of Ellinikon airport: photo by Konstantin von Wedelstaedt, via Wikimedia Commons; Saarinen sketches for Athens airport: screen capture from the website of the Canadian Centre for Architecture; Saarinen sketch on yellow legal pad, for Athens airport, and news stories about Yamasaki’s Princeton Woodrow Wilson School and on Saarinen’s Athens airport (including photos of model and the drawings): from Issues of Progressive Architecture and Architectural Record via US Modernist Library; Vintage views of Athens airport: via Pinterest and Internet Archive; View of abandoned Athens airport terminal: from the website of Recentering Periperhry

![An interior perspective rendering—probably in ink, watercolor, and gouache—of the Second Floor. Passengers and visitors could promenade around a large opening in the floor, which looked down upon the Ground Floor waiting area. A large stair (the top of which is shown at the lower-right) allows travel between the two levels. The promenade was to have views of the airfield (which is primarily to the right) though large windows on three sides. [Floor plans, showing the relationship between these two levels of the terminal building, are below.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a75ee0949fc2bc37b3ffb97/1629226814988-X9TXRA94FZWG3D0XI60K/interior%2Brendering.jpg)

![The un-used terminal—this view showing the interior from Second Floor promenade, looking down to the Ground Floor waiting area. [The airfield would be on the right.]. This is the same view as the shown in the rendering, earlier in this article—and, even in this abandoned state, one can sense the grandeur of the space. Some plans for the site speak of adaptive=reuse and renovation of the building—and one can imagine the possibilities for this dynamic space.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a75ee0949fc2bc37b3ffb97/1629233432432-A5RCLXI14R5EL2L6GU2D/pintarest+interior.jpg)