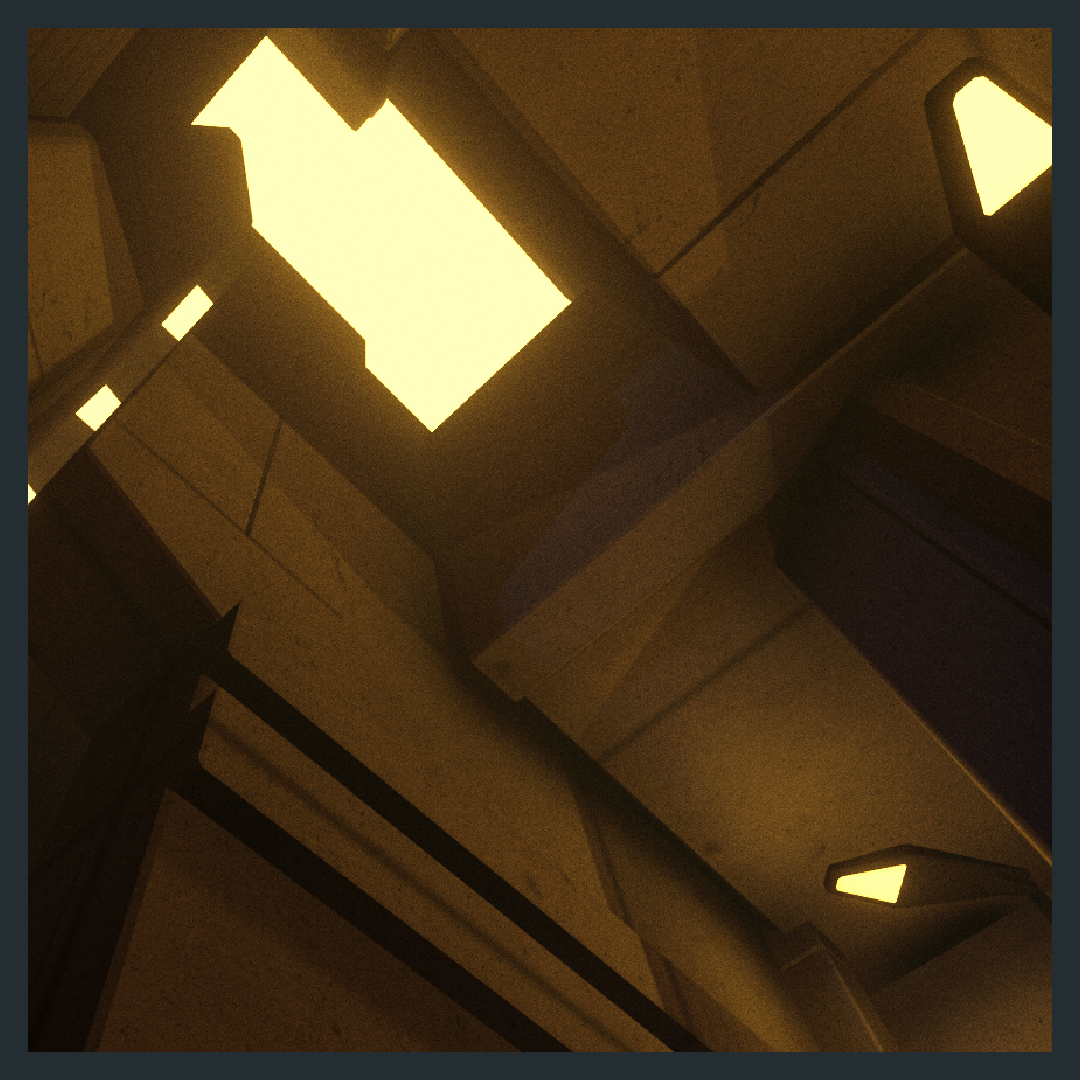

Paul Rudolph’s Umbrella residence in 2018. Photo: Kelvin Dickinson, Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation Archives

As with Paul Rudolph’s Cocoon House, Sarasota High School, and Sanderling Beach Club, Harold Bubil—the distinguished Real Estate Editor Emeritus for Sarasota’s Herald-Tribune—has put Rudolph’s Umbrella House on his list of “Florida Buildings I Love.”

And with good reason, as the 1953 building (which has been nominated to be on the National Register of Historic Places) embraces so many still fresh architectural ideas, and was executed with economical elegance.

An Amazing Client

Philip Hiss was an extraordinary and endlessly energic character: adventurer, writer, photographer, developer, educator, traveler (with an eye to anthropology and indigenous building solutions)—and a discerning patron of Modern architecture. His own library-studio, designed by Tim Siebert in 1953, was also a local (and very Modern) landmark: a cleanly rectilinear volume, using modern construction materials, raised on a steel structure. It even included the innovation of air conditioning (to protect Hiss’ book collection)—an unusual (and, for the time, pricey) feature.

The Architect

When developing the Lido Shores neighborhood in Sarasota, Hiss chose Paul Rudolph to design the flagship home: the Umbrella House.

Pearl Harbor happened very shortly after Rudolph began his graduate architecture studies at Harvard (under the famous former director of the Bauhaus, Walter Gropius), and Rudolph (and his cohort of classmates) enlisted. Rudolph became a U.S. Navy officer, stationed at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, where he learned important lessons on construction, materials, organization, and even the style of command—a body of knowledge that was to serve him for the rest of his career. Rudolph’s adventurous & innovative use of materials—perhaps seeded by his experience of maritime construction—can be repeatedly seen n his Florida work.

After the war, Rudolph returned to for his degree. Harvard was among a number of design programs which created accelerated programs for veterans, and Rudolph was able to graduate in less than a year. Moving to Florida (which he had been told was a place of opportunity for architects), his career really got started in the Sarasota area in the mid-1940’s (tho’ he eventually did work in several parts of Florida.)

Philp Hiss had good grounds for selecting Paul Rudolph as his architect:

in the approximate half-decade since starting practice in Florida, Rudolph had already built an impressive number of houses

even though the design of his houses had a fresh and Modern feel, such construction was not necessarily more expensive: Rudolph had shown the practical ability to build on a budget

Hiss, from his wide travels - especially to tropical environments - had developed definite ideas about how to build for hot climates - and Rudolph’s designs were simpatico to Hiss’ concerns and requirements

Modern Character (and Innovations) in the Umbrella House’s Design

Modern architecture has been much derided (sometimes with good reason) for its endless proliferation of banal & characterless container-like buildings - or as those productions are dubbed, the “Harvard Box.” Even though Rudolph was educated, at Harvard, by Gropius - the very fountainhead of that boxy approach - you could never say that a Rudolph building is boring! Here, at the Umbrella House, he brought his always inventive-yet-practical creativity to the design of this home.

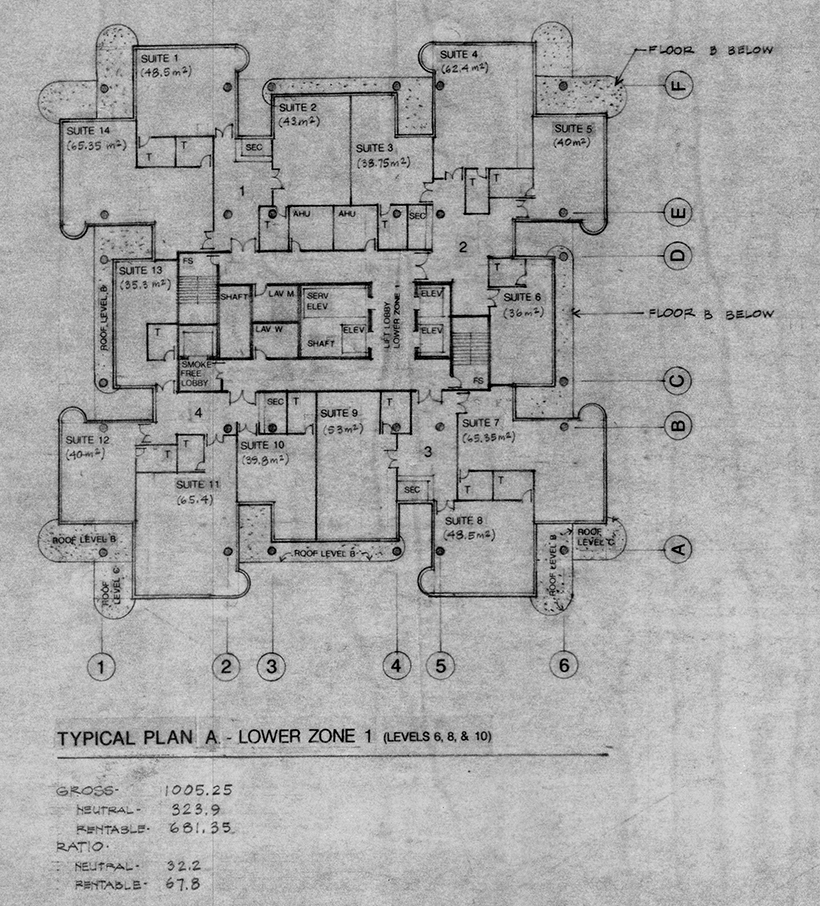

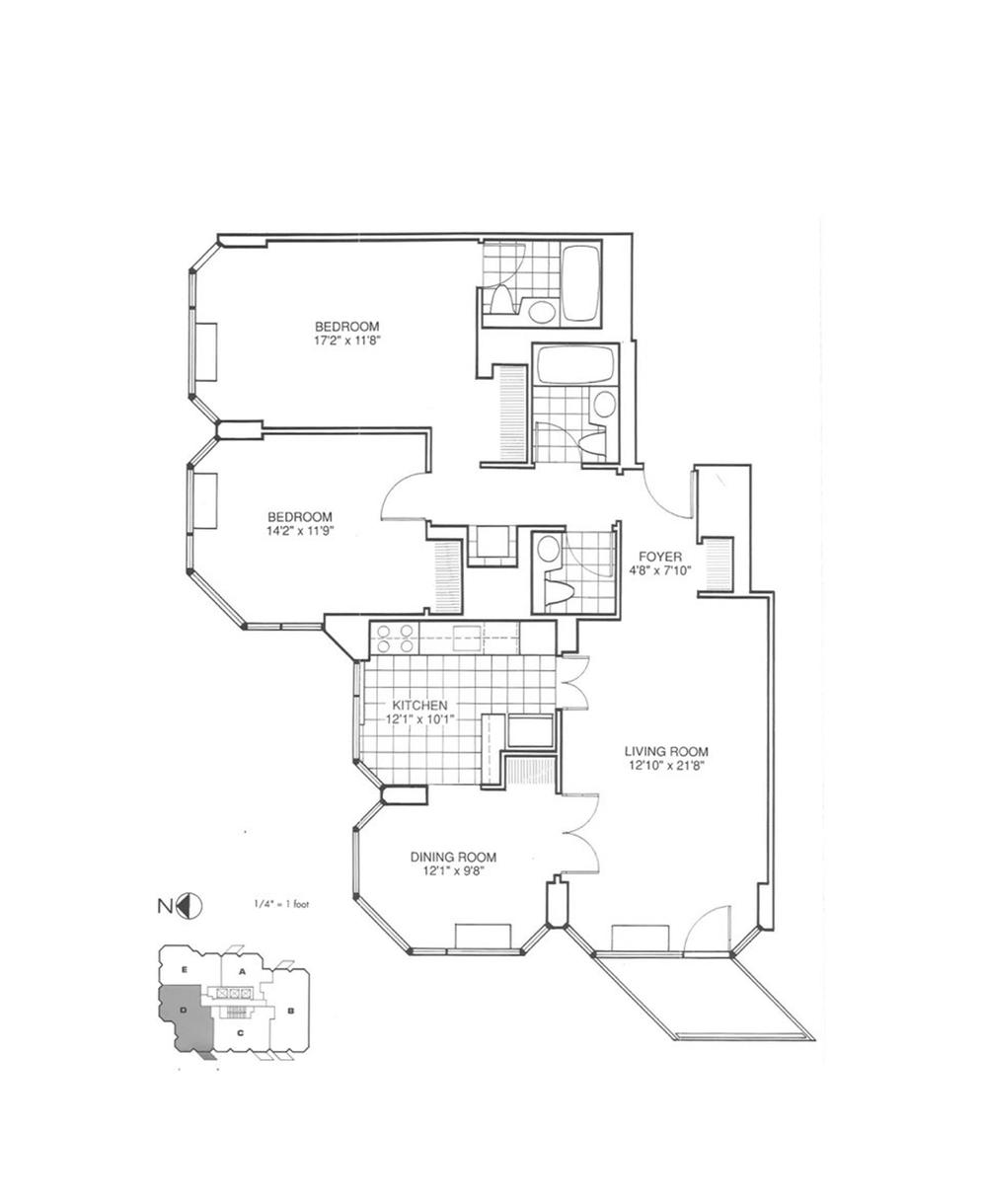

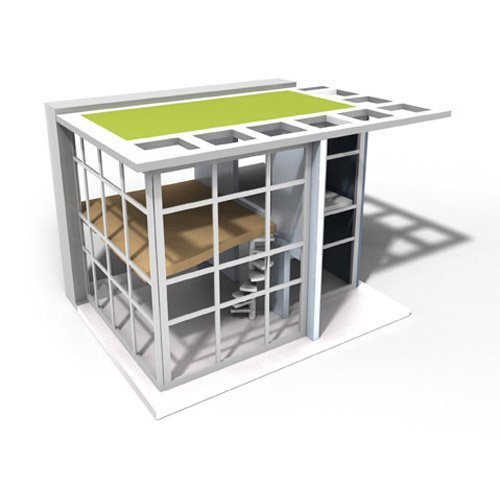

Ground Floor Plan. Image: Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation Archives

First Floor Plan. Image: Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation Archives

Some of its design features include:

One of the most intractable problems of building design in hot and sunny climates is the solar heat-load on the roof. Covering the building’s entire area, the roof becomes a giant solar heat “magnet.” Even the best-insulated roof can only ameliorate the problem to a rather limited extent—and any mitigation is further reduced when the whole environment is hot (“Florida hot!”) day-after-day. One solution - very effective, but rarely tried - is a roof-over-a-roof: the upper roof blocks the sun, and a lower roof - well-separated by air-space, and shaded from above - is the actual enclosure of the house. Rudolph went far in the direction of this approach by erecting a large, trellis-like structure over the entire house (living volume, pool, and deck) - an “umbrella” - thus giving the house its famous name.

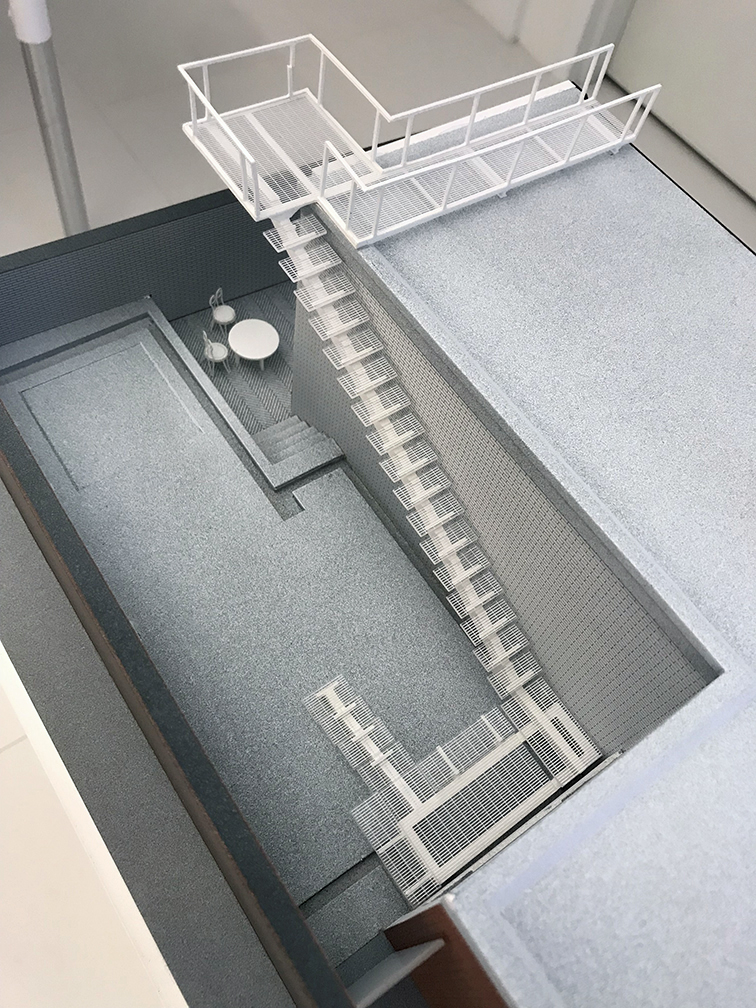

Side Elevation. Image: Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation Archives

Rudolph raised the volume (enclosing the interior living spaces) above the ground plane. Not only did this separate the body of the house from ground-borne moisture, but it also reinforced the visual purity of the architecture: the main component of the house—the one that defined the interiors—seemed to float, and the volume’s edges were well-defined by the shadow-line at its bottom.

Pool-side Elevation. Image: Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation Archives

Most architects, when designing, primarily focus on the plan (and then the elevations). But Paul Rudolph thought in section—something that even his colleagues jealously admit is rare among architects. His orientation to sectional analysis led him to creating spaces with a profound variety of ceiling heights—and his ability to manipulate space allowed him to create the two major kinds of environments that people like to occupy: large, open spaces (which Rudolph characterized as “the fishbowl”) and enclosed, snug spaces (which he called “the cave”). The height of the Umbrella House was the canvas within which he could compose such spatial experiences. The double-height living room was airy and commodious—but, tucked beneath the stairs, was the Florida incarnation of a fireplace inglenook for reading and cozy conversation.

Even though the entire house—including pool and its deck—was under the roof’s trellis-like shade, Rudolph provided a particularly protected sitting area (at the far end of the pool): this is a lowered, solid roof, which not only offered definitive blocking to the sun, but also fulfilled the occupants’ psychological needs for a well-defined seating area.

Preservation

In the mid-1960’s, the house suffered some hurricane damage, and in the subsequent decades it came into a state of disrepair. In 2005 it was partially restored---and then later sold, and restored by Hall Architects (for which it won several outstanding awards for preservation.)

Christopher J. Berger did an extensive thesis about the challenges of preserving works of the “Sarasota School”—and one of the buildings he focused-upon is the Umbrella house. You can see his full, well-researched thesis—which includes extensive historical context on building in Sarasota, and the fascinating cast-of-characters involved—here: http://etd.fcla.edu/UF/UFE0041751/berger_c.pdf

City Recognition—and National Register Nomination

The Umbrella House has been designated as an historic landmark of the City of Sarasota.

Photo: Kelvin Dickinson, Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation Archives

David Conway—deputy managing editor of the Sarasota-based YourObserver.com—writes that the Umbrella House is a “a defining work of the Sarasota School of Architecture,” and reports:

Backed by the state Bureau of Historic Preservation, the Umbrella House has been nominated for a slot on the National Register of Historic Places. The two-story home in Lido Shores, designed by Paul Rudolph and built in 1953, is frequently cited as one of the standout works from the midcentury Sarasota School of Architecture movement.

Although dozens of structures within the city are listed on the National Register of Historic Places, most of them date to previous waves of development in the early 1900s. The Umbrella House is set to become one of the few Sarasota School works on the National Register, joining the Rudolph-designed Sarasota High School addition and the Scott Building at 265 S. Orange Ave.

The Umbrella House already has a local historic designation, which offers incentives for rehabilitation and requires city review of proposed changes to the home. In 2015, the Umbrella House was renovated to re-create its namesake “umbrella” structure, designed to shade the residence.

City Planner Cliff Smith said the national designation was another way the property owners are attempting to secure the Umbrella House’s historic legacy. On Tuesday, the city’s Historic Preservation Board voted unanimously to endorse the application, which a national committee will consider in August.

Smith said the designation would add to the significance of an architectural movement in which the community has taken great pride.

“The Sarasota School of Architecture, that unique form of building that’s indigenous to the city of Sarasota — we’re very happy that’s reached national status,” Smith said.