Paul Rudolph’s Boston Government Service Center shows Rudolph’s engagement with art—and it includes another fascinating work of public sculpture.

A Bigger Context for the Boston Government Service Center: The commitment - and tensions - of a government’s relationship with its citizens

Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation issues letter of support for preserving the Boston Government Service Center

Massachusetts Historical Commission weighs in favor of saving Paul Rudolph

Boston Preservation Alliance: Making the case for Re-Investment (not De-Investment) in Rudolph's Boston Government Service Center

DOCOMOMO-New England Calls For Preserving Rudolph's Boston Government Service Center

Archetypes of Space: a Poetic View Into Rudolph's Design for the Boston Government Service Center

New Film Features Paul Rudolph's Boston Government Service Center

Update: Development "Alternatives" Report Released for Rudolph's BOSTON GOVERNMENT SERVICE CENTER

S.O.S. Update # 4 : Proposed Demo & Development at Rudolph's Boston Government Service Center

Paul Rudolph’s original, overall conception for the Boston Government Service Center included a tower (which, unfortunately, was not built). The proposed development of the site brings up a serious question: Would/could new construction be as harmonious (with the existing buildings) as the design Rudolph created? Rendering by Helmut Jacoby. The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

In this developing story, the state of Massachusetts’ Division of Capital Asset Management & Maintenance issued a power point presentation about their redevelopment proposal for the Boston Government Service Center—one of Paul Rudolph’s largest urban civic commissions. We’ve been looking at the various slides in their power point “deck” and examining the various assertions they make—and bringing forth our sincere and serious questions.

In previous posts we’ve looked at the ideas (as shown in their presentation) on the current building, development, how current occupants of the building would be handled, etc… —and offered our concerns about each.

Let’s look at the their next two slides:

WHAT WILL BE DEVELOPED THERE?

Following each of the slide’s points, we offer responses/questions:

The redevelopment partner that the state chooses will be responsible for planning, financing, and permitting the redevelopment.

The key word here is: planning—and we ask: How are they getting input during that process? And from what stakeholders? (and how is it weighted, and who has a veto?)

This process will be subject to Large Development Review by the Boston Planning and Development Agency under Article 80, and to review by MEPA.

It would be useful to all parties to lay this out in more detail, so that all can see what’s involved—and where (at what points) real input and interventions can be offered to improve all proposals.

The site is zoned for more intensive use than is currently realized. – Allowable Floor Area Ratio (FAR) is 8-10 (currently ~2.0).

Ideas about zoning (especially levels of density) change over time, as different planning theories and urban design schools-of-thought become popular and wane. Moreover, the question of desirable density is subject to political pressures. What makes a good building/public space/block/street is not always determined by zoning codes, equations, or the theories of the moment.

Generally, height is limited to 125’ towards the street edges, and up to 400’ on the interior.

Perhaps they’re saying that those are the current code’s height limits, which a developer must work within. It would be useful to know if that is the intent, or if there are other consequences.

Planned Development Areas (PDAs) are allowed on a portion of the site. The redevelopment partner may use the PDA process in order to allow the site to be more thoughtfully planned.

The consequences of this statement are not clear, and it would be useful to know more about PDA’s. The phrase “more thoughtfully planned” begs the question: more than what?

And let’s consider their next slide:

hISTORIC PRESERVATION APPROACH

Following each of this slide’s points, we offer our responses/questions:

DCAMM’s approach to redevelopment will acknowledge the architecturally significant elements of the Hurley-Lindemann site, while addressing its flaws.

The language begs the question about the building having flaws—-whose nature and quantity is unspecified. Any building can probably be renovated over time, and made more congruent with current needs—and we need clarity on what’s claimed and what’s proposed.

The Government Services Center complex was planned by prominent architect Paul Rudolph.

Yes, Paul Rudolph conceived of the overall plan and design: it is one of his major urban-civic buildings.

The complex was meant to include three buildings, but only two of the original buildings were built (Brooke courthouse was added later).

It is unfortunate that the scheme was not fully realized.

The Lindemann Mental Health Center was also designed by Rudolph, and is more architecturally significant than the Hurley building.

This project was designed as a set connected buildings that are strongly related—with a level of coordination in design that would create a feeling of wholeness to the block. That sense of wholeness is fundamental to good architecture—and is something to which Paul Rudolph was committed. Setting-up one building against the other is contrary to the way the complex was conceived and designed—and one can even see this from Rudolph’s earliest sketch.

DCAMM is required to file a Project Notification Form (PNF) with the Massachusetts Historical Commission (MHC). DCAMM will then work with MHC to develop a Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) regarding future development at the site.

It would be useful to know more about this process, how it functions, and how input is received from all interested parties—and, in this case, what ingredients go into creating a Memorandum of Agreement (MOA).

NEXT STEPS: LISTENING AND ACTING

We will continue to respectfully review the state’s proposals—and raise sincere questions when appropriate.

If you have information or insights to contribute, for preserving this important civic building by Paul Rudolph, please let us know at:

office@paulrudolphheritagefoundation.org

Paul Rudolph’s original sketch for the layout of the Boston Government Service Center. The drawing summarizes the overall concept of having the set of strongly related buildings wrapping around the triangular site—with a large, open plaza in the center.. A tower is indicated by the hatched pinwheel-shape toward the middle. © The estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

S.O.S. Update # 3 : Proposed Demo & Development at Rudolph's Boston Government Service Center

The publicly accessible courtyard at the center of of Paul Rudolph’s Boston Government Service Center. While one sometimes hears accusations against the building, it should be equally noted that it is also a public oasis of green and peace. Photo courtesy of UMASS

In this developing story, the state of Massachusetts’ Division of Capital Asset Management & Maintenance has issued a power point deck about their redevelopment proposal; We’ve been looking at the various assertions they put forth—and offering our sincere and serious questions and concerns.

We’ve looked at (and offered our questions about) the first set of their powerpoint slides, and then did so with a second set.

Let’s look at the next two:

PLANS FOR CURRENT BUILDING OCCUPANTS

Following each of the slide’s points, we offer responses/questions:

DCAMM will work with all occupants and relevant union leadership to find temporary and permanent relocation space that suits agency operational needs in a cost-effective way.

With any relocation of multiple departments and numerous staff, the question must be asked: How much disruption to services (and employee lives) will be caused by this? -and- For how long? We understand that promises based on projected timelines are offered in good faith—but often projects are delayed (sometimes for years) by unexpected factors (for example: construction delays, changing budgetary priorities, changes in administrative structure, changes in leadership….) So: however long the relocation/disruption/dislocation has been projected to last, in reality is could go on for much longer.

Current plans entail the majority of EOLWD employees who currently work at the Hurley Building returning to the redeveloped site.

Since the development plans are not even sketched out, on what basis can this promise be made?

No state employees will lose their jobs as a result of this redevelopment.

Same as above: plans are not even known—on what basis can promises be made?

Employees will remain in or near Boston, in transit accessible locations

What’s meant by near and transit accessible needs to be defined.

And let us consider the next slide:

US DEPARTMENT OF LABOR

Following each of this slide’s points, we offer our responses/questions:

The US Department of Labor funded the initial construction and site acquisition of the Hurley Building, and still has a significant amount of equity in the site.

It would be useful to know the extent of the equity, and the tangible consequences of this statement.

As required by federal rules, the Commonwealth is working with USDOL to ensure that federal equity is used to further the work of the Commonwealth’s Labor and Workforce Development agencies.

Here too, it would be useful to have things made more explicit: What rules are being invoked? What federal equity is being referred to? and overall: What are the consequences of this statement?

NEXT STEPS: LISTENING AND ACTING

We will continue to respectfully review the state’s proposals (and raise questions when items need review or clarification.)

If you have information / resources / insights to contribute, for preserving this important civic building by Paul Rudolph, please let us know at:

office@paulrudolphheritagefoundation.org

Even with a few signs of a coming Fall, the center plaza’s oasis is still very green! Photo © the estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

S.O.S. Update # 2 : Proposed Demo & Development at Rudolph's Boston Government Service Center

For context, it may be useful to look at the overall plan of Boston’s Government Center area, which was laid out by I.M. Pei. There are several prominent buildings in the area, which were all built as part of the development of this center. The large rectangular building (near the center of this drawing) is the Boston City Hall (by Kalllmann, McKinnell & Knowles). The large, gently curving building to its left is Center Plaza (built as offices and ground-floor retail) designed by Welton Becket. Rudolph’s Government Service Center follows the perimeter of the triangular site at the map’s upper-left. About equidistant between the City Hall and the Government Service Canter are the two towers (shown as offset rectangles) of the John F. Kennedy Federal Building by Walter Gropius and The Architects Collaborative. Quincy Market, the celebrated food marketplace, is the long, horizontal, dark rectangle at the far right. It was designed by Alexander Parris and built in the early 19th Century.

Here’s a satellite view of the same area as shown in the drawing at the top of this post (and shown at approximately the same scale.) If you look at the drawing above, the entire site for Government Service Center was to be utilized for its building (plus the outdoor plazas, also designed by Rudolph)—and there was to be a tower in the center. In the photo above, one can see that the tower was not built, and the right-hand side of the site is now occupied by a wedge-shaped structure which was constructed later: it’s a municipal courthouse building, designed by another firm. Image courtesy of Google: Imagery ©2019 Google, Imagery

As we mentioned in our last update on this developing story, the State of Massachusetts’ Division of Capital Asset Management & Maintenance has issued a power point deck about the redevelopment proposal. In our last posting, we looked at their first slide: “Hurley Building at a Crossroads” (which was about the current condition and challenges of the building)—and offered our sincere questions and concerns.

Now it’s time to go a bit deeper into the deck, and consider the state’s further assertions and proposals. Let’s look at the next two:

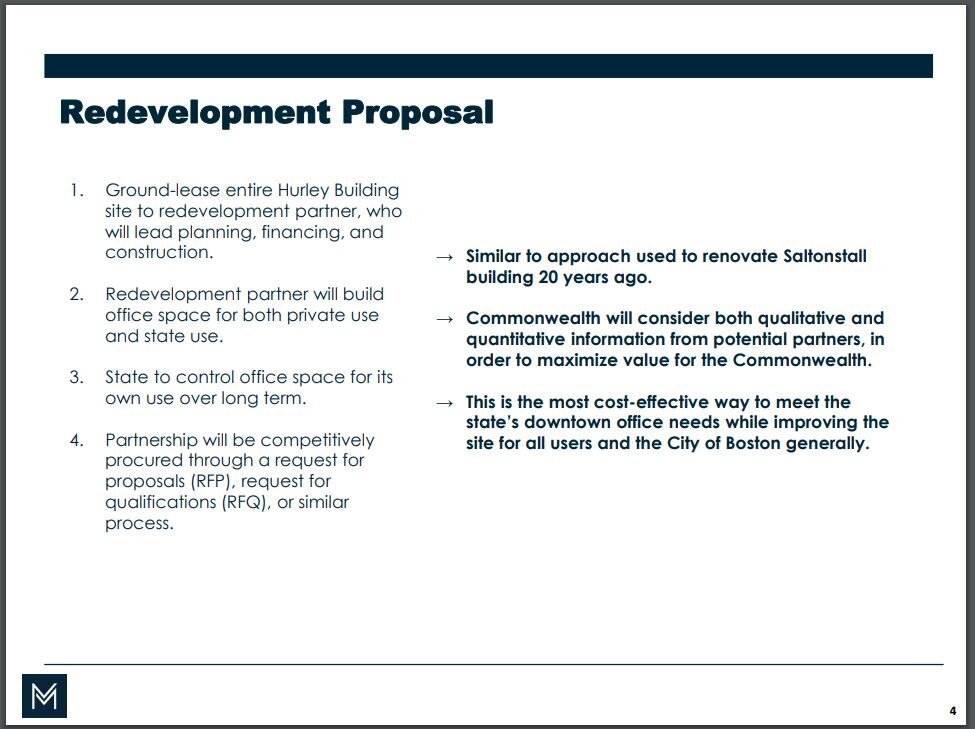

REDEVELOPMENT PROPOSAL

Following each of the slide’s points, we offer responses/questions:

Ground-lease entire Hurley Building site to redevelopment partner, who will lead planning, financing, and construction.

Shouldn’t there be a wider array of input from the beginning, to achieve good, public-spirited design? That would be lost if the development process is walled-off at its beginning—only soliciting public input later, (after the parameters seem to have been set). Without getting public input early it, it can lead to less-than-optimal results for the state and its citizens.

Redevelopment partner will build office space for both private use and state use.

It would be useful to know how the ratio determined?

State to control office space for its own use over long term.

It is important that the definition of “long term” be made explicit. If there’s a termination date to that agreement, then—at that end-date—how are disruptions to be avoided? Conversely: the state already owns the site—so, as long as they are their own tenant, there’s no need to worry about end-dates.

Partnership will be competitively procured through a request for proposals (RFP), request for qualifications (RFQ), or similar

It’s important to keep in mind that the overall proposal requires turning public space and buildings over to private use. Occasionally this can be done as a win-win situation, but it depends on many factors—and one of them is the quality and track-record of the development partner. So a key question is: Will the qualifications examine whether the developer has a real record of tangibly “giving back” (through the quality of what they build/plan)?

Similar to approach used to renovate Saltonstall building 20 years ago.

It would clarify things if we were told by what set of standards that success was judged—and how that was measured, and how far the project went to fulfill that.

Commonwealth will consider both qualitative and quantitative information from potential partners, in order to maximize value for the Commonwealth.

It would be useful to all parties if the above terms could be clarified—particularly the qualitative aspect.

This is the most cost-effective way to meet the state’s downtown office needs while improving the site for all users and the City of Boston generally.

Much is condensed into this one sentence. Implicit are assertions about: cost-effectiveness, state needs, the nature of the improvements, and who the users are. These would each need careful definition and review.

Lets consider the next slide:

EXPECTED BENEFITS

Following each of this slide’s points, we offer our responses/questions:

New, modern office space for state employees for same or less cost than comparable space elsewhere.

Renovation can usually yield modernization as comparable/less cost---if done efficiently. Moreover, renovation is almost always the greener alternative.

Long-term cost stability for both capital and operating budgets.

It would be good to know what this is this being compared to.

Improved public realm across 8-acre block. Increased site utilization and activation.

There’s abundant knowledge, from today’s public space designers, about making plazas and public spaces more alive and used—and many good case-studies of success. Don’t destroy what we have—but, instead, use that knowledge to make these unique spaces more alive to the public.

Economic benefits from large-scale development (jobs, tax revenue, etc.).

What’s often missing from balance-sheet are the costs of over-(“large scale”) development: especially overburdening the already under-pressure transit system and city services. Jobs will also be created through the modernization of the existing building.

NEXT STEPS

We’ll continue to respectfully review the state’s proposals—and raise questions when items need review an clarification.

If you have information or resources to contribute to preserving this important building by Paul Rudolph, please let us know at:

office@paulrudolphheritagefoundation.org

The overall design for the Boston Government Service Center. Although it is the work of a team of archiects, the design leader was Paul Rudolph-and it is truly his conception. This axonometric drawing shows his original full design for the complex—including public plazas in the center and at the three corners. In the middle was to be a tower with a “pinwheel”-shaped plan (in this drawing only the first few floors of it are shown.) © The Paul Rudolph estate, Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

S.O.S. - Boston Government Center Update: Considering the Development Proposal's Assessment of Rudolph's Building

The Seagram Building - by Rudolph?

The Seagram Building in New York City, under construction, designed by Mies van der Rohe. Photo: ReseachGate, Hunt, 1958

Mies van der Rohe’s Seagram Building is one of the loftiest of the high icons of Modernism. For decades, it was almost a sacred object. Indeed, several of his buildings - the Barcelona Pavilion and the Farnsworth House (as well as the Seagram) - were maintained in a bubble of architectural adoration.

Is reverence for Mies going too far? Actually, it’s architect Craig Ellwood at Mies van der Rohe’s National Gallery museum building in Berlin (caught while photographing a sculpture.) Photo: Architectural Forum, November 1968

SEEMS INEVITABLE

Mies is considered to be one of the triad of architects (with Wright and Corb) who were the makers of Modern architecture - a holy trinity! Given Mies’ fame - and the quietly assured, elegantly tailored, serenely-strong presence of Seagram (much like Mies himself) - it seems completely inevitable that he would be its architect. Like an inescapable manifestation of the Zeitgeist, it is hard to conceive that there might have been an alternative to Mies being Seagram’s architect.

Mies is watching! Photo: The Charnel House – www.charnelhouse.org

BUT WAS IT?

In retrospect, seeing the full arc of Mies’ career and reputation, it does seem inevitable. Whom else could deliver such a project? A bronze immensity, planned, detailed and constructed with the care of a jeweler.

But - as usual - the historical truth is more complex and messy (and more interesting).

GETTING ON THE LIST(S)

Several times, Phyllis Lambert has addressed the history of the Seagram Building and her key role in its formation. But the story is conveyed most articulately and fully in her book, Building Seagram—a richly-told & illustrated, first-person account of the making of the this icon, published by Yale University Press.

Phyllis Lambert’s fascinating book on the creation and construction of the Seagram Building. Image: Yale University Press

Part of the story is her search for who would be the right architect for the building. In one of the book’s most fascinating passages, she recounts the lists that were made of prospective architects:

“In the early days of my search, I met Eero Saarinen at Philip Johnson’s Glass House in Connecticut. In inveterate list-maker, he was most helpful in proposing what we draw up a list of architects according to three categories: those who could but shouldn’t, those who should but couldn’t, and those who could and should. Those who could but shouldn’t were on Bankers Trust Company list of February 1952, including the unimaginative Harrison & Abramovitz and the work of Skidmore , Owings & Merrill, which Johnson and Saarinen considered to be an uninspired reprise of the Bauhaus. Those who should but couldn’t were the younger architects, none of whom had worked on large buildings: Marcel Breuer, who had taught at the Bauhaus and then immigrated to the United States to teach with Gropius at Harvard, and, as already noted, had completed Sarah Lawrence College Art Center in Bronxville; Paul Rudolph, who had received the AIA Award of Merit in 1950 for his Healy Beach Cottage in Sarasota, Florida; Minoru Yamasaki, whose first major public building , the thin-shell vaulted-roof passenger terminal at Lambert-Saint Louis International Airport, was completed in 1956; and I. M. Pei, who had worked with Breuer and Gropius at Harvard and became developer William Zeckendorf’s captive architect. Pei’s intricate, plaid-patterned curtain wall for Denver’s first skyscraper at Mile High Center was then under construction.

The list of those who could and should was short: Le Corbusier and Mies were the only real contenders. Wright was there-but-not-there: he belonged to another world. By reputation, founder and architect of the Bauhaus Walter Gropius should have been on this list, but in design, he always relied on others, and his recent Harvard Graduate Center was less than convincing. Unnamed at that meeting were Saarinen and Johnson themselves, who essentially belonged to the “could but shouldn’t” category.”

WHAT IF’S

So Rudolph was on the list and considered, if briefly. Even that’s something—a real acknowledgment of his up-and-coming talent.

Moreover, Paul Rudolph did have towering aspirations. In Timothy Rohan’s magisterial study of Rudolph (also published by Yale University Press) he writes:

“Rudolph had great expectations when he resigned from Yale and moved to New York in 1965. He told friends and students that he was at last going to become a ‘skyscraper architect,’ a life-long dream.”

That relocation, from New Haven to New York City, took place in the middle of the 1960’s—about a decade after Mies started work on Seagram. But, back about the time that Mies commenced his project, Rudolph also entered into his own skyscraper project: the Blue Cross / Blue Shield Building in Boston.

Paul Rudolph’s first large office building, a 12 storey tower he designed for Blue Cross/Blue Shield from 1957-1960. It is located at 133 Federal Street in Boston. Photo: Campaignoutsider.com

It takes a very different approach to skyscraper design, particularly with regard to the perimeter wall: Rudolph’s design is highly articulated, what Timothy Rohan calls a “challenge” to the curtain wall (of the type with which Mies is associated)—indeed, “muscular” would be an appropriate characterization. Moreover, Rudolph integrated mechanical systems into the wall system in an innovative way.

A closer view of the Blue Cross/Blue Shield’s highly articulated façade and corner, seen nearer to street-level. Photo: Courtesy of the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth Library

And, Rudolph did end up fulfilling his post-Yale desire to become a “skyscraper architect”—at least in part. He ended up doing significantly large office buildings and apartment towers: in Fort Worth, Hong Kong, Japan, Singapore, and Jakarta. Each project showed him able to work with a variety of skyscraper wall-types, materials, and formal vocabularies. Rudolph, while maintaining the integrity of his architectural visions, also could be versatile.

And yet -

He was on that Seagram list, and we are left with some tantalizing “What if’s…

What if he had gotten the commission for Seagram—an what would he have done with it?