Ernst Wagner, visiting a recreation of one of the most famous works from the first phase of Paul Rudolph’s career: the Walker Guest House (Sanibel Island, Florida, 1952) It was on-view (and visitable) during a festival celebrating Modern architecture in Palm Springs, California that Mr. Wagner attended. The home was fitted-out with furniture and objects of the period—including a gooseneck table lamp and a “classic” Olivetti Lettera portable typewriter. Photograph by Kelvin Dickinson © The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

Ernst Wagner: A Friend And Supporter During Rudolph’s Lifetime—And Beyond

We want to introduce you to someone who is important to Rudolph’s work and reputation: Ernst Wagner - a dedicated friend and colleague of Rudolph, and the original founder of two foundations whose aim has been to protect and raise awareness about the importance of Paul Rudolph’s cultural legacy.

Rudolph was a Success—so Why the Need to Protect his Work?

Before we get to know Ernst (and why he’s worked so hard on Rudolph’s behalf), we need to explain why Paul Rudolph—who had been at the summit of success and fame in the world of Architecture—needs protection or profile-raising at all.

What’s the value of a reputation? (especially Rudolph’s)

If it’s a good one, it means that you’re taken seriously: what you say or do influences how others think and live and work. You “have a vote”—and maybe even a powerful, persuasive voice. Others—citizens or colleagues or students—are inspired by you, or even attempt to model their behavior (or careers) after yours.

Starting in the mid-1950’s, and for nearly two decades, Paul Rudolph was seen by the architectural profession as such a model: manifesting an energy, prolific creativity, and dedication of the kind and level to which colleagues and students aspired. As his former student & employee (and long-time friend) Stanley Tigerman put it:

“For Paul Rudolph, architecture and life were inextricably intertwined. He lived, breathed, slept, lectured, taught, and of course practiced architecture. I was thoroughly bedazzled by the depth of his commitment to unpacking the never-ending layers of space and mass that architecture represented for him. He was, other than simply being a superb teacher, the consummate architect, if by that one means a person who, in a Zen-like sense “became” his work. In all these years of practicing the discipline, if there was anyone I met who “walked the walk” it was Paul Marvin Rudolph.”

Vincent Scully (at far left) and Paul Rudolph (at far right, with arms crossed), observing Yale student Stanley Tigerman present his design project. Photograph from the archives of the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

Rudolph’s Professional Arc

In that period, Rudolph was described as “the next Frank Lloyd Wright” - and if he was “up-and-coming” in the mid-1950’s, by the time he’d completed his Yale Art & Architecture building (in 1963) he was becoming nationally and then world-famous. Leading Yale’s school of architecture, teaching in it, and running his practice would have broken most people - especially as his office was busy with a seemingly endless stream of significant commission for governmental, educational, religious, residential and commercial clients.

Project lists for Paul Rudolph show well over 300 commissions, and the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation’s website has a “project page” for each of them. This is a screen shot from just a portion of the website’s grid of Rudolph’s 1960’s projects, indicating the range of work he was doing during the period of his greatest fame—including commissions for governmental, educational, residential, and commercial clients.

At the height of this success (and after a good long run as the chair of Yale’s School of Architecture, from 1958-to-1965), Rudolph resettled in New York City, anticipating a continuation of this professional pace, and to garner even larger commissions—a not-unreasonable expectation, given his rise, track-record, and abilities…

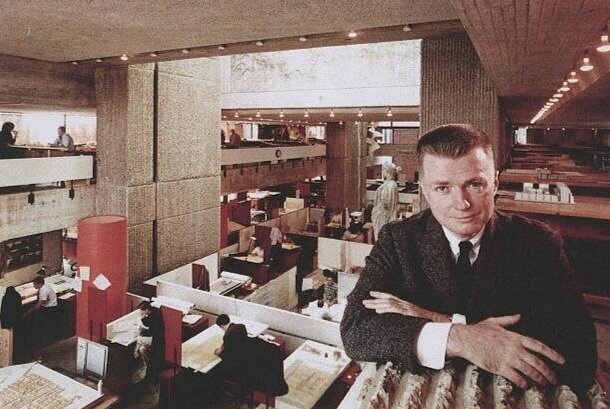

Rudolph photographed at the height of his fame and professional success, seen here in his recently opened Yale Art & Architecture Building in New Haven, Connecticut - a time when he was simultaneously the head of the school, teaching, and running a busy architectural practice.

But it was not to to be.

Rather than being commissioned for an ever-rising tide of ever greater projects, a combination of factors led to the diminishment of his practice. The causes can be debated, but among the factors cited are:

the change (and elimination) of government funding for the type of large, civic projects he had been getting

a possible “tarnishing” of his reputation because of a devastating fire at the Yale Art & Architecture Building—his most famous commission—even though Rudolph had been away from Yale for several years by then

a general counter-cultural push-back against authority (and it’s symbols, like the kind of buildings that Rudolph was associated with)

the arrival of Post-Modernism as the new, dominant style—as practiced by architects and preached and taught in academia: a style both eschewing (and eschewed by) Paul Rudolph.

finally, his own former students, the next generation of architects (who were seen as the new up-and-comers), publicly disparaged their own former teacher as no longer being relevant (or worse)—an example of what Alan Forrest called “the assassination mentality”: an ever-recurrent syndrome wherein the new generation feels the need to kill off its predecessors.

Clearly, none of the above was in Rudolph’s control or his responsibility—but he was subject to these powerful cultural phenomena all-the same, and his practice suffered accordingly.

That was not the last word on Rudolph—and there was a happy ending. Later, he did enjoy a measure of success (if not recognition): in the final phase of his career he was engaged by enthusiastic clients to work on large and significant projects in Hong Kong, Jakarta, and Singapore—but he had to travel to the other side of the globe to work on those commissions.

With his decades of achievements, it always bothered Rudolph that Pritzker Prize juries never chose him, nor was he ever given the AIA Gold Medal - and he was met by the indifference (if not hostility) of his colleagues at home. In Rudolph’s time—the era before the internet—the way an architect’s presence was felt in the profession was through being published—either in magazines or books—and Rudolph was largely excluded from those forums. One former Rudolph staff member told us that, when he was looking for a job and an employment agency suggested working for Rudolph, he thought “Rudolph? Isn’t he dead?”

Paul Rudolph was very much alive, but had utterly dropped off the profession’s radar.

A Prediction

Wright is a huge figure now—and he’s made his way into the popular conscience so much that even novels get written about him. But Wright (and his reputation) also suffered ups-and-downs through his long career—and afterward. Philip Johnson gave Wright the most backhanded of compliments by calling [dismissing?] him as “the greatest architect of the 19th century,” and some of his finest buildings were demolished—the Larkin Building and the Imperial Hotel being outstanding examples. Such a fate is unthinkable today—but it took decades for Wright’s work to achieve such a status.

A vintage postcard showing an interior of the Frank Lloyd Wright’s Imperial Hotel in Tokyo. One can get an idea of the scale by looking at the chairs in the lower-right corner. Bruce Goff said that, in this building complex, Wright reached a high-point of compositional richness which he was never to achieve again—yet the building lasted only 44 years before being demolished after it closed in 1967. Today such a building would be regarded as a national—indeed, international—treasure. But Wright’s reputation, at the time of this building’s destruction, was not what it became in subsequent decades.

Ernst Wagner tells us that Rudolph thought he’d have a reputation similar to Wright’s: famous as a young architect; then a long valley in his middle years, then a peak towards the end—and that seems to have been borne out to a large degree. But the late “peak” was his work in Asia, and those large commissions and extensive activity remained largely unknown to the Western architectural community.

Ernst Wagner: Friend and Colleague of Rudolph

Ernst Wagner is a Swiss citizen, who visited the US in the late 60’s, ultimately living and working here ever since. He became a friend of Rudolph, and later a business partner—and together they engaged in several projects:

They co-founded the innovative Modulightor lighting company in the mid-1970’s.

Ernst supported (and helped) when Rudolph was contemplating purchasing 23 Beekman Place (which was transformed into become Rudolph’s famous “Quadruplex” residence.).

They collaborated on creating the Modulightor Building—a multi-purpose structure that functioned both as a headquarters for the growing lighting firm, as well as the location of Rudolph’s architectural practice.

A vintage business card, from the archives of the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation, showing that Ernst Wagner was once considered part of Paul Rudolph’s organization. © The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

Ernst Wagner worked with Rudolph on these ventures, and the archives of the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation document Ernst’s involvement in all aspects of them. Even after the lighting company was up-and-running, and the building substantially complete, Ernst Wagner continued to work closely with Paul Rudolph—and their friendship extended to Ernst’s caring for Rudolph through his final illness from mesothelioma, and passing in 1997.

Putting Rudolph “Back On The Shelf”

Ernst Wagner was the primary heir of Paul Rudolph, and executor of Rudolph’s estate. Feeling an immense gratitude to his late friend and colleague, he was determined to honor him—and that meant protecting his legacy and bringing Paul Rudolph back into the consciousness of the architectural world.

Although Ernst is fluent in English, he sometimes peppers Swiss phrases into his speaking and writing—and one of the most vivid is when he says that he wants to “put Rudolph back on the shelf”—a Swissism for bringing something forward and into prominent view. He is determined to do this for Rudolph.

To that end Ernst Wagner has been very active:

He founded and financially underwrote two organizations: the Paul Rudolph Foundation in 2002; and later the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation in 2015

He was the chief sponsor and donor for two exhibits which celebrated Paul Rudolph’s centenary in 2018.

Not only did he give extensive financial support (and lent materials) for the centenary exhibits, but he also provided exhibit space for one of them - and continues open that space for the ongoing display of portions of those exhibitions

The Modulightor Building had been left unfinished at Rudolph’s passing. Since then—using architectural documents left by Rudolph and in collaboration with an architect who’d worked with Rudolph—he’s completed the building as Rudolph wished to do while he was alive.

He makes the Modulightor Building available for tours by schools from around the world, and classes of students in architecture, interior design, lighting design, architectural history, and design media are received throughout the year. Architectural historians are also drawn to study the building, and their visits are welcomed.

He opens the Modulightor Building for a monthly “Open House”—thus allowing others to experience a Rudolph-designed environment first hand.

Within the Modulightor Building is a Rudolph-designed duplex residence, furnished with many of the objects and books which Mr. Wagner inherited from him as well as objects they collected on their travels around the world together. It is very hard to obtain access to any Rudolph interior—and even harder when it is occupied—yet Ernst welcomes those interested in Rudolph’s work into his own home, and over the years he has allowed thousands to view these spectacular private spaces.

He provides space and resources for the offices and archives of the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

He serves on the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation’s board, and represents it at architectural events (like the 2018 Sarasota Architectural Foundation’s “Sarasota Mod” convention.)

During the Paul Rudolph centenary celebrations and exhibitions in 2018, a variety of events were held. On this occasion one can see several of the speakers: from left-to-right: Carl Abbot, Kelvin Dickinson, and Ernst Wagner.

To give a vivid sense of Paul Rudolph, two of the items on view during his centenary year exhibitions were this tweed jacket and knit tie—both of which had been owned and worn by the architect. Such tweed attire and knit neckwear were a frequent part of American architects’ image during the high-point of Rudolph’s career in the 50’s and 60’s—and the exhibit curators were grateful for these examples lent by Mr. Wagner.

Ernst Wagner with R.D. Chin. Mr. Chin is an architect who worked closely with Paul Rudolph. He was featured as the first speaker in the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation’s “Salon” lecture series, and generously donated Rudolph material to the foundation archives. Photograph by Kelvin Dickinson © The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.

The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation is grateful to Ernst Wagner for his ongoing dedication to putting Paul Rudolph “on the shelf” again!

A snapshot of Paul Rudolph (left), Ernst Wagner (right), and their close friend Emily Sherman (center) during a trip to Europe.