Why Classical Architecture Still Matters to Modern Design (and What Paul Rudolph Understood)

Modern architecture is often framed as a clean break from the past: new materials, new programs, new cities, new ways of living. But the most enduring modern work rarely comes from amnesia. It comes from selective memory—an ability to translate what classical and traditional architecture does well into forms that belong unmistakably to their own time.

Paul Rudolph is a useful guide here, not because he copied historical styles (he didn’t), but because his work shows how modern architecture can regain what tradition has always offered: legibility, civic presence, and the power to communicate shared values.

Tradition isn’t a style. It’s a set of tested design intelligences.

When people say “classical” or “traditional,” they often mean columns, cornices, and symmetry. But the deeper value is the discipline behind those forms:

Proportion and hierarchy (what matters most is made most visible)

Sequence and procession (how a building is experienced over time)

Urban responsibility (how a facade contributes to a street, a campus, a public life)

Material clarity (what something is made of, and how it’s put together)

These aren’t nostalgic preferences. They’re practical tools for making buildings that are readable, humane, and durable—culturally as well as physically.

Rudolph’s modernism was never “anti-context.”

Rudolph’s career is often associated with the muscular confidence of mid-century modernism, but he was not interested in modern architecture as a universal, placeless language. He repeatedly treated the city and the existing fabric as design partners.

In discussing Rudolph’s work, architect George Ranalli points to Rudolph’s “strong interest in making a positive contribution to an existing neo-Gothic situation without forgoing the integrity of Modern architectural design.” That’s a concise description of what the best tradition-minded modernism does: it respects what’s already there, without resorting to imitation.

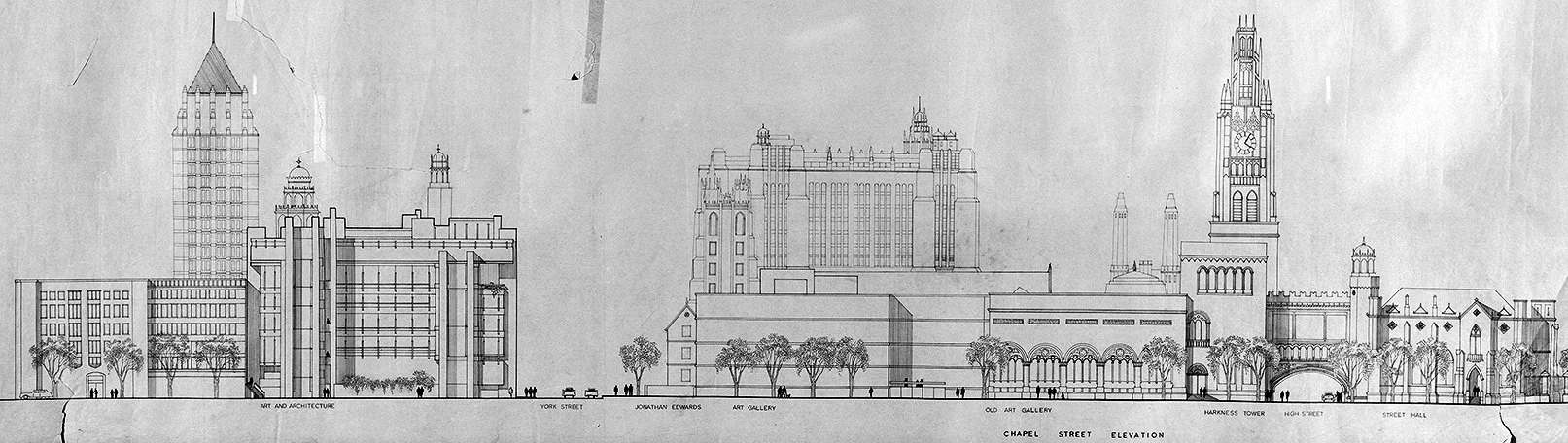

Rudolph’s drawing of the Art & Architecture building in the context of the existing Yale campus.

At Yale, Rudolph’s Art and Architecture Building (Rudolph Hall) is often discussed through the lens of style—Brutalism, monumentality, controversy. But the more interesting question is classical in spirit: what role does a building play in the civic and educational life around it?

Architecture’s job is to communicate—something tradition has always understood.

Classical architecture has always been comfortable with the idea that buildings mean something: they symbolize institutions, express public values, and create shared reference points.

That idea is not incompatible with modern architecture. In fact, it’s essential to it.

Ranalli writes that “Architectural design has many purposes, one of which is to communicate ideas.” That’s a statement modernists and classicists can both agree on. The difference is that tradition tends to come with a well-developed vocabulary for communication—how to make entrances obvious, how to signal importance, how to shape public space.

Rudolph’s work, at its best, expands modern architecture’s communicative range. It insists that modern buildings can be more than efficient containers or abstract objects. They can be civic actors.

Monumentality isn’t the enemy of modern life—it’s part of it.

One of the quiet gifts of classical architecture is its comfort with monumentality: not bigness for its own sake, but the ability to give form to collective aspiration.

Rudolph understood this, even when the cultural mood turned against it. He pursued buildings that could hold complexity and contradiction—private and public, intimate and grand—without collapsing into either bland neutrality or theatrical pastiche.

And crucially, the “monument” in modern architecture doesn’t need classical ornament to be classical in purpose. It needs:

A clear relationship to the city

A legible structure of parts

A sense of permanence and public meaning

That’s why tradition still matters: it keeps modern architecture from shrinking into mere image-making.

The real lesson: modern architecture needs continuity to stay human.

The strongest argument for classical and traditional architecture today isn’t that we should rewind design history. It’s that modern architecture performs better—socially, emotionally, civically—when it reclaims the underlying principles tradition refined over centuries.

Rudolph’s legacy shows a path forward:

Honor context without imitation

Use modern means to achieve timeless ends (clarity, dignity, delight)

Treat architecture as a public language—not just a private aesthetic

Or, to return to the point that bridges both worlds: architecture communicates. Tradition gives us a long-tested grammar. Modern architecture gives us new materials and new sentences. The future belongs to designers who can do both.

If you want to see this conversation in real space

The Paul Rudolph Institute for Modern Architecture preserves and activates the legacy of modern architects whose work continues to shape how we think about cities, buildings, and public life—through exhibitions, open houses, and educational programming in the only Paul Rudolph-designed space in New York City open to the public.

Interested in supporting the work? Become a member, attend an open house, or follow along for more archive discoveries and preservation spotlights.