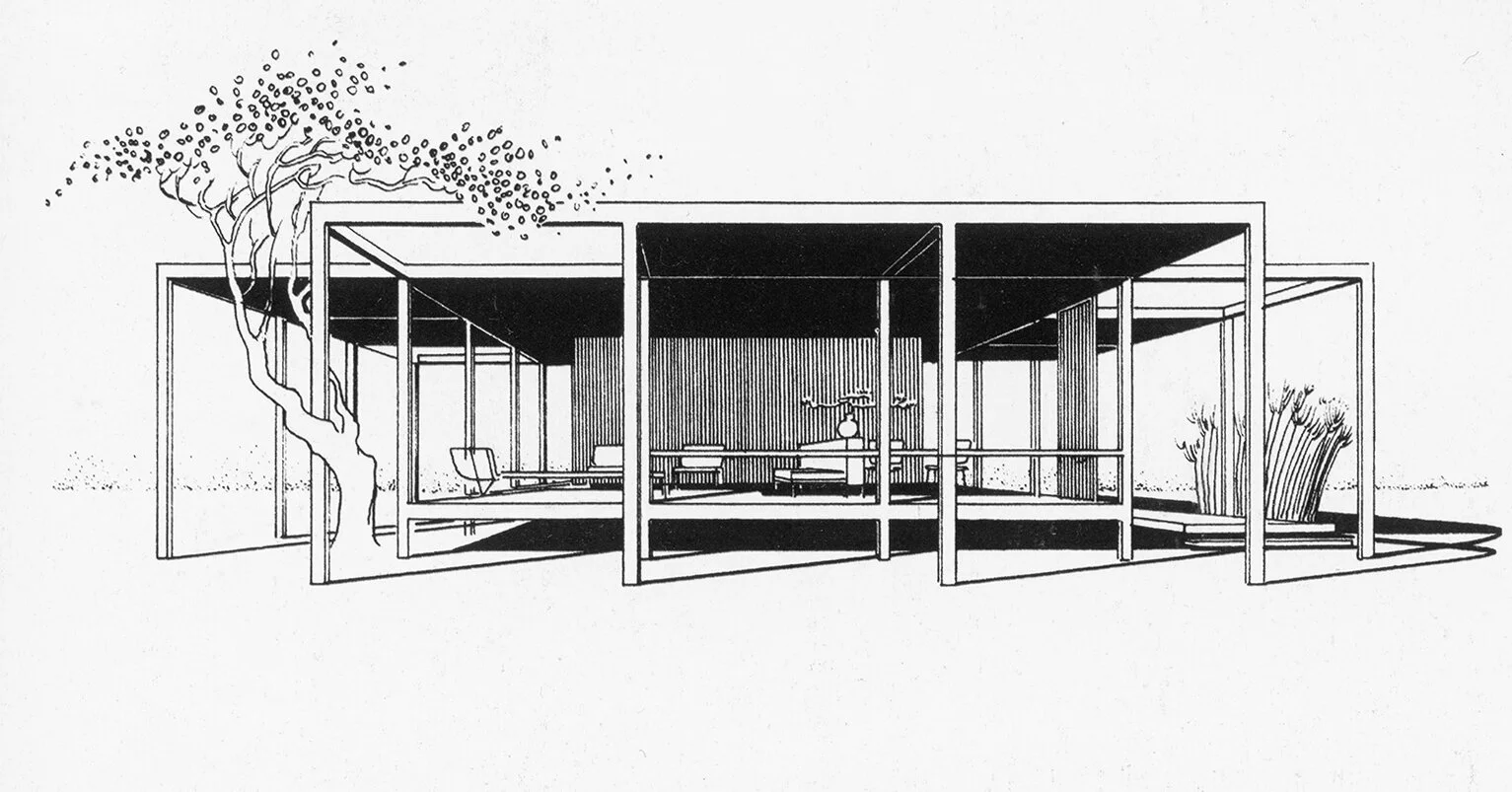

Paul Rudolph’s drawings of his Walker Guest House in Florida, showing how the exterior flaps work. Located on all four sides of the house, they open and close (and can be set at almost any angle), which allows for flexibility in dealing with changes in sun, wind, and rain (and desire for privacy). Moreover, they operate with a simple pulley-and-counterweight system, so their adjustment consumes no fossil fuel. This is “green design”—before the term was even invented. © The estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

Rudolph’s Engagement

In a half-century career, Rudolph was engaged with over 300 projects (dealing with every different building type, range of functions, material, budget, and environment). Add to that his engagement with teaching, writing, lecturing, construction, business, and interior/furniture/lighting design…—it’s no wonder that one can study him via the multiple roles he played: as a designer and artist of form & space, as an urbanist, as a builder, as a navigator in the world of clients, as an experimenter with materials and systems, as a role-model, as a philosopher of design, as an educator and mentor….

But as a “green” architect?

That characterization has largely not been connected with Rudolph. Perhaps that’s because he belonged to the generation of Modern architects who matured in the Mid-century era of plentiful and inexpensive energy—well before the ecology/environmental movement became part of public (and professional) consciousness. [For context: the first Earth Day was celebrated in 1970—seven years after the completion of Rudolph’s Yale Art & Architecture Building.]

Buildings from that era were still built with single-glazing and moderate amounts of insulation—and notions of “embodied energy,” lifetime energy costing, and energy recovery were hardly considered (if thought of at all) in standard architectural practice. It took a long time for ecological considerations to get into the thought-patterns of architects, and it took an international emergency (the 1973 oil crisis) to really have minimizing energy use even begin to be taken seriously.

Up until that change in thinking, rectilinear glazed boxes—in every height and proportion, from single-storey pavilions-to-skyscrapers—were the preponderant product of post-war mainstream architectural practice. [Sometimes that recurrent form is referred to as the “Harvard Box”, because the Gropius-educated architects emerging from his architecture program (and those widely influenced by that philosophy) seemed to offer a box—more-or-less glazed—for every architectural challenge.]

Mies van der Rohe’s Crown Hall building in Chicago, the home of Illinois Institute of Technology’s school of architecture. The glazing system (and the architecture of which it is a part) hardly varies on the four sides of the building—even though solar loads have considerable variation on each face. Constructed during the first half of the 1950’s, Crown Hall became a significant example of the International Style—and was created in an era when energy usage was not a prime consideration in designs of mainstream architects. Energy became more of a priority in subsequent decades and into the next century—and a determinant of architectural form. Photo by Arturo Duarte Jr., courtesy of Wikimedia.

But such limited thinking was not for Rudolph (who was, incidentally, a graduate of Gropius’ Harvard program!) There’s evidence that he—like one of his great heroes, Wright—had an abundant awareness of energy. This was particularly in the domain of taking into account sun loads, and the path of the sun over the course of a day, and in different seasons. Rudolph designed to accommodate and handle those factors.

A vintage postcard from Florida—a state self-identifying with sunshine.

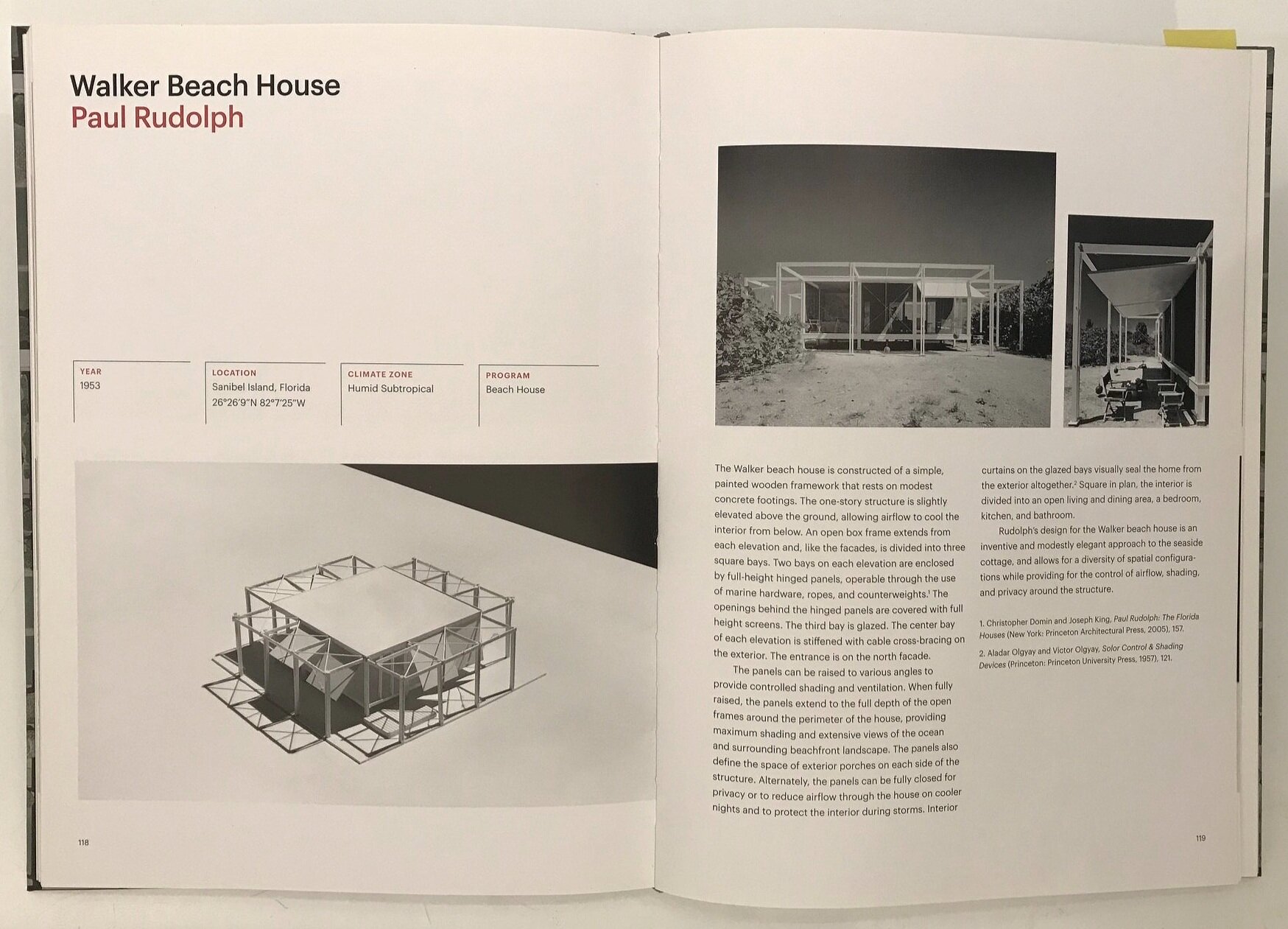

Since Rudolph’s career gets started in Florida—the American state so explicitly associated with sunshine—one could imagine that the intense level of sun-load itself argued for inventive architectural solutions. Examples of Rudolph meeting that challenge are included in a book which focuses on how some Modern architects did address environmental issues (at least in some of their projects): Lessons from Modernism. Deeply researched, it presents numerous case studies—including works by Wright, Albert Frey, Aalto, Niemeyer, Xenakis, Prouve, and others. Rudolph is represented by two of his houses in Florida: the Walker Guest House, and the Healy “Cocoon” Guest House, and solar plot studies are presented for each.

Lessons from Modernism, edited by architect and educator Kevin Bone, looks to the history of Modern architecture (in the middle two quarters of the 20th Century) to see how some architects did focus on environmental concerns. Two of Paul Rudolph’s houses, (from the initial phase of his career, in Florida) are analyzed in the book.

An example of the case studies in Lessons from Modernism: a spread from the book’s section on the Walker Guest House. Eduardo Alfonso, the curator of the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation’s 2018 centenary exhibition on Rudolph, participated in this study.

The analysis of the Walker Guest House, presented in the book, included sun plot studies.

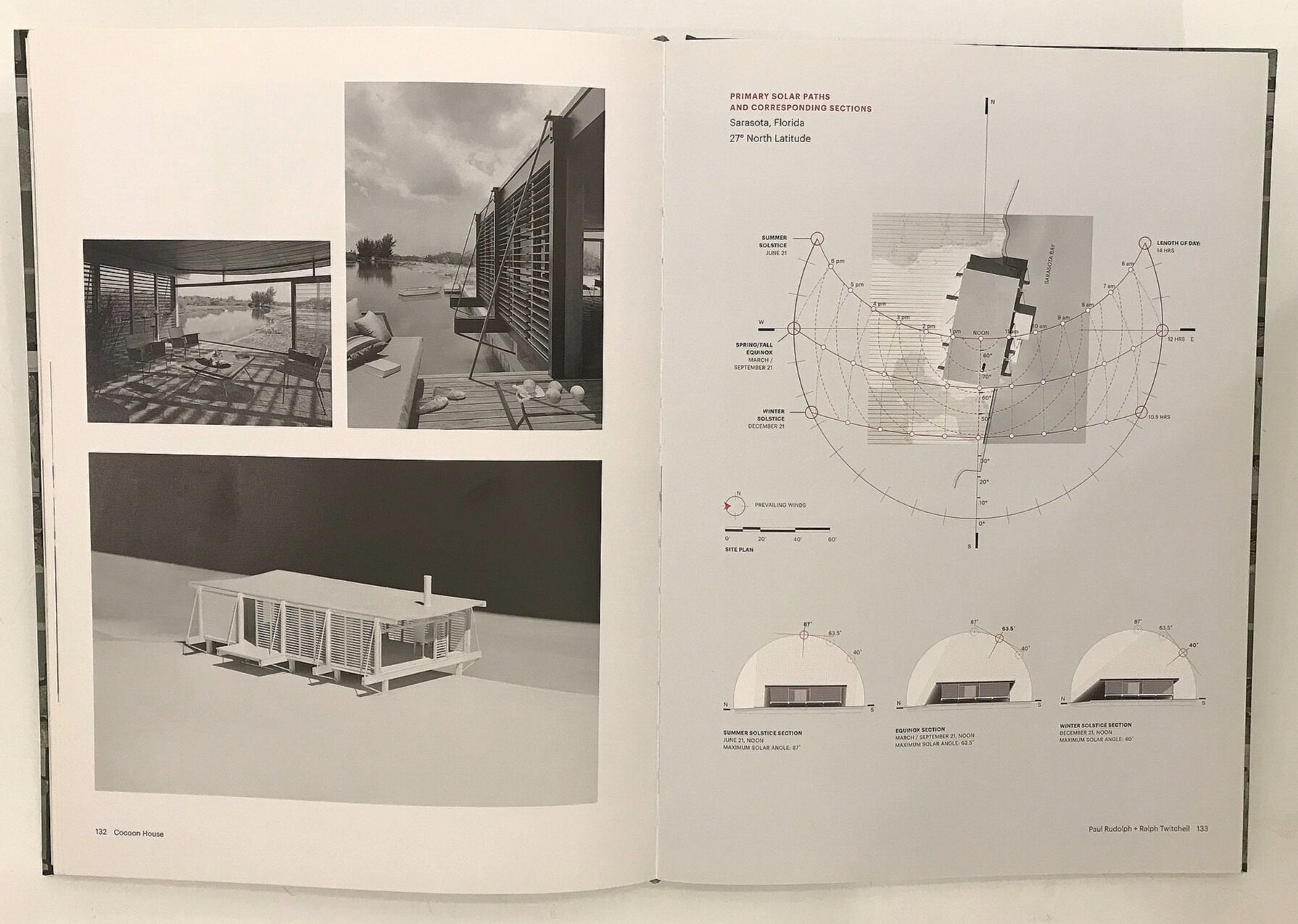

The Healy (“Cocoon”) Guest House is the other Rudolph-designed house which is analyzed in the book.

As with the other case studies in the book, a sun path analysis was made for Rudolph’s Healy (“Cocoon”) house design.

Other buildings by Paul Rudolph show inventive ways of addressing sun loads—and we’ll illustrate those in a later post (“Part Two”) on this topic.

Meanwhile: readers might want to explore Rudolph numerous projects, to discover his inventiveness in this domain. His over 300 commissions can be seen in the “Projects” section of the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation website.